Reference: The Story of Philosophy

This paper presents Chapter VIII Section 4 from the book THE STORY OF PHILOSOPHY by WILL DURANT. The contents are from the 1933 reprint of this book by TIME INCORPORATED by arrangement with Simon and Schuster, Inc.

The paragraphs of the original material (in black) are accompanied by brief comments (in color) based on the present understanding.

.

IV. Biology: The Evolution of Life

The second and third volumes of the Synthetic Philosophy appeared in 1872 under the title of Principles of Biology. They revealed the natural limitations of a philosopher invading a specialist’s field; but they atoned for errors of detail by illuminating generalizations that gave a new unity and intelligibility to vast areas of biological fact.

Spencer provided illuminating generalizations to vast areas of biological fact.

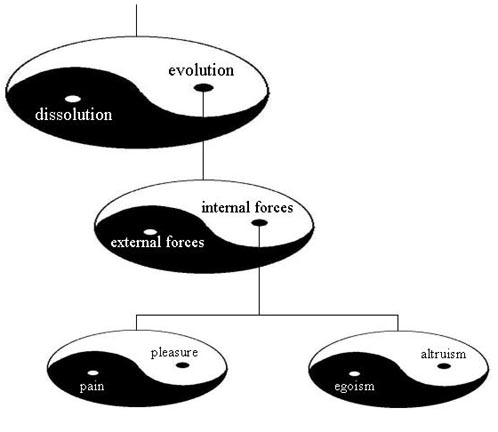

Spencer begins with a famous definition: “Life is the continuous adjustment of internal relations to external relations.” The completeness of life depends on the completeness of this correspondence; and life is perfect when the correspondence is perfect. The correspondence is not a merely passive adaptation; what distinguishes life is the adjustment of internal relations in anticipation of a change in external relations, as when an animal crouches to avoid a blow, or a man makes a fire to warm his food. The defect of the definition lies not merely in its tendency to neglect the remolding activity of the organism upon the environment, but in its failure to explain what is that subtle power whereby an organism is enabled to make these prophetic adjustments that characterize vitality. In a chapter added to later editions, Spencer was forced to discuss “The Dynamic Element in Life,” and to admit that his definition had not really revealed the nature of life. “We are obliged to confess that Life in its essence cannot be conceived in physico-chemical terms.” He did not realize how damaging such an admission was to the unity and completeness of his system.

Spencer begins with a famous definition: “Life is the continuous adjustment of internal relations to external relations.” But his definition had not really revealed the nature of life.

As Spencer sees in the life of the individual an adjustment of internal to external relations, so he sees in the life of the species a remarkable adjustment of reproductive fertility to the conditions of its habitat. Reproduction arises originally as a re-adaptation of the nutritive surface to the nourished mass; the growth of an amoeba, for example, involves an increase of mass much more rapid than the increase in the surface through which the mass must get its nourishment, Division, budding, spore-formation, and sexual reproduction have this in common, that the ratio of mass to surface is reduced, and the nutritive balance is restored. Hence the growth of the individual organism beyond a certain point is dangerous; and normally growth gives way, after a time, to reproduction.

Spencer sees in the life of the species a remarkable adjustment of reproductive fertility to the conditions of its habitat. The ratio of mass to surface is prone to adjustment to establish the nutritive balance.

On the average, growth varies inversely with the rate of energy-expenditure; and the rate of reproduction varies inversely with the degree of growth. “It is well known to breeders that if a filly is allowed to bear a foal, she is thereby prevented from reaching her proper size. … As a converse fact, castrated animals, as capons and notably cats, often become larger than their unmutilated associates.” The rate of reproduction tends to fall as the development and capability of the individual progress. “When, from lowness of organization, the ability to contend with external dangers is small, there must be great fertility to compensate for the consequent mortality; otherwise the race must die out. When, on the contrary, high endowments give much capacity for self-preservation, a correspondingly low degree of fertility is requisite,” lest the rate of multiplication should outrun the supply of food. In general, then, there is an opposition of individuation and genesis, or individual development and fertility. The rule holds for groups and species more regularly than for individuals: the more highly developed the species or the group, the lower will its birth-rate be. But it holds for individuals too, on the average. For example, intellectual development seems hostile to fertility. “Where exceptional fertility exists, there is sluggishness of mind, and where there has been, during education, excessive expenditure in mental action, there frequently follows a complete or partial infertility. Hence the particular kind of further evolution which Man is hereafter to undergo is one which, more than any other, may be expected to cause a decline in his power of reproduction.” Philosophers are notorious for shirking parentage. In woman, on the other hand, the arrival of motherhood normally brings a diminution of intellectual activity; and perhaps her shorter adolescence is due to her earlier sacrifice to reproduction.

The more highly developed the species or the group, the lower will its birth-rate be. On the average, the rate of reproduction varies inversely with the degree of growth.

Despite this approximate adaptation of birth-rate to the needs of group survival, the adaptation is never complete, and Malthus was right in his general principle that population tends to outrun the means of subsistence. “From the beginning this pressure of population has been the proximate cause of progress. It produced the original diffusion of the race. It compelled men to abandon predatory habits and take to agriculture. It led to the clearing of the earth’s surface. It forced men into the social state, … and developed the social sentiments. It has stimulated to progressive improvements in production, and to increased skill and intelligence.” It is the chief cause of that struggle for existence through which the fittest are enabled to survive, and through which the level of the race is raised.

Malthus was also right in his general principle that population tends to outrun the means of subsistence. It is the chief cause of that struggle for existence through which the fittest are enabled to survive, and through which the level of the race is raised.

Whether the arrival of the fittest is due chiefly to spontaneous favorable variations, or to the partial inheritance of characters or capacities repeatedly acquired by successive generations, is a question on which Spencer took no dogmatic stand; he accepted Darwin’s theory gladly, but felt that there were facts which it could not explain, and which compelled a modified acceptance of Lamarckian views. He defended Lamarck with fine vigor in his controversy with Weismann, and pointed out certain defects in the Darwinian theory. In those days Spencer stood almost alone on the side of Lamarck; it is of some interest to note that today the neo-Lamarckians include descendants of Darwin, while the greatest contemporary English biologist gives it as the view of present-day students of genetics that Darwin’s particular theory (not, of course the general theory) of evolution must be abandoned.

Spencer accepted Darwin’s theory gladly, but felt that there were facts which it could not explain, and which compelled a modified acceptance of Lamarckian views.

.