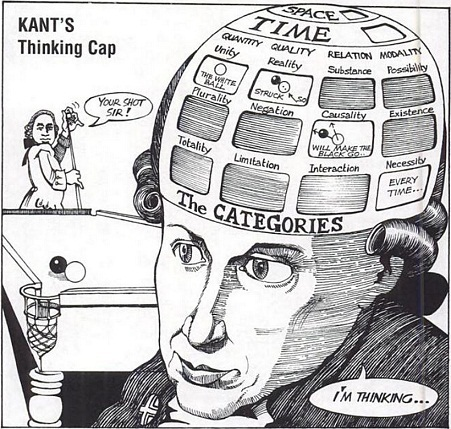

In Kant’s terms, the “subjective framework,” that makes perception possible, is the whole a priori structure of our mind (forms of intuition plus categories). “Space” and “time” are pure, a priori forms of human sensibility—ways in which any sensible object must be given to us. And, “Categories” are the pure concepts of the understanding: basic a priori ways in which the mind must think any possible object of experience. They are not learned from experience but are conditions for having coherent experience at all.

SUBJECTIVE FRAMEWORK

The “subjective framework” is the set of a priori conditions that belong to our cognitive constitution:

- The pure forms of sensibility (space and time), which shape how anything can be given.

- The pure concepts of the understanding (categories), which structure how what is given can be thought as an object under concepts like substance, causality, unity, etc.

Calling this framework “subjective” does not mean arbitrary or merely personal; it means it belongs to the subject’s side and does not characterize things in themselves, yet it is necessary and universal for all human experience.

SPACE

For Kant, space is not a property of things in themselves or a general concept abstracted from experiences, but a single, pure intuition that structures all outer appearances. It is the form of outer sense: any object given as “outside” us must be represented as spatially ordered (having position, size, relations of beside/within, etc.), and this spatial framework is in the mind a priori, not learned from experience.

TIME

Time is likewise a pure intuition, but it is the form of inner sense: the way in which all our representations—inner states and, mediately, outer appearances—are ordered as earlier/later, simultaneous, enduring, etc. Time is not something we perceive as an object; rather, it is the universal temporal form to which all our experiences are subject and without which no succession or change could be represented at all.

CATEGORIES

Kant groups twelve categories under four headings, mirroring the forms of judgment:

- Quantity

- Unity: the concept under which an object is taken as one, a single something counted as a unit.

- Plurality: the concept under which there are several units, a “many” of the same sort.

- Totality: the concept of the all-of-them-taken-together, the completed whole of a plurality.

- Quality

- Reality: the pure concept of a positive determination of sensation (some degree of a feature, such as warmth or brightness), thought as something given.

- Negation: the pure concept of the absence of that determination, corresponding to a zero degree of the same scale (cold as absence of warmth, darkness as absence of light).

- Limitation: the concept of a positive reality bounded by negation, i.e., a finite degree of a sensible feature that is less than maximal but more than zero.

- Relation

- Inherence and Subsistence: the category under which something is thought as a substance that persists through time, with properties (accidents) that inhere in it and can change while the underlying subject remains.

- Causality and Dependence: the concept under which one state or event is thought as the cause that determines another as its effect in temporal succession.

- Community (Reciprocity): the concept of substances coexisting in space such that each stands in mutual causal interaction with the others, forming a network of reciprocal influence.

- Modality

- Possibility / Impossibility: concerns whether a concept agrees with the formal conditions of possible experience, that is, whether such an object could coherently appear in space and time under the categories.

- Existence (Actuality) / Non‑existence: concerns whether something is given in accordance with the conditions of experience, i.e., whether it is actually instantiated in perception.

- Necessity / Contingency: concerns whether, given the conditions of possible experience and lawful connection (e.g., causal laws), an object or state must be so, or could be otherwise.

The categories are rules for synthesizing the manifold of intuition into objects of experience: they determine, for example, that what is experienced endures as a substance, that changes stand in causal relations, and that objects can be judged possible, actual, or necessary. Without these a priori concepts, sensations would be a “blind” manifold, never rising to objective cognition; with them, appearances can be thought as objects in one unified experience.

.

Comments

Too much material is being sent out.

Our communication/ suggestions are being ignored.

We unsubscribed.

I am sorry to see you leave.