Reference: The Book of Physics

Note: The original text is provided below.

Previous / Next

Summary

Eddington is interpreting the electrical theory of matter to mean that the motion of the measuring equipment will result in Fitzgerald contraction and that would influence the measurements. He believes that this would occur even when no accelerations are involved. He, therefore, concludes that the Newtonian length of an object cannot be determined. And, therefore, the present-day physics is based on fictitious measurements. This has now resulted in the whole structure of classical physics tumbling down.

.

Comments

In truth, there are no problems in measurements unless very high accelerations are involved. But, in those cases, the resulting contractions can be calculated and corrections made.

.

Original Text

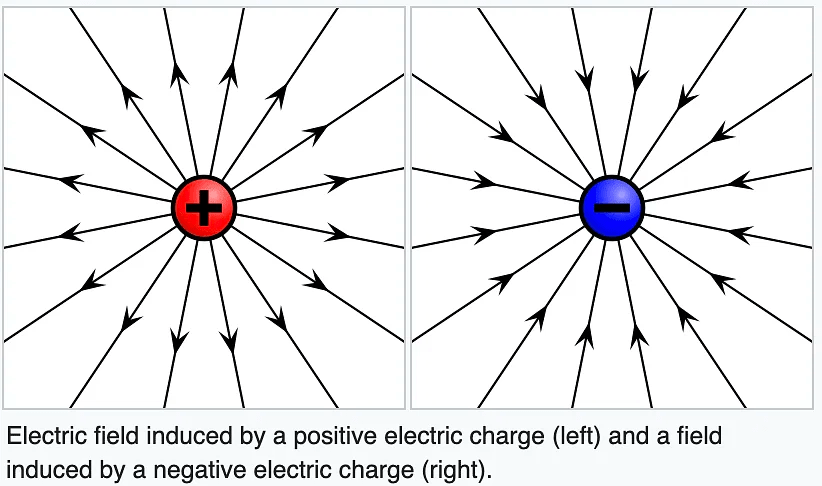

This thought will be followed up in the next chapter. Meanwhile let us glance back over the arguments that have led to the present situation. It arises from the failure of our much-trusted measuring scale, a failure which we can infer from strong experimental evidence or more simply as an inevitable consequence of accepting the electrical theory of matter. This unforeseen behaviour is a constant property of all kinds of matter and is even shared by optical and electrical measuring devices. Thus it is not betrayed by any kind of discrepancy in applying the usual methods of measurement. The discrepancy is revealed when we change the standard motion of the measuring appliances, e.g. when we compare lengths and distances as measured by terrestrial observers with those which would be measured by observers on a planet with different velocity. Provisionally we shall call the measured lengths which contain this discrepancy “fictitious lengths”.

According to the Newtonian scheme length is definite and unique; and each observer should apply corrections (dependent on his motion) to reduce his fictitious lengths to the unique Newtonian length. But to this there are two objections. The corrections to reduce to Newtonian length are indeterminate; we know the corrections necessary to reduce our own fictitious lengths to those measured by an observer with any other prescribed motion, but there is no criterion for deciding which system is the one intended in the Newtonian scheme. Secondly, the whole of present-day physics has been based on lengths measured by terrestrial observers without this correction, so that whilst its assertions ostensibly refer to Newtonian lengths they have actually been proved for fictitious lengths.

The FitzGerald contraction may seem a little thing to bring the whole structure of classical physics tumbling down. But few indeed are the experiments contributing to our scientific knowledge which would not be invalidated if our methods of measuring lengths were fundamentally unsound. We now find that there is no guarantee that they are not subject to a systematic kind of error. Worse still we do not know if the error occurs or not, and there is every reason to presume that it is impossible to know.

.