Reference: Hinduism

Note: The original Text is provided below.

Previous / Next

To the bhakta, for whom feelings are more real than thoughts, God appears different.

.

Summary

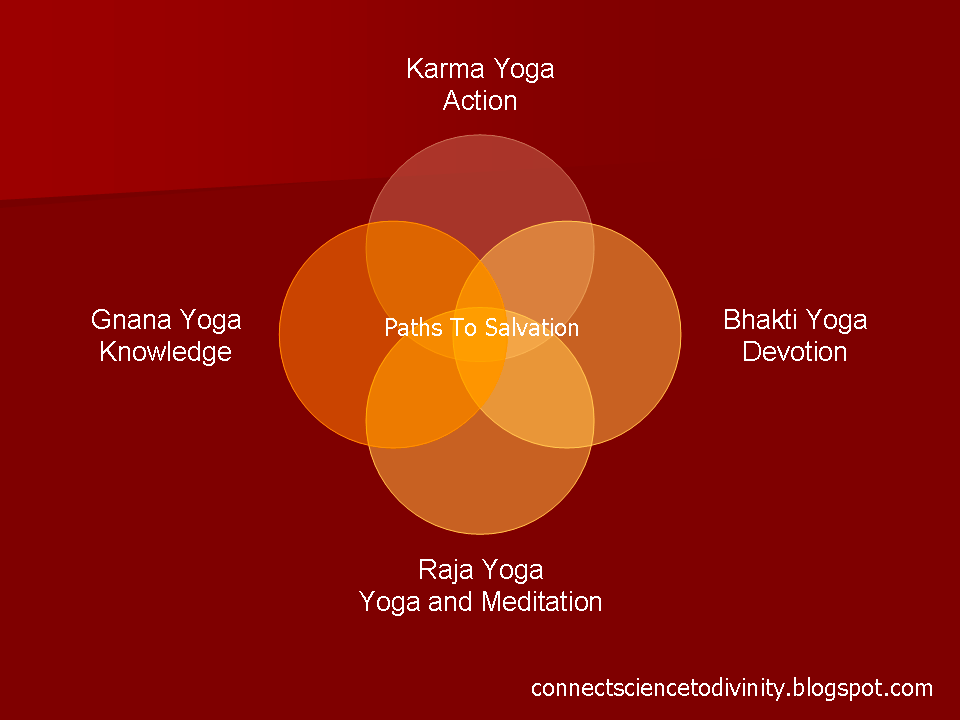

Most people find the yoga of knowledge (jnana yoga) to be difficult. By and large, life is powered less by reason than by emotion; and of the many emotions that crowd the human heart, the strongest is love. Therefore, to most people, the yoga of love (bhakti yoga) comes more naturally.

The aim of bhakti yoga is to direct toward God the love that lies at the base of every heart. The minds of the bhakta move constantly toward that which they love—the qualities, which they associate with God. It is transferring one’s natural attachments towards things to an attachment to God. In jnana yoga the guiding image is of an infinite sea of being underlying the waves of our finite selves. To the bhakta, for whom feelings are more real than thoughts, God appears different and more personal.

In bhakti, God must stand distinct from the worshipper, because only then he would know the joyful love of God. He doesn’t want to be one with God. Thus, the bhakta’s goal differs from the jnani’s. He strives not to identify with God, but to adore God with every element of his or her being. God to him is a person who possesses attributes. He loves God dearly for love’s sake alone. He has no selfish motive of getting something in return. This serves to weaken the world’s grip.

It is difficult to love a Being who can neither be seen nor heard. Hinduism, therefore, provides hundreds of myths and images of God. But this is neither idolatry nor polytheism because the bhakta is aware of his limitation in visualizing a God who is omnipresent, without form, and needs no praise. Parables and legends present ideals in ways that make hearers long to embody them. The value of these things lies in their power to recall our minds from the world’s distractions to the thought of God and God’s love.

A feature of bhakti yoga is Japam, which is the practice of repeating God’s name. Washing or weaving, planting or shopping, imperceptibly but indelibly these verbal droplets of aspiration soak down into the subconscious, loading it with the divine. The fact that love assumes different nuances according to the relationship involved, is also put to religious use. Hinduism holds that all of these modes have their place in strengthening the love of God and encourages bhaktas to make use of them all. Lastly, a Hindu worships God in the form of his chosen ideal. God is represented in innumerable forms. Each is but a symbol that points to something beyond; and as none exhausts God’s actual nature, the entire array is needed to complete the picture of God’s aspects and manifestations. But though the representations point equally to God, it is advisable for each devotee to form a lifelong attachment to one of them. Only so can its meaning deepen and its full power become accessible.

God is the belief in Hinduism that, ultimately, good will prevail.

.

Comments

We ultimately acquire those ideals that we ardently long for, no longer identifying ourselves with the mundane. Single-mindedly pursuing our ideals with devotion is the path of love.

.

Original Text

The yoga of knowledge is said to be the shortest path to divine realization. It is also the steepest. Requiring as it does a rare combination of rationality and spirituality, it is for a select few.

By and large, life is powered less by reason than by emotion; and of the many emotions that crowd the human heart, the strongest is love. Even hate can be interpreted as a rebound from the thwarting of this impulse. Moreover, people tend to become like that which they love, with its name written on their brows. The aim of bhakti yoga is to direct toward God the love that lies at the base of every heart. “As the waters of the Ganges flow incessantly toward the ocean,” says God in the Bhagavata Purana,, “so do the minds of the bhakta move constantly toward Me, the Supreme Person residing in every heart, immediately they hear about My qualities.”

In contrast to the way of knowledge, bhakti yoga has countless followers, being, indeed, the most popular of the four. Though it originated in antiquity, one of its best-known proponents was a sixteenth-century mystical poet named Tulsidas. During his early married life he was inordinately fond of his wife, to the point that he could not abide her absence even for a day. One day she went to visit her parents. Before the day was half over, Tulsidas turned up at her side, whereupon his wife exclaimed, “How passionately attached to me you are! If only you could shift your attachment to God, you would reach him in no time.” “So I would,” thought Tulsidas. He tried it, and it worked.

All the basic principles of bhakti yoga are richly exemplified in Christianity. Indeed, from the Hindu point of view, Christianity is one great brilliantly lit bhakti highway toward God, other paths being not neglected, but less clearly marked. On this path God is conceived differently than in jnana. In jnana yoga the guiding image was of an infinite sea of being underlying the waves of our finite selves. This sea typified the all-pervading Self, which is as much within us as without, and with which we should seek to identify. Thus envisioned, God is impersonal, or rather transpersonal, for personality, being something definite, seems to be finite whereas the jnanic Godhead is infinite. To the bhakti, for whom feelings are more real than thoughts, God appears different on each of these counts.

First, as healthy love is out-going, the bhakta will reject all suggestions that the God one loves is oneself, even one’s deepest Self, and insist on God’s otherness. As a Hindu devotional classic puts the point, “I want to taste sugar; I don’t want to be sugar.”

Can water quaff itself?

Can trees taste of the fruit they bear?

He who worships God must stand distinct from Him,

So only shall he know the joyful love of God;

For if he say that God and he are one,

That joy, that love, shall vanish instantly away.

Pray no more for utter oneness with God:

Where were the beauty if jewel and setting were one?

The heat and the shade are two,

If not, where were the comfort of shade?

Mother and child are two,

If not, where were the love?

When after being sundered, they meet,

What joy do they feel, the mother and child!

Where were joy, if the two were one?

Pray, then, no more for utter oneness with God.

Second, being persuaded of God’s otherness, the bhakta’s goal, too, will differ from the jnani’s. The bhakta will strive not to identify with God, but to adore God with every element of his or her being. The words of Bede Frost, though written in another tradition, are directly applicable to this side of Hinduism: “The union is no Pantheist absorption of the man in the one, but is essentially personal in character. More, since it is preeminently a union of love, the kind of knowledge which is required is that of friendship in the very highest sense of the word.” Finally, in such a context God’s personality, far from being a limitation, is indispensable. Philosophers may be able to love pure being, infinite beyond all attributes, but they are exceptions. The normal object of human love is a person who possesses attributes.

All we have to do in this yoga is to love God dearly—not just claim such love, but love God in fact; love God only (other things being loved in relation to God); and love God for no ulterior reason (not even from the desire for liberation, or to be loved in return) but for love’s sake alone. Insofar as we succeed in this we know joy, for no experience can compare with that of being fully and authentically in love. Moreover, every strengthening of our affections toward God will weaken the world’s grip. Saints may, indeed will, love the world more than do the profane; but they will love it in a very different way, seeing in it the reflected glory of the God they adore.

How is such love to be engendered? Obviously, the task will not be easy. The things of this world clamor for our affection so incessantly that it may be marveled that a Being who can neither be seen nor heard can ever become their rival.

Enter Hinduism’s myths, her magnificent symbols, her several hundred images of God, her rituals that keep turning night and day like never-ending prayer wheels. Valued as ends in themselves these could, of course, usurp God’s place, but this is not their intent. They are matchmakers whose vocation is to introduce the human heart to what they represent but themselves are not. It is obtuse to confuse Hinduism’s images with idolatry, and their multiplicity with polytheism. They are runways from which the sense-laden human spirit can rise for its “flight of the alone to the Alone.” Even village priests will frequently open their temple ceremonies with the following beloved invocation:

O Lord, forgive three sins that are due to my human limitations:

Thou art everywhere, but I worship you here;

Thou art without form, but I worship you in these forms;

Thou needest no praise, yet I offer you these prayers and salutations.

Lord, forgive three sins that are due to my human limitations.

A symbol such as a multi-armed image, graphically portraying God’s astounding versatility and superhuman might, can epitomize an entire theology. Myths plumb depths that the intellect can see only obliquely. Parables and legends present ideals in ways that make hearers long to embody them—vivid support for Irwin Edman’s contention that “it is a myth, not a mandate, a fable, not a logic by which people are moved.” The value of these things lies in their power to recall our minds from the world’s distractions to the thought of God and God’s love. In singing God’s praises, in praying to God with wholehearted devotion, in meditating on God’s majesty and glory, in reading about God in the scriptures, in regarding the entire universe as God’s handiwork, we move our affections steadily in God’s direction. “Those who meditate on Me and worship Me without any attachment to anything else,” says Lord Krishna in the Bhagavad-Gita, “those I soon lift from the ocean of death.”

Three features of the bhakta’s approach deserve mention: japam, ringing the changes on love, and the worship of one’s chosen ideal.

Japam is the practice of repeating God’s name. It finds a Christian parallel in one of the classics of Russian spirituality, The Way of a Pilgrim. This is the story of an unnamed peasant whose first concern is to fulfill the biblical injunction to “pray without ceasing.” Seeking for someone who can explain how it is possible to do this, he wanders through Russia and Siberia with a knapsack of dried bread for food and the charity of locals for shelter, consulting many authorities, only to be disappointed until at last he meets an old man who teaches him “a constant, uninterrupted calling upon the divine Name of Jesus with the lips, in the spirit, in the heart, during every occupation, at all times, in all places, even during sleep.” The pilgrim’s teacher trains him until he can repeat the name of Jesus more than 12,000 times a day without strain. This frequent service of the lips imperceptibly becomes a genuine appeal of the heart. The prayer becomes a constant, warming presence within him that brings a bubbling joy. “Keep the name of the Lord spinning in the midst of all your activities” is a Hindu statement of the same point. Washing or weaving, planting or shopping, imperceptibly but indelibly these verbal droplets of aspiration soak down into the subconscious, loading it with the divine.

Ringing the changes on love puts to religious use the fact that love assumes different nuances according to the relationship involved. The love of the parent for the child carries overtones of protectiveness, whereas a child’s love includes dependence. The love of friends is different from the conjugal love of woman and man. Different still is the love of a devoted servant for its master. Hinduism holds that all of these modes have their place in strengthening the love of God and encourages bhaktas to make use of them all. In practice Christianity does the same. Most frequently it envisions God as benevolent protector, symbolized as lord or parent, but other modes are not absent. “What a Friend we have in Jesus” is a familiar Christian hymn, and “my Master and my Friend” figures prominently in another Christian favorite. God figures as spouse in the Song of Songs and in Christian mystical writings where the marriage of the soul to Christ is a standing metaphor. The attitude of regarding God as one’s child sounds somewhat foreign to Western ears, yet much of the magic of Christmas derives from this being the one time in the year when God enters the heart as a child, eliciting thereby the tenderness of the parental instinct.

We come finally to the worship of God in the form of one’s chosen ideal. The Hindus have represented God in innumerable forms. This, they say, is appropriate. Each is but a symbol that points to something beyond; and as none exhausts God’s actual nature, the entire array is needed to complete the picture of God’s aspects and manifestations. But though the representations point equally to God, it is advisable for each devotee to form a lifelong attachment to one of them. Only so can its meaning deepen and its full power become accessible. The representation selected will be one’s ishta, or adopted form of the divine. The bhakta need not shun other forms, but this one will never be displaced and will always enjoy a special place in its disciple’s heart. The ideal form for most people will be one of God’s incarnations, for God can be loved most readily in human form because our hearts are already attuned to loving people. Many Hindus acknowledge Christ as a God-man, while believing that there have been others, such as Rama, Krishna, and the Buddha. Whenever the stability of the world is seriously threatened, God descends to redress the imbalance.

When goodness grows weak,

When evil increases,

I make myself a body.

In every age I come back

To deliver the holy,

To destroy the sin of the sinner,

To establish the righteous. (Bhagavad-Gita, IV:7–8)

.