Reference: Beginning Physics II

Chapter 6: MAGNETISM-EFFECT OF THE FIELD

.

KEY WORD LIST

Magnetic Force, Magnetic Field, Circular Motion, Mass Spectrometer, Hall Effect, Semiconductor, Velocity Selector, Magnetic Torque, Magnetic Dipole Moment, Motor

.

GLOSSARY

For details on the following concepts, please consult Chapter 6.

MAGNETIC FIELD (B)

The magnetic field is a vector and is the link between the two moving charges that interact with each other. One of the charges is the source of the field, and this field, in turn, has the effect of exerting a force on the second moving charge. For magnetic field, we use the symbol B.

The unit for a magnetic field is a tesla (T) in our system. A more common unit which is widely used in practice is the gauss (G). One gauss equals 10-4 tesla. The strength of the magnetic field near the surface of the earth is approximately one gauss.

MAGNETIC FORCE (F)

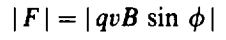

Experimentally we find that, in addition to the electrical force, there is also a force exerted by one moving charge on another moving charge. This force is the magnetic force. The formula for the magnitude of the force is:

Where the charge q is moving with velocity v when the angle between the vectors v and B is φ.

We have used absolute value signs, since the magnitude is always positive. The sign of q does not affect the magnitude of the force. It will, however, affect the direction of the force. Note that the force is zero when the velocity and the magnetic field are along the same line. Also, the largest force occurs when the velocity is perpendicular to the magnetic field.

The magnetic force for a current in the wire is:

The direction of the force is perpendicular to both v and B, and it is therefore necessary to consider the problem in three dimensions. The force points in the direction a right hand screw moves as it rotates from v to B.

CIRCULAR MOTION

A charged particle moving at constant speed at right angles to a magnetic field executes a circular motion in the plane perpendicular to B, because the force is always perpendicular to the direction of the motion. The magnitude of the magnetic force must equal the centripetal force required and we can therefore say that,

This is a formula for the radius of the circle traversed by the particle of mass, m, charge, q, moving with a velocity, v, in a perpendicular magnetic field, B.

SIGN OF THE CHARGE

If one has a charged particle of unknown sign, one can use the circular motion created by a magnetic field to determine the sign of the charge. It may also be used to determine the mass of a charged particle.

MASS SPECTROMETER

A mass spectrometer is an apparatus for separating isotopes, molecules, and molecular fragments according to mass. The sample is vaporized and ionized, and the ions are accelerated in an electric field and deflected by a magnetic field into a curved trajectory that gives a distinctive mass spectrum.

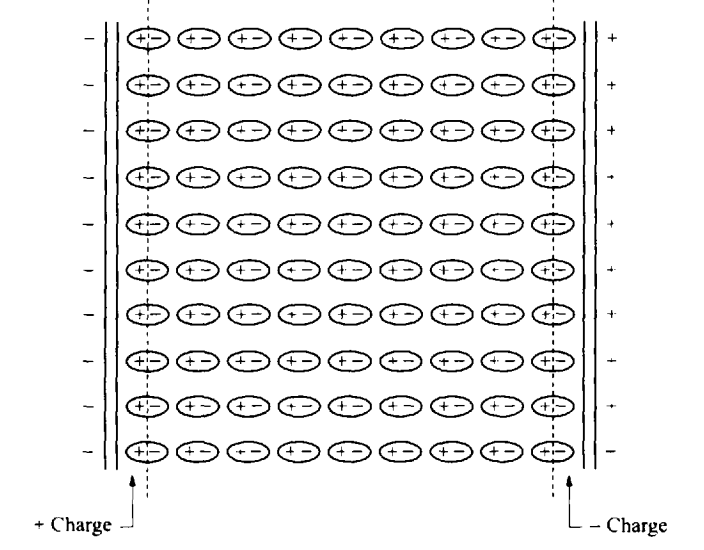

HALL EFFECT

Hall Effect is the production of a potential difference across an electrical conductor when a magnetic field is applied in a direction perpendicular to that of the flow of current.

SEMICONDUCTOR

A semiconductor is a material which has an electrical conductivity value falling between that of a conductor, such as copper, and an insulator, such as glass. A semiconductor’s resistivity falls as its temperature rises, in contrast to normal conductors (i.e. metals) whose resistivity rises with temperature.

VELOCITY SELECTOR

By using a combination of both electric and magnetic fields, we can produce a mechanism to separate out particles of a particular velocity. This is known as a velocity selector.

When the electric force is equal and opposite to the magnetic force, E = vB, or v = E/B. For a velocity of v = E/B there is no force to deflect the particle, and it will travel in a straight line. We can choose the velocity we want by varying E, simply by changing the potential difference across the two plates, which is producing the electric field.

MAGNETIC TORQUE

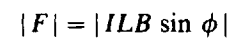

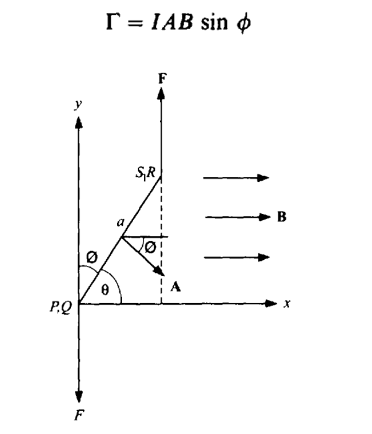

It is useful to define a vector area for the coil, A, whose magnitude is A = ab, and whose direction is perpendicular to the plane of the coil. The ±direction of A is determined by the right-hand rule. Curl the fingers of your right-hand around the coil in the direction of the current. Your thumb then points in the positive A direction. Thus φ is the angle between A (area vector) and B (magnetic field), as can be seen below. We see that in general the torque is given by

where Γ tends to rotate the coil in the same direction as rotating the vector A through φ to B. When A is parallel to B, φ = 0 and the torque is zero.

MAGNETIC DIPOLE MOMENT

We define a new vector, M, the magnetic dipole moment of the coil, whose magnitude is IA and whose direction is the same as A. If the coil consists of several turns, then each turn has a magnetic moment IA, and the entire coil has a magnetic moment NIA, where N is the number of turns in the coil. The torque will turn the coil in the direction of making M point in the direction of B.

Although this result was derived for the special case of a rectangle, the result is valid for any coil shape, with the moment of the coil equaling M = NIA, and the torque on the coil equaling MB sin φ, with the usual counter-clockwise, clockwise conventions.

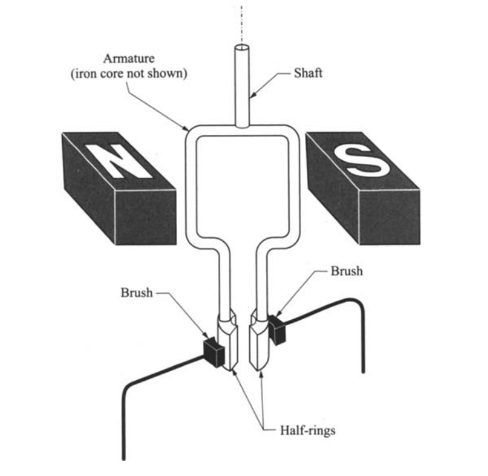

MOTOR

This phenomenon of a torque on a coil can be used to build a motor, which will continuously rotate in the magnetic field. Such motors are built by constructing a coil from many turns (to increase M and thereby, the torque), and suspending the coil on an axis in a constant magnetic field. The direction of the current in the coil is chosen to make the coil rotate in one particular direction, for instance clockwise. When the coil passes the y axis the direction of the torque would normally reverse, making the coil turn counter-clockwise. In order to prevent this from happening, we arrange to have the current direction reverse as the coil passes through the y axis, thus maintaining a clockwise torque. This is accomplished by the split in the rings where the current enters from the source of EMF.

.