Reference: The Book of Physics

Note: The original text is provided below.

Previous / Next

Summary

A preferred frame of space would be one corresponding to an observer absolutely at rest. It was assumed not to exist. [NOTE: A black hole with infinite inertia at the center of the galaxy may provide such a frame, but this was neither known to Newton nor to Einstein.]

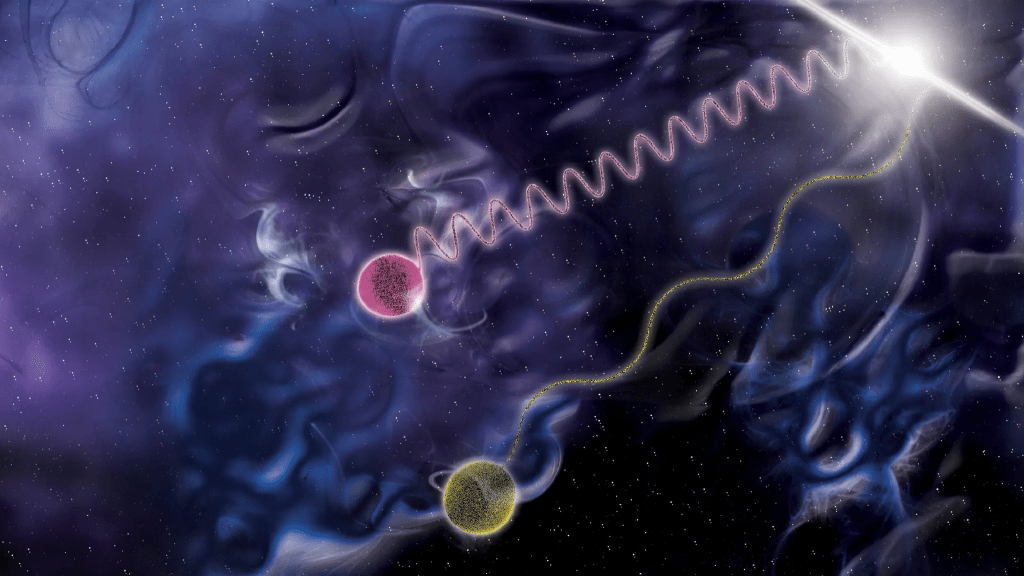

The wave theory assumes light to be a disturbance in an ethereal medium. Einstein denied the existence of aether in the sense that light did not need a medium to propagate through as it was not a disturbance. Later Einstein reinstated aether as a substance that filled the space along with the electromagnetic energy and matter. It had its own characteristics that were yet to be determined.

Einstein established equivalence between energy and matter, thus identifying both as substances. Today this ethereal medium is described through a complexity of mathematical symbols and equations that have been interpreted in different ways. But, in reality, it is a substance much like energy and matter. This is consistent with what Faraday had postulated. (See Faraday 1846: Thoughts on Ray Vibrations)

.

Comments

The Theory of Substance states that substance is anything that is substantial enough to be sensed. We can sense matter, energy and thought. The postulated aether may be thought, but that is yet to be established. The invariant property of substance is “consistency” which is called mass/inertia for matter. It is defined by frequency for energy; and it is relatively zero for aether.

We may say that aether, energy and matter provide a spectrum of substance of increasing inertia (consistency). The higher is the inertia, the lesser is the velocity. A body of infinite inertia, such as, a black hole at the center of the galaxy, shall be very close to having the state of rest. By relating inertia to velocity we can separate science fiction from science. For example, we cannot ever have matter traveling at the speed of light.

The inverse relationship between velocity and consistency provides us with a scale of absolute motion as well as absolute inertia for matter, energy and aether. Every material body may be plotted somewhere on this scale. This scale extends to atomic realm and beyond. The postulated aether at the other end of the scale shall have zero consistency and infinite velocity.

The space between atoms, which is filled by electromagnetic energy coincides with the space through which the whole material body is moving. In short, the space is filled by aether, energy or matter. There is no empty space.

.

Original Text

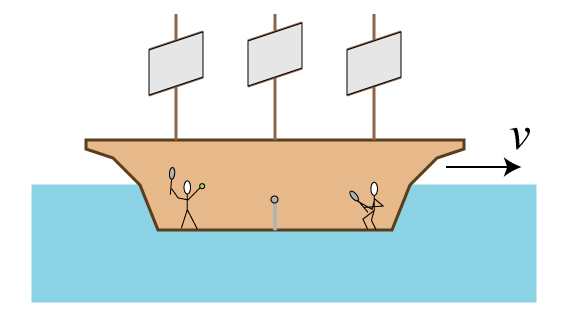

The theory of relativity is evidently bound up with the impossibility of detecting absolute velocity; if in our quarrel with the nebular physicists one of us had been able to claim to be absolutely at rest, that would be sufficient reason for preferring the corresponding frame. This has something in common with the well-known philosophic belief that motion must necessarily be relative. Motion is change of position relative to something-, if we try to think of change of position relative to nothing the whole conception fades away. But this does not completely settle the physical problem. In physics we should not be quite so scrupulous as to the use of the word absolute. Motion with respect to aether or to any universally significant frame would be called absolute.

No aethereal frame has been found. We can only discover motion relative to the material landmarks scattered casually about the world; motion with respect to the universal ocean of aether eludes us. We say, “Let V be the velocity of a body through the aether”, and form the various electromagnetic equations in which V is scattered liberally. Then we insert the observed values, and try to eliminate everything that is unknown except V. The solution goes on famously; but just as we have got rid of the other unknowns, behold! V disappears as well, and we are left with the indisputable but irritating conclusion: 0 = 0.

This is a favourite device that mathematical equations resort to, when we propound stupid questions. If we tried to find the latitude and longitude of a point north-east from the north pole we should probably receive the same mathematical answer. “Velocity through aether” is as meaningless as “north-east from the north pole”.

This does not mean that the aether is abolished. We need an aether. The physical world is not to be analyzed into isolated particles of matter or electricity with featureless interspace. We have to attribute as much character to the interspace as to the particles, and in present-day physics quite an army of symbols is required to describe what is going on in the interspace. We postulate aether to bear the characters of the interspace as we postulate matter or electricity to bear the characters of the particles. Perhaps a philosopher might question whether it is not possible to admit the characters alone without picturing anything to support them—thus doing away with aether and matter at one stroke. But that is rather beside the point.

In the last century it was widely believed that aether was a kind of matter, having properties such as mass, rigidity, motion, like ordinary matter. It would be difficult to say when this view died out. It probably lingered longer in England than on the continent, but I think that even here it had ceased to be the orthodox view some years before the advent of the relativity theory. Logically it was abandoned by the numerous nineteenth-century investigators who regarded matter as vortices, knots, squirts, etc., in the aether; for clearly they could not have supposed that aether consisted of vortices in the aether. But it may not be safe to assume that the authorities in question were logical.

Nowadays it is agreed that aether is not a kind of matter. Being non-material, its properties are sui generis. We must determine them by experiment; and since we have no ground for any preconception, the experimental conclusions can be accepted without surprise or misgiving. Characters such as mass and rigidity which we meet with in matter will naturally be absent in aether; but the aether will have new and definite characters of its own. In a material ocean we can say that a particular particle of water which was here a few moments ago is now over there; there is no corresponding assertion that can be made about the aether. If you have been thinking of the aether in a way which takes for granted this property of permanent identification of its particles, you must revise your conception in accordance with the modern evidence. We cannot find our velocity through the aether; we cannot say whether the aether now in this room is flowing out through the north wall or the south wall. The question would have a meaning for a material ocean, but there is no reason to expect it to have a meaning for the non-material ocean of aether.

The aether itself is as much to the fore as ever it was, in our present scheme of the world. But velocity through aether has been found to resemble that elusive lady Mrs. Harris; and Einstein has inspired us with the daring skepticism—”I don’t believe there’s no sich a person”.

.