Reference: Hinduism

Note: The original Text is provided below.

Previous / Next

This is a world in which good and evil, pleasure and pain, knowledge and ignorance, interweave in about equal proportions. And this is the way things will remain. The purpose of this world is to provide a training ground for the human spirit.

.

Summary

Hinduism believes that the universe extends out from the imperishable and then withdraws periodically. The imperishable is a state of pure potentiality. This oscillation is built into the scheme of things; the universe had no beginning and will have no end. Within the universe there are endless cycles within cycles.

It is a just world in which everyone gets what is deserved and creates his or her own future. It is a world in which good and evil, pleasure and pain, knowledge and ignorance, interweave in about equal proportions. And this is the way things will remain. All dreams of utopia are not just doomed to disappointment because this world cannot be perfected. The purpose of this world is not to rival paradise but to provide a training ground for the human spirit. It is admirably suited to develop character and prepare people to look beyond it.

Hinduism looks at both sides of every major metaphysical issue: the dual and non-dual points of view, both jnana yoga and bhakti yoga, both personal and transpersonal view of God, both merging with God and aspiring to God’s company, and both reality and unreality of the world.

Hinduism believes that God, individual souls and nature have the same divine basis. There are three modes of consciousness under which the world appears: (1) Hallucinations that can be corrected with further perception, (2) the world as it normally appears to the human senses, (3) and a state of superconsciousness in which all reality appears to be one.

From the perspective of the third mode of consciousness, the other two modes appear as dream-like psychological constructs called “Maya.” Maya is tricky in the sense that the world’s materiality and multiplicity pass themselves off as being independently real. But they are real only according to stance from which we see them. Maya is also seductive in the attractiveness in which it presents the world, trapping us within it and leaving us with no desire to journey on.

Hinduism visualizes an ideal society to be one where everyone performs their duties efficiently but dispassionately, “like an actor on the stage.” Thus, people are no longer motivated by their passions, though they still possess them. Worldly affairs continue, but the citizens are relieved of old resentments and are less buffeted by fears and desires.

The world is lila, God’s play. The play is its own point and reward. It is fun in itself, a spontaneous overflow of creative, imaginative energy. From the tireless stream of God’s energy the cosmos flows in endless, graceful reenactment. Seen in perspective, the world is ultimately benign. It has no permanent hell and threatens no eternal damnation. Beyond this world lies the boundless good, which all will achieve in the end.

.

Comments

This world is just fine as it is. It serves its purpose well as a training ground for the human spirit.

.

Original Text

A ground plan of the world as conceived by Hinduism would look something like this: There would be innumerable galaxies comparable to our own, each centering in an earth from which people wend their ways to God. Ringing each earth would be a number of finer worlds above and coarser ones below, to which souls repair between incarnations according to their just desserts.

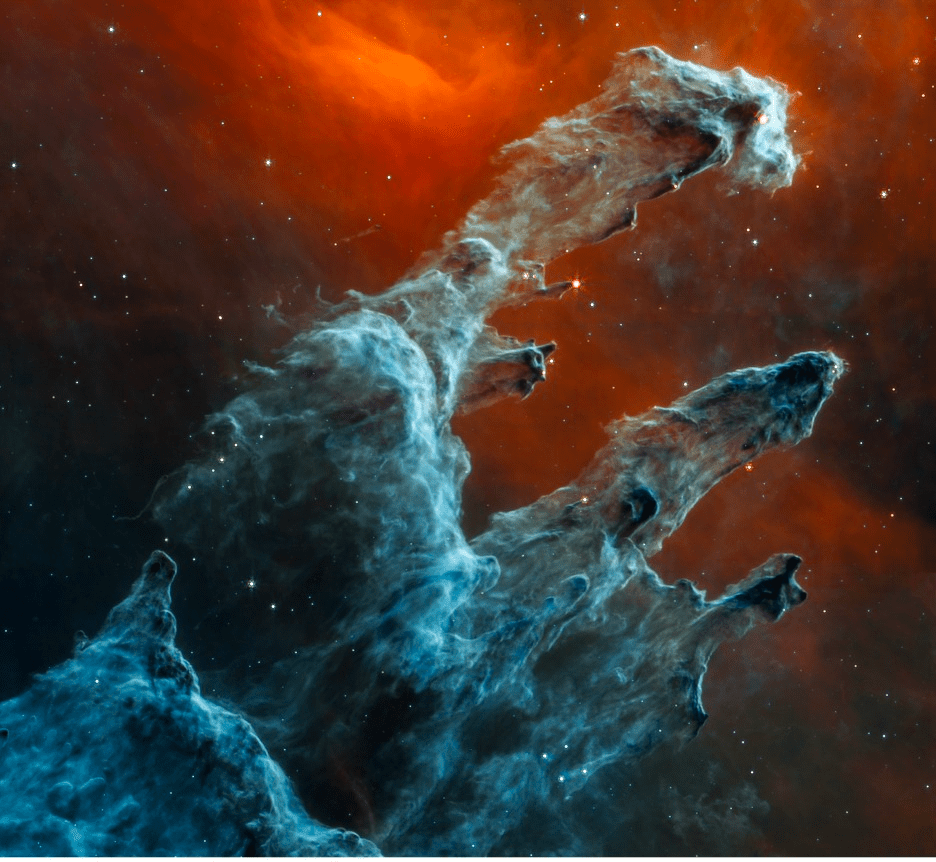

“Just as the spider pours forth its thread from itself and takes it back again, even so the universe grows from the Imperishable.” Periodically the thread is withdrawn; the cosmos collapses into a Night of Brahma, and all phenomenal being is returned to a state of pure potentiality. Thus, like a gigantic accordion, the world swells out and is drawn back in. This oscillation is built into the scheme of things; the universe had no beginning and will have no end. The time frame of Indian cosmology boggles the imagination and may have something to do with the proverbial oriental indifference to haste. The Himalayas, it is said, are made of solid granite. Once every thousand years a bird flies over them with a silk scarf in its beak, brushing their peaks with its scarf. When by this process the Himalayas have been worn away, one day of a cosmic cycle will have elapsed.

When we turn from our world’s position in space and time to its moral character, the first point has already been established in the preceding section. It is a just world in which everyone gets what is deserved and creates his or her own future.

The second thing to be said is that it is a middle world. This is so, not only in the sense that it hangs midway between heavens above and hells below. It is also middle in the sense of being middling, a world in which good and evil, pleasure and pain, knowledge and ignorance, interweave in about equal proportions. And this is the way things will remain. All talk of social progress, of cleaning up the world, of creating the kingdom of heaven on earth—in short, all dreams of utopia—are not just doomed to disappointment; they misjudge the world’s purpose, which is not to rival paradise but to provide a training ground for the human spirit. The world is the soul’s gymnasium, its school and training field. What we do is important; but ultimately, it is important for the discipline it offers our individual character. We delude ourselves if we expect it to change the world fundamentally. Our work in the world is like bowling in an uphill alley; it can build muscles, but we should not think that our rolls will permanently deposit the balls at the alley’s other end. They all roll back eventually, to confront our children if we ourselves have passed on. The world can develop character and prepare people to look beyond it—for these it is admirably suited. But it cannot be perfected. “Said Jesus, blessed be his name, this world is a bridge: pass over, but build no house upon it.” It is true to Indian thought that this apocryphal saying, attributed to the poet Kabir, should have originated on her soil.

If we ask about the world’s metaphysical status, we shall have to continue the distinction we have watched divide Hinduism on every major issue thus far; namely, the one between the dual and the non-dual points of view. On the conduct of life this distinction divides jnana yoga from bhakti yoga; on the doctrine of God it divides the personal from the transpersonal view; on the issue of salvation it divides those who anticipate merging with God from those who aspire to God’s company in the beatific vision. In cosmology an extension of the same line divides those who regard the world as being from the highest perspective unreal from those who believe it to be real in every sense.

All Hindu religious thought denies that the world of nature is self-existent. It is grounded in God, and if this divine base were removed it would instantly collapse into nothingness. For the dualist the natural world is as real as God is, while of course being infinitely less exalted. God, individual souls, and nature are distinct kinds of beings, none of which can be reduced to the others. Non-dualists, on the other hand, distinguish three modes of consciousness under which the world can appear. The first is hallucination, as when we see pink elephants, or when a straight stick appears bent under water. Such appearances are corrected by further perceptions, including those of other people. Second, there is the world as it normally appears to the human senses. Finally, there is the world as it appears to yogis who have risen to a state of superconsciousness. Strictly speaking, this is no world at all, for here every trait that characterizes the world as normally perceived—its multiplicity and materiality—vanishes. There is but one reality, like a brimming ocean, boundless as the sky, indivisible, absolute. It is like a vast sheet of water, shoreless and calm.

The non-dualist claims that this third perspective is the most accurate of the three. By comparison, the world that normally appears to us is maya. The word is often translated “illusion,” but this is misleading. For one thing it suggests that the world need not be taken seriously. This the Hindus deny, pointing out that as long as it appears real and demanding to us we must accept it as such. Moreover, maya does have a qualified, provisional reality.

Were we asked if dreams are real, our answer would have to be qualified. They are real in the sense that we have them, but they are not real inasmuch as what they depict need not exist objectively. Strictly speaking, a dream is a psychological construct, a mental fabrication. The Hindus have something like this in mind when they speak of maya. The world appears as the mind in its normal condition perceives it; but we are not justified in thinking that reality as it is in itself is as it is thus seen. A young child seeing its first movie will mistake the moving pictures for actual objects, unaware that the lion growling from the screen is projected from a booth at the rear of the theater. It is the same with us; the world we see is conditioned, and in that sense projected, by our perceptual mechanisms. To change the metaphor, our sense receptors register only a narrow band of electromagnetic frequencies. With the help of microscopes and other amplifiers, we can detect some additional wavelengths, but superconsciousness must be cultivated to know reality itself. In that state our receptors would cease to refract, like a prism, the pure light of being into a spectrum of multiplicity. Reality would be known as it actually is: one, infinite, unalloyed.

Maya comes from the same root as magic. In saying the world is maya, non-dual Hinduism is saying that there is something tricky about it. The trick lies in the way the world’s materiality and multiplicity pass themselves off as being independently real—real apart from the stance from which we see them—whereas in fact reality is undifferentiated Brahman throughout, even as a rope lying in the dust remains a rope while being mistaken for a snake. Maya is also seductive in the attractiveness in which it presents the world, trapping us within it and leaving us with no desire to journey on.

But again we must ask, if the world is only provisionally real, will it be taken seriously? Will not responsibility flag? Hinduism thinks not. In a sketch of the ideal society comparable to Plato’s Republic, the Tripura Rahasya portrays a prince who achieves this outlook on the world and is freed thereby from “the knots of the heart” and “the identification of the flesh with the Self.” The consequences depicted are far from asocial. Thus liberated, the prince performs his royal duties efficiently but dispassionately, “like an actor on the stage.” Following his teachings and example, his subjects attain a comparable freedom and are no longer motivated by their passions, though they still possess them. Worldly affairs continue, but the citizens are relieved of old resentments and are less buffeted by fears and desires. “In their everyday life, laughing, rejoicing, wearied or angered, they behaved like men intoxicated and indifferent to their own affairs.” Wherefore the sages that visited there called it “the City of Resplendent Wisdom.”

If we ask why Reality, which is in fact one and perfect, is seen by us as many and marred; why the soul, which is really united with God throughout, sees itself for a while as sundered; why the rope appears to be a snake—if we ask these questions we are up against the question that has no answer, any more than the comparable Christian question of why God created the world has an answer. The best we can say is that the world is lila, God’s play. Children playing hide and seek assume various roles that have no validity outside the game. They place themselves in jeopardy and in conditions from which they must escape. Why do they do so when in a twinkling they could free themselves by simply stepping out of the game? The only answer is that the game is its own point and reward. It is fun in itself, a spontaneous overflow of creative, imaginative energy. So too in some mysterious way must it be with the world. Like a child playing alone, God is the Cosmic Dancer, whose routine is all creatures and all worlds. From the tireless stream of God’s energy the cosmos flows in endless, graceful reenactment.

Those who have seen images of the goddess Kali dancing on a prostrate body while holding in her hands a sword and a severed head; those who have heard that there are more Hindu temples dedicated to Shiva (whose haunt is the crematorium and is God in his aspect of destroyer) than there are temples to God in the form of creator and preserver combined—those who know these things will not jump quickly to the conclusion that the Hindu worldview is gentle. What they overlook is that what Kali and Shiva destroy is the finite in order to make way for the infinite.

Because Thou lovest the Burning-ground,

I have made a Burning-ground of my heart—

That Thou, Dark One, hunter of the Burning-ground,

Mayest dance Thy eternal dance. (Bengali hymn)

Seen in perspective, the world is ultimately benign. It has no permanent hell and threatens no eternal damnation. It may be loved without fear; its winds, its ever-changing skies, its plains and woodlands, even the poisonous splendor of the lascivious orchid—all may be loved provided that they are not dallied over indefinitely. For all is maya, lila, the spell-binding dance of the cosmic magician, beyond which lies the boundless good, which all will achieve in the end. It is no accident that the only art form India failed to produce was tragedy.

In sum: To the question, “What kind of world do we have?” Hinduism answers:

- A multiple world that includes innumerable galaxies horizontally, innumerable tiers vertically, and innumerable cycles temporally.

- A moral world in which the law of karma is never suspended.

- A middling world that will never replace paradise as the spirit’s destination.

- A world that is maya, deceptively tricky in passing off its multiplicity, materiality, and dualities as ultimate when they are actually provisional.

- A training ground on which people can develop their highest capacities.

- A world that is lila, the play of the Divine in its Cosmic Dance—untiring, unending, resistless, yet ultimately beneficent, with a grace born of infinite vitality.

.