Reference: SC: Psychology

NOTE: Text in color contains Vinaire’s comments.

The Birth of Psychiatric Medicine (9th-11th Centuries CE)

.

The Founding of Psychiatric Institutions

The Islamic Golden Age (roughly 8th-13th centuries CE) witnessed the most revolutionary advances in the treatment of mental illness during the first millennium. Islamic physicians synthesized Greek, Persian, and Indian medical knowledge while making groundbreaking innovations that would not be matched in the West until the modern era.

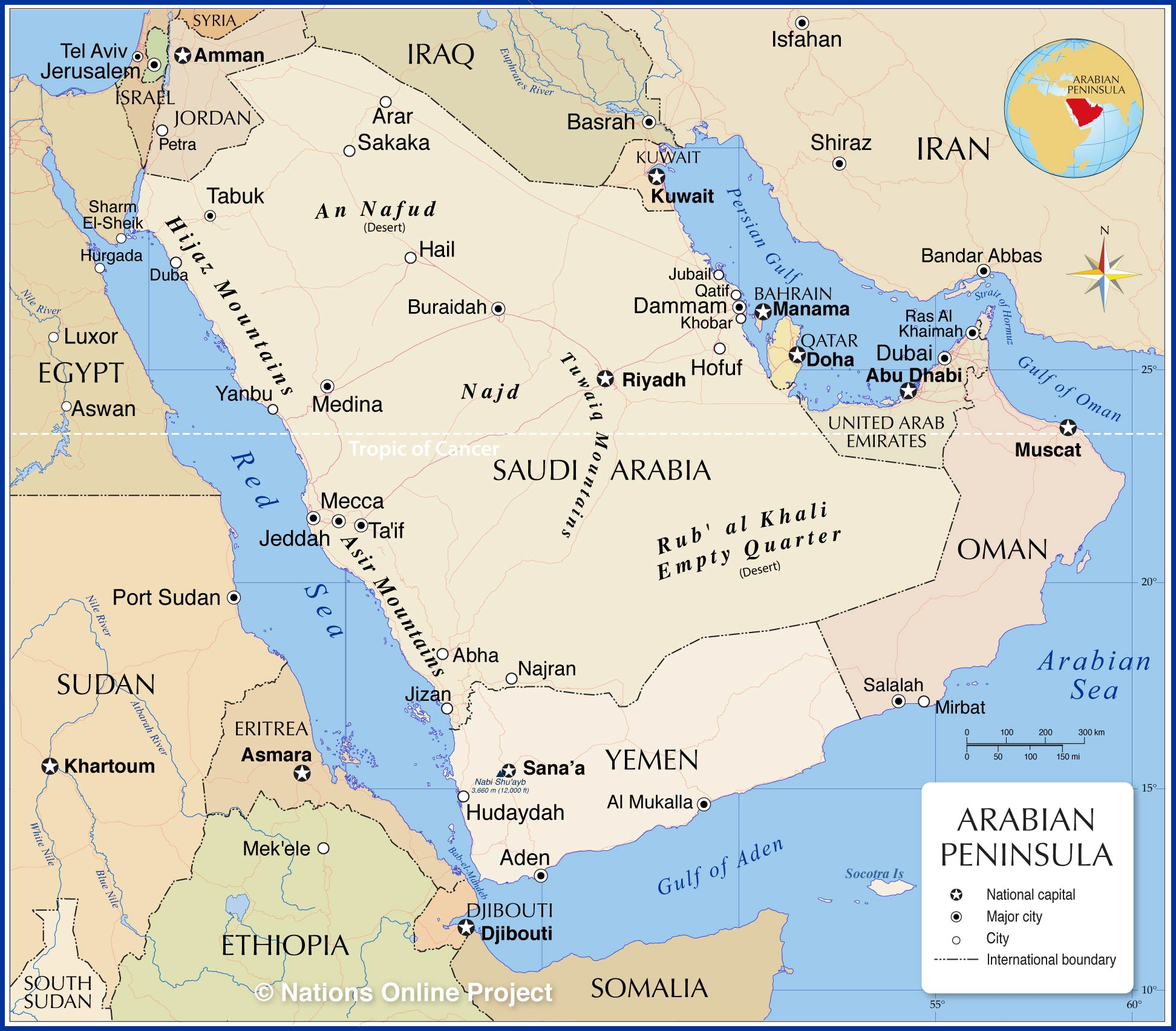

Abu Bakr Muhammad Ibn Zakariya Al-Razi (Rhazes, 865-925 CE) achieved a milestone in psychiatric history by establishing the first dedicated psychiatric ward in Baghdad. This represented a paradigmatic shift in how mental illness was conceptualized and treated. Al-Razi “viewed mental illnesses as conditions that required medical intervention, challenging the prevalent notions that attributed such ailments to supernatural causes or moral failings”. His approach was “revolutionary for his time”—he insisted that “mental disorders should be recognized and treated as medical conditions”.

In these psychiatric wards, Al-Razi “conducted thorough clinical observations of patients with psychiatric conditions and implemented treatment strategies involving diet, medication, occupational therapy, aromatherapy, baths, and music therapy”. The comprehensiveness of treatment reflected a holistic understanding that mental illness affected the whole person. Al-Razi “gave priority to the doctor-patient relationship” and “advised physicians on how to keep the respect and confidence of their patients”, recognizing that the therapeutic relationship itself was curative.

Al-Razi developed innovative psychotherapeutic approaches that anticipated modern psychotherapy by a millennium. He “advocated for psychotherapy,” emphasizing that “positive remarks from doctors could uplift patients, enhance their well-being, and facilitate a faster recovery”. He believed that “a sudden, intense emotional reaction could rapidly improve psychological, psychosomatic, and organic disorders”, employing what he called “a simple but dynamic approach” to psychotherapy. In one famous case, Al-Razi treated Prince Mansur of Ray for severe joint pain through an elaborate psychological intervention—staging an emotionally shocking confrontation in a bathhouse that successfully mobilized the prince to move when conventional treatments had failed.

Al-Razi made crucial diagnostic distinctions. He clarified that “a Majnun (insane) is not epileptic, as an epileptic person is otherwise healthy except during seizures”. He distinguished different types of melancholia, noting that “the reason is merely misdirected” rather than destroyed. Remarkably, he “asserted that religious compulsions could be overcome by reason to achieve better mental health,” accomplishing “a primary form of cognitive therapy for obsessive behavior”. He also advocated that “mental health and self-esteem are crucial factors influencing a person’s overall health”, anticipating modern biopsychosocial models.

The Islamic revolution was the insistence that mental disorders should be recognized and treated as medical conditions. The establishment of the first dedicated psychiatric ward in Baghdad represented a paradigmatic shift in how mental illness was conceptualized and treated. The therapeutic relationship was an important part of the treatment.

.

Comprehensive Biopsychosocial Systems

Abu Zayd al-Balkhi (9th century CE) was “the first to discuss the interconnectivity between physical and mental well-being by linking illness with the nafs (self/soul) to the development of physical ailments”. In his treatise Masalih al-Abdan wa al-Anfus (“Sustenance of the Body and Soul”), he “developed approaches that we would now view as cognitive and talking therapy”. Al-Balkhi’s interventions included instructing individuals “to keep helpful cognitions at hand during times of distress,” employing “persuasive talking, preaching, and advising,” differentiating “between normal and extreme emotional responses to situations,” and studying “the development of coping mechanisms for anger, fear, sadness, and obsessions”. This framework, connecting cognitions and pathological behaviors, bears striking resemblance to modern cognitive behavioral therapy.

Al-Balkhi was also notable for “distinguishing between neuroses and psychosis, classifying neuroses into four categories: fear and anxiety (al-khawf wa al-faza’), anger and aggression (al-ghadab wa al-haraq), sadness and depression (al-huzn wa al-inhizam), and obsessions (al-waswas)”. This categorical system demonstrated sophisticated clinical observation and represented an early psychiatric nosology.

Al-Akhawayni Bukhari (?-983 CE) gained such renown for his treatment of mentally ill patients that he became known as “Bejeshk-e Divanehgan” (The Doctor of the Insane). His work Hidayat contained detailed chapters on various mental conditions: “Mania,” “Malikhulia” (Melancholia), “Kabus” (Nightmare), “Ghotrab” (Dementia), and “Khonagh-o-Rahem” (Conversion Disorder). Al-Akhawayni made the crucial observation that melancholia “results from the impact of black bile on the brain”, explicitly localizing mental illness in neurological substrates.

He classified patients with melancholia into distinct subtypes based on clinical presentation. The first group exhibited “fear with no definite etiology, self-laughing, self-crying, and speaking meaninglessly”—symptoms we would now associate with major depressive disorder with psychotic features. A second group claimed to possess stunning abilities, “introduced themselves as a prophet or king,” or believed they had “turned into other beings, like hens and roosters, and mimicked their behaviors”—presentations consistent with grandiose delusions seen in bipolar disorder with psychotic features or schizophrenia. Al-Akhawayni emphasized nutritional interventions, believing that “some foods, such as wholemeal bread, beef, and salted fish, can be beneficial to the melancholics’ condition”.

The interconnectivity between physical and mental well-being was emphasized by linking illness with the inner self, that has desires, emotions, and free will, to the development of physical ailments. Clear distinction was made between neuroses and psychosis.

.

The Synthesis of Avicenna

Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 980-1037 CE) produced The Canon of Medicine, which “was the basis for studying medicine in the East and the West for multiple centuries”. The Canon “discusses, among other things, the structure of psychological apparatus of human being and the connection of psychological functions with the brain as well as the role of psyche in etiology of somatic diseases”. Avicenna’s work represented the pinnacle of medieval understanding of mental illness, integrating philosophical psychology with clinical observation.

Avicenna provided detailed phenomenological descriptions of mental disorders. He distinguished between early and chronic phases of melancholia: the early phase involved “suspicions of evil, fear without cause, quick anger, involuntary muscle movements, dizziness, and tinnitus,” while the chronic phase showed “moaning, deep suspicion, profound sadness, restlessness, and delusions” including fears “that the sky may fall on one’s head” or of “being swallowed by the earth”. Avicenna was “among the first physicians to document that anger often serves as a transitional state between melancholic depression and mania—what psychiatry now calls the ‘switch’ phenomenon”.

Remarkably, Avicenna recognized what “wouldn’t be formally recognized by modern psychiatry for nearly a millennium: what we now call ‘mixed states,’ where features of depression and mania occur together”. He noted that some melancholic patients would show “increased libido, involuntary laughter, and even grandiose thoughts like imagining ‘that one is king’”.

Avicenna explored the psychology of death anxiety, identifying it as “a universal fear” with three cognitive causes: “(a) ignorance as to what death is, (b) uncertainty of what is to follow after death and (c) supposing that after death, the soul may cease to exist”. This analysis demonstrated sophisticated understanding of how cognitive interpretations generate emotional states.

Avicenna’s understanding of psychosomatic medicine was centuries ahead of his time. “He recognized the influence of emotional and mental states on physical health, suggesting that pain perception could be shaped by factors such as stress, anxiety, and sadness,” while “positive emotions and mental tranquility could reduce it”. This dual focus on psychological and physical conditions made it “critical for physicians to address both” aspects of patient care.

There was better understanding of the structure of psychological apparatus of human being, the connection of psychological functions with the brain, the role of psyche in the causation of somatic diseases, and of psychosomatic medicine.

.

Institutional Care and Cultural Context

The Islamic world developed sophisticated institutional care for mental illness through bimaristans (hospitals). These institutions had “separate wards for different illnesses, patients suffering from anxiety or showing signs of psychological distress were treated” with comprehensive modalities. The Mansuri Hospital in Cairo provided “medical treatment for Muslim patients, male and female, rich and poor, from Cairo and the countryside”, emphasizing accessibility regardless of social status. These hospitals included “lecture rooms, a library, as well as a chapel and a mosque”, integrating medical education with treatment.

The cultural context was crucial: “During the Islamic Golden Age, mental disorders were seen as phenomena that existed, requiring clinical assessment and treatment, and categorized and assessed systematically by employing rational judgements and observation rather than cultural beliefs based on supernatural causes”. While “the use of religious and medical forms of healing co-occurred—for instance, the use of prayer and ritual healing in addition to using treatments according to the medical model of the time”—the medical framework remained primary. This stood in stark contrast to medieval Christian Europe, where “discourse of mental illness as result of demons, spirits, spiritual distress, and sin dominated”.

The Islamic world developed sophisticated institutional care for mental illness through hospitals. These hospitals included lecture rooms, a library, as well as a chapel and a mosque, integrating medical education with treatment.

.

Notes:

- Nafs (نَفْس) is an Arabic word meaning the self, soul, psyche, or ego, central to Islamic thought, representing the inner self with desires, emotions, and free will, having both negative (commanding evil) and positive (tranquil) states, requiring spiritual struggle to tame its lower instincts (like lust, anger) towards a higher, peaceful state, often described in stages (like the commanding self, reproaching self, tranquil self). It’s the aspect of the spirit interacting with the physical body, driving actions and choices, distinct from the pure spirit (ruh) but linked to it.

.