Reference: The Nature of the Physical World

This paper presents Chapter XV (section 1) from the book THE NATURE OF THE PHYSICAL WORLD by A. S. EDDINGTON. The contents of this book are based on the lectures that Eddington delivered at the University of Edinburgh in January to March 1927.

The paragraphs of original material are accompanied by brief comments in color, based on the present understanding. Feedback on these comments is appreciated.

The heading below links to the original materials.

.

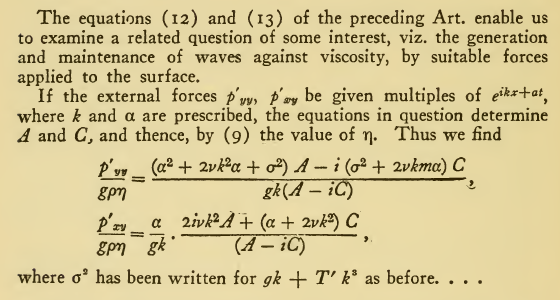

One day I happened to be occupied with the subject of “Generation of Waves by Wind”. I took down the standard treatise on hydrodynamics, and under that heading I read—

And so on for two pages. At the end it is made clear that a wind of less than half a mile an hour will leave the surface unruffled. At a mile an hour the surface is covered with minute corrugations due to capillary waves which decay immediately the disturbing cause ceases. At two miles an hour the gravity waves appear. As the author modestly concludes, “Our theoretical investigations give considerable insight into the incipient stages of wave-formation”.

On another occasion the same subject of “Generation of Waves by Wind” was in my mind; but this time another book was more appropriate, and I read—

There are waters blown by changing winds to laughter

And lit by the rich skies, all day. And after,

Frost, with a gesture, stays the waves that dance

And wandering loveliness. He leaves a white

Unbroken glory, a gathered radiance,

A width, a shining peace, under the night.

The magic words bring back the scene. Again we feel Nature drawing close to us, uniting with us, till we are filled with the gladness of the waves dancing in the sunshine, with the awe of the moonlight on the frozen lake. These were not moments when we fell below ourselves. We do not look back on them and say, “It was disgraceful for a man with six sober senses and a scientific understanding to let himself be deluded in that way. I will take Lamb’s Hydrodynamics with me next time”. It is good that there should be such moments for us. Life would be stunted and narrow if we could feel no significance in the world around us beyond that which can be weighed and measured with the tools of the physicist or described by the metrical symbols of the mathematician.

Of course it was an illusion. We can easily expose the rather clumsy trick that was played on us. Aethereal vibrations of various wave-lengths, reflected at different angles from the disturbed interface between air and water, reached our eyes, and by photoelectric action caused appropriate stimuli to travel along the optic nerves to a brain-centre. Here the mind set to work to weave an impression out of the stimuli. The incoming material was somewhat meagre; but the mind is a great storehouse of associations that could be used to clothe the skeleton. Having woven an impression the mind surveyed all that it had made and decided that it was very good. The critical faculty was lulled. We ceased to analyse and were conscious only of the impression as a whole. The warmth of the air, the scent of the grass, the gentle stir of the breeze, combined with the visual scene in one transcendent impression, around us and within us. Associations emerging from their storehouse grew bolder. Perhaps we recalled the phrase “rippling laughter”. Waves—ripples—laughter—gladness —the ideas jostled one another. Quite illogically we were glad; though what there can possibly be to be glad about in a set of aethereal vibrations no sensible person can explain. A mood of quiet joy suffused the whole impression. The gladness in ourselves was in Nature, in the waves, everywhere. That’s how it was.

The mind is capable of great imagination. The person is not being deceived as long as he aware that it is imagination.

It was an illusion. Then why toy with it longer? These airy fancies which the mind, when we do not keep it severely in order, projects into the external world should be of no concern to the earnest seeker after truth. Get back to the solid substance of things, to the material of the water moving under the pressure of the wind and the force of gravitation in obedience to the laws of hydrodynamics. But the solid substance of things is another illusion. It too is a fancy projected by the mind into the external world. We have chased the solid substance from the continuous liquid to the atom, from the atom to the electron, and there we have lost it. But at least, it will be said, we have reached something real at the end of the chase—the protons and electrons. Or if the new quantum theory condemns these images as too concrete and leaves us with no coherent images at all, at least we have symbolic co-ordinates and momenta and Hamiltonian functions devoting themselves with single-minded purpose to ensuring that qp—pq shall be equal to ih/2π.

After atom we have gotten only as far as the proton and electron; and mathematical functions and relationships.

In a previous chapter I have tried to show that by following this course we reach a cyclic scheme which from its very nature can only be a partial expression of our environment. It is not reality but the skeleton of reality. “Actuality” has been lost in the exigencies of the chase. Having first rejected the mind as a worker of illusion we have in the end to return to the mind and say, “Here are worlds well and truly built on a basis more secure than your fanciful illusions. But there is nothing to make any one of them an actual world. Please choose one and weave your fanciful images into it. That alone can make it actual”. We have torn away the mental fancies to get at the reality beneath, only to find that the reality of that which is beneath is bound up with its potentiality of awakening these fancies. It is because the mind, the weaver of illusion, is also the only guarantor of reality that reality is always to be sought at the base of illusion. Illusion is to reality as the smoke to the fire. I will not urge that hoary untruth “There is no smoke without fire”. But it is reasonable to inquire whether in the mystical illusions of man there is not a reflection of an underlying reality.

The knowledge obtained through science may be in the form of a cyclic scheme (tautology), but that cycle keeps on growing in detail. The difference between illusion and reality lies in the amount of anomalies present. The fewer anomalies there are the more real it is. Imagination is not opposite of reality. It has its place in reality as long as we recognize it for what it is, and resolve any anomalies present.

To put a plain question—Why should it be good for us to experience a state of self-deception such as I have described? I think everyone admits that it is good to have a spirit sensitive to the influences of Nature, good to exercise an appreciative imagination and not always to be remorselessly dissecting our environment after the manner of the mathematical physicists. And it is good not merely in a utilitarian sense, but in some purposive sense necessary to the fulfilment of the life that is given us. It is not a dope which it is expedient to take from time to time so that we may return with greater vigour to the more legitimate employment of the mind in scientific investigation. Just possibly it might be defended on the ground that it affords to the non-mathematical mind in some feeble measure that delight in the external world which would be more fully provided by an intimacy with its differential equations. (Lest it should be thought that I have intended to pillory hydrodynamics, I hasten to say in this connection that I would not rank the intellectual (scientific) appreciation on a lower plane than the mystical appreciation; and I know of passages written in mathematical symbols which in their sublimity might vie with Rupert Brooke’s sonnet.) But I think you will agree with me that it is impossible to allow that the one kind of appreciation can adequately fill the place of the other. Then how can it be deemed good if there is nothing in it but self-deception? That would be an upheaval of all our ideas of ethics. It seems to me that the only alternatives are either to count all such surrender to the mystical contact of Nature as mischievous and ethically wrong, or to admit that in these moods we catch something of the true relation of the world to ourselves—a relation not hinted at in a purely scientific analysis of its content. I think the most ardent materialist does not advocate, or at any rate does not practice, the first alternative; therefore I assume the second alternative, that there is some kind of truth at the base of the illusion.

In no way is the literary pursuit of imagination deceptive if it is understood for what it is. Using science is a reference point to judge is false.

But we must pause to consider the extent of the illusion. Is it a question of a small nugget of reality buried under a mountain of illusion? If that were so it would be our duty to rid our minds of some of the illusion at least, and try to know the truth in purer form. But I cannot think there is much amiss with our appreciation of the natural scene that so impresses us. I do not think a being more highly endowed than ourselves would prune away much of what we feel. It is not so much that the feeling itself is at fault as that our introspective examination of it wraps it in fanciful imagery. If I were to try to put into words the essential truth revealed in the mystic experience, it would be that our minds are not apart from the world; and the feelings that we have of gladness and melancholy and our yet deeper feelings are not of ourselves alone, but are glimpses of a reality transcending the narrow limits of our particular consciousness—that the harmony and beauty of the face of Nature is at root one with the gladness that transfigures the face of man. We try to express much the same truth when we say that the physical entities are only an extract of pointer readings and beneath them is a nature continuous with our own. But I do not willingly put it into words or subject it to introspection. We have seen how in the physical world the meaning is greatly changed when we contemplate it as surveyed from without instead of, as it essentially must be, from within. By introspection we drag out the truth for external survey; but in the mystical feeling the truth is apprehended from within and is, as it should be, a part of ourselves.

.