Reference: SC: Psychology

NOTE: Text in color contains Vinaire’s comments.

.

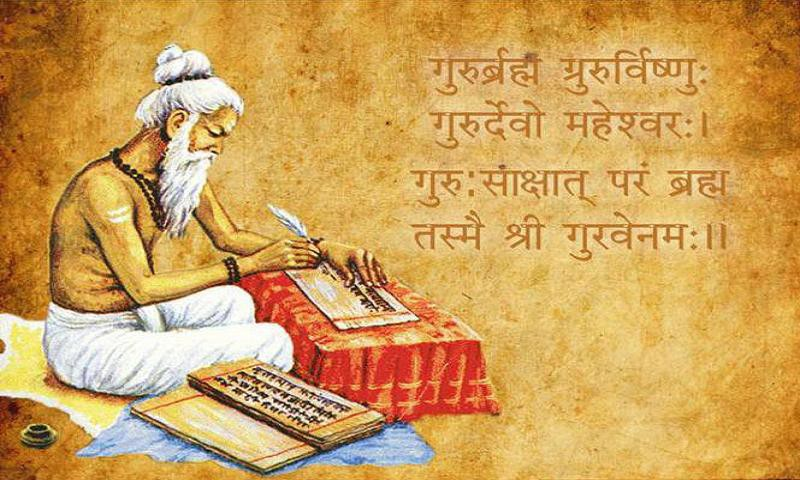

Ontological Assumptions

Western and Eastern traditions diverged fundamentally in their conceptualization of self and consciousness. Western thought, particularly after Descartes, increasingly adopted substance dualism, treating mind and body as distinct entities requiring connection. Eastern traditions maintained holistic monism, viewing psyche as inherently embodied and integrated with physical and spiritual dimensions.

.

Methodological Approaches

The West progressively prioritized empirical observation and rational analysis, with Vives’s inductive methods and Enlightenment experimentalism establishing psychology’s scientific trajectory. Eastern approaches emphasized introspection, meditative practice, and holistic observation, with Indian yoga and Chinese dialectical analysis providing systematic introspective methodologies.

.

Emotion Theory

Medieval Western thought treated emotions as physiological-psychological responses requiring rational direction. Islamic psychology similarly viewed emotions as natural responses needing cultivation through virtue ethics. Indian psychology identified emotions as expressions of manas and hrdaya, requiring equanimity rather than control. Chinese philosophy developed polarity theories, understanding emotions as manifestations of qing requiring balance between Confucian cultivation and Taoist naturalness.

.

Mental Illness Treatment

Western approaches evolved from supernatural explanations toward medical models, with compassionate care replacing harsh treatment by the 18th century. Islamic psychology maintained holistic treatment combining physical, psychological, and spiritual interventions throughout the period. Indian and Chinese traditions developed sophisticated psychotherapeutic techniques emphasizing meditation, lifestyle modification, and restoration of balance.

.

Consciousness Studies

Western consciousness theory progressed from Ockham’s intuitive cognition to Descartes’s cogito, emphasizing self-awareness as rational certainty. Eastern traditions explored altered states (Indian turiya, Buddhist jhānas) and developed detailed cartographies of consciousness levels, with Islamic mystics (Sufis) mapping spiritual stations (maqāmāt) of self-transformation.

.

Conclusion

The 11th–18th centuries established foundational frameworks that continue shaping contemporary psychology. Western development demonstrated increasing methodological rigor and scientific orientation, moving from theological to naturalistic explanations. Eastern traditions maintained holistic integration, developing sophisticated wellness models that modern psychology has only recently begun to appreciate. The period’s most enduring contribution may be the diversity of psychological paradigms it produced—demonstrating that human consciousness can be understood through multiple valid frameworks, each offering distinctive insights into the complex relationship between mind, body, and society.

This comparative history reveals that psychology’s “progress” is not linear but multidimensional, with different civilizations developing complementary approaches to understanding human nature. The 18th century’s synthesis of empirical method and holistic concern prefigured psychology’s ongoing integration of biological, psychological, and social dimensions—a reconciliation of insights that Eastern traditions never divided.

The Western psychology focuses on individuality; whereas the Eastern psychology focuses on attaining universal consciousness. The contradiction between these two goals is seen in Scientology. This contradiction, however, is handled in Postulate Mechanics.

.