Reference: The Nature of the Physical World

This paper presents Chapter XIV (section 3) from the book THE NATURE OF THE PHYSICAL WORLD by A. S. EDDINGTON. The contents of this book are based on the lectures that Eddington delivered at the University of Edinburgh in January to March 1927.

The paragraphs of original material are accompanied by brief comments in color, based on the present understanding. Feedback on these comments is appreciated.

The heading below links to the original materials.

.

Let us examine a typical case of successful scientific prediction. A total eclipse of the sun visible in Cornwall is prophesied for 11 August 1999. It is generally supposed that this eclipse is already predetermined by the present configuration of the sun, earth and moon. I do not wish to arouse unnecessary misgiving as to whether the eclipse will come off. I expect it will; but let us examine the grounds of expectation. It is predicted as a consequence of the law of gravitation—a law which we found in chapter VII to be a mere truism. That does not diminish the value of the prediction; but it does suggest that we may not be able to pose as such marvellous prophets when we come up against laws which are not mere truisms. I might venture to predict that 2 + 2 will be equal to 4 even in 1999; but if this should prove correct it will not help to convince anyone that the universe (or, if you like, the human mind) is governed by laws of deterministic type. I suppose that in the most erratically governed world something can be predicted if truisms are not excluded.

But we have to look deeper than this. The law of gravitation is only a truism when regarded from a macroscopic point of view. It presupposes space, and measurement with gross material or optical arrangements. It cannot be refined to an accuracy beyond the limits of these gross appliances; so that it is a truism with a probable error—small, but not infinitely small. The classical laws hold good in the limit when exceedingly large quantum numbers are involved. The system comprising the sun, earth and moon has exceedingly high state-number (p. 198); and the predictability of its configurations is not characteristic of natural phenomena in general but of those involving great numbers of atoms of action—such that we are concerned not with individual but with average behaviour.

Causality applies to the domain of material-substance. It ensures predictability.

Human life is proverbially uncertain; few things are more certain than the solvency of a life-insurance company. The average law is so trustworthy that it may be considered predestined that half the children now born will survive the age of x years. But that does not tell us whether the span of life of young A. McB. is already written in the book of fate, or whether there is still time to alter it by teaching him not to run in front of motorbuses. The eclipse in 1999 is as safe as the balance of a life-insurance company; the next quantum jump of an atom is as uncertain as your life and mine.

Certain patterns may be predicted on the basis of average behavior. Thus we may use statistical methods to predict behavior where large numbers are concerned. Uncertainty lies in singular events at atomic level.

We are thus in a position to answer the main argument for a predetermination of the future, viz. that observation shows the laws of Nature to be of a type which leads to definite predictions of the future, and it is reasonable to expect that any laws which remain undiscovered will conform to the same type. For when we ask what is the characteristic of the phenomena that have been successfully predicted, the answer is that they are effects depending on the average configurations of vast numbers of individual entities. But averages are predictable because they are averages, irrespective of the type of government of the phenomena underlying them.

Averages are predictable because they are averages, irrespective of the type of government of the phenomena underlying them.

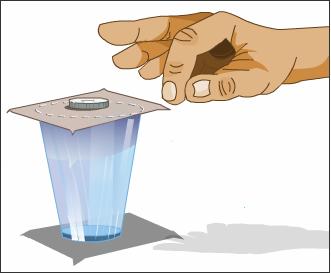

Considering an atom alone in the world in State 3, the classical theory would have asked, and hoped to answer, the question, What will it do next? The quantum theory substitutes the question, Which will it do next? Because it admits only two lower states for the atom to go to. Further, it makes no attempt to find a definite answer, but contents itself with calculating the respective odds on the jumps to State 1 and State 2. The quantum physicist does not fill the atom with gadgets for directing its future behaviour, as the classical physicist would have done; he fills it with gadgets determining the odds on its future behaviour. He studies the art of the bookmaker not of the trainer.

Quantum mechanics deals not with certainties but with probabilities of certain behaviors.

Thus in the structure of the world as formulated in the new quantum theory it is predetermined that of 500 atoms now in State 3, approximately 400 will go on to State 1 and 100 to State 2—in so far as anything subject to chance fluctuations can be said to be predetermined. The odds of 4 to 1 find their appropriate representation in the picture of the atom; that is to say, something symbolic of a 4 : 1 ratio is present in each of the 500 atoms. But there are no marks distinguishing the atoms belonging to the group of 100 from the 400. Probably most physicists would take the view that although the marks are not yet shown in the picture, they are nevertheless present in Nature; they belong to an elaboration of the theory which will come in good time. The marks, of course, need not be in the atom itself; they may be in the environment which will interact with it. For example, we may load dice in such a way that the odds are 4 to 1 on throwing a 6. Both those dice which turn up 6 and those which do not have these odds written in their constitution—by a displaced position of the centre of gravity. The result of a particular throw is not marked in the dice; nevertheless it is strictly causal (apart perhaps from the human element involved in throwing the dice) being determined by the external influences which are concerned. Our own position at this stage is that future developments of physics may reveal such causal marks (either in the atom or in the influences outside it) or it may not. Hitherto whenever we have thought we have detected causal marks in natural phenomena they have always proved spurious, the apparent determinism having come about in another way. Therefore we are inclined to regard favourably the possibility that there may be no causal marks anywhere.

But, it will be said, it is inconceivable that an atom can be so evenly balanced between two alternative courses that nowhere in the world as yet is there any trace of the ultimately deciding factor. This is an appeal to intuition and it may fairly be countered with another appeal to intuition. I have an intuition much more immediate than any relating to the objects of the physical world; this tells me that nowhere in the world as yet is there any trace of a deciding factor as to whether I am going to lift my right hand or my left. It depends on an unfettered act of volition not yet made or foreshadowed.* My intuition is that the future is able to bring forth deciding factors which are not secretly hidden in the past.

* It is fair to assume the trustworthiness of this intuition in answering an argument which appeals to intuition; the assumption would beg the question if we were urging the argument independently.

Looking at the behavior of electrons in a double-slit experiment, we may say that the odds being definite in terms of behavior are determined by the underlying continuum.

The position is that the laws governing the microscopic elements of the physical world—individual atoms, electrons, quanta—do not make definite predictions as to what the individual will do next. I am here speaking of the laws that have been actually discovered and formulated on the old quantum theory and the new. These laws indicate several possibilities in the future and state the odds on each. In general the odds are moderately balanced and are not tempting to an aspiring prophet. But short odds on the behaviour of individuals combine into very long odds on suitably selected statistics of a number of individuals; and the wary prophet can find predictions of this kind on which to stake his credit—without serious risk. All the successful predictions hitherto attributed to causality are traceable to this. It is quite true that the quantum laws for individuals are not incompatible with causality; they merely ignore it. But if we take advantage of this indifference to reintroduce determinism at the basis of world structure it is because our philosophy predisposes us that way, not because we know of any experimental evidence in its favour.

We might for illustration make a comparison with the doctrine of predestination. That theological doctrine, whatever may be said against it, has hitherto seemed to blend harmoniously with the predetermination of the material universe. But if we were to appeal to the new conception of physical law to settle this question by analogy the answer would be :—The individual is not predestined to arrive at either of the two states, which perhaps may here be sufficiently discriminated as State 1 and State 2; the most that can be considered already settled is the respective odds on his reaching these states.

.