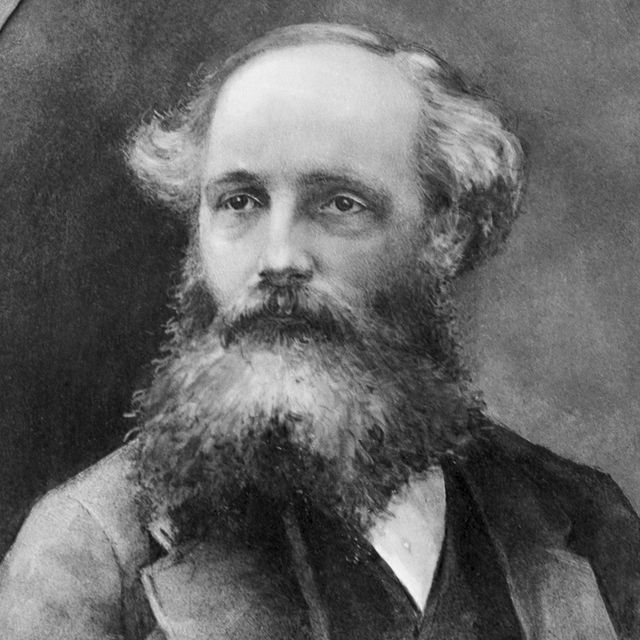

Maxwell in an article on ATOM written for the 9th edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica in 1875:

ATOM (ἄτομος) is a body which cannot be cut in two. The atomic theory is a theory of the constitution of bodies, which asserts that they are made up of atoms. The opposite theory is that of the homogeneity and continuity of bodies, and asserts, at least in the case of bodies having no apparent organisation, such, for instance, as water, that as we can divide a drop of water into two parts which are each of them drops of water, so we have reason to believe that these smaller drops can be divided again, and the theory goes on to assert that there is nothing in the nature of things to hinder this process of division from being repeated over and over again, times without end. This is the doctrine of the infinite divisibility of bodies, and it is in direct contradiction with the theory of atoms.

The atomists assert that after a certain number of such divisions the parts would be no longer divisible, because each of them would be an atom. The advocates of the continuity of matter assert that the smallest conceivable body has parts, and that whatever has parts may be divided.

In ancient times Democritus was the founder of the atomic theory, while Anaxagoras propounded that of continuity, under the name of the doctrine of homœomeria (Ὁμοιομέρια), or of the similarity of the parts of a body to the whole. The arguments of the atomists, and their replies to the objections of Anaxagoras, are to be found in Lucretius.

In modern times the study of nature has brought to light many properties of bodies which appear to depend on the magnitude and motions of their ultimate constituents, and the question of the existence of atoms has once more become conspicuous among scientific inquiries.

Today, we have a well-developed theory of atoms compared to the times of Maxwell. The erroneous assumption is that all substance is of the same consistency. The truth is that all substance is continuous yet it varies in consistency. Therefore, we have a spectrum of substance with increasing consistency. The upper end of this spectrum is found in the atom, whose nucleus consists of extremely dense substance. The lower part of the spectrum forms the space. It is this dense nucleus which makes atoms discrete. The very fact that we have dense material bodies existing in much lighter substance of space, provides support to the atomic theory.

We shall begin by stating the opposing doctrines of atoms and of continuity before giving an outline of the state of molecular science as it now exists. In the earliest times the most ancient philosophers whose speculations are known to us seem to have discussed the ideas of number and of continuous magnitude, of space and time, of matter and motion, with a native power of thought which has probably never been surpassed. Their actual knowledge, however, and their scientific experience were necessarily limited, because in their days the records of human thought were only beginning to accumulate. It is probable that the first exact notions of quantity were founded on the consideration of number. It is by the help of numbers that concrete quantities are practically measured and calculated. Now, number is discontinuous. We pass from one number to the next per saltum. The magnitudes, on the other hand, which we meet with in geometry, are essentially continuous. The attempt to apply numerical methods to the comparison of geometrical quantities led to the doctrine of incommensurables, and to that of the infinite divisibility of space. Meanwhile, the same considerations had not been applied to time, so that in the days of Zeno of Elea time was still regarded as made up of a finite number of ” moments,” while space was confessed to be divisible without limit. This was the state of opinion when the celebrated arguments against the possibility of motion, of which that of Achilles and the tortoise is a specimen, were propounded by Zeno, and such, apparently, continued to be the state of opinion till Aristotle pointed out that time is divisible without limit, in precisely the same sense that space is. And the slowness of the development of scientific ideas may be estimated from the fact that Bayle does not see any force in this statement of Aristotle, but continues to admire the paradox of Zeno. (Bayle’s Dictionary, art. “Zeno”). Thus the direction of true scientific progress was for many ages towards the, recognition of the infinite divisibility of space and time.

Space and time being infinitely divisible means that substance is infinitely divisible too as they are all related. The substance is continuous throughout its spectrum though its consistency changes. The continuity makes it infinitely divisible.

It was easy to attempt to apply similar arguments to matter. If matter is extended and fills space, the same mental operation by which we recognise the divisibility of space may be applied, in imagination at least, to the matter which occupies space. From this point of view the atomic doctrine might be regarded as a relic of the old numerical way of conceiving magnitude, and the opposite doctrine of the infinite divisibility of matter might appear for a time the most scientific. The atomists, on the other hand, asserted very strongly the distinction between matter and space. The atoms, they said, do not fill up the universe ; there are void spaces between them. If it were not so, Lucretius tells us, there could be no motion, for the atom which gives way first must have some empty place to move into.

“Quapropter locus est intactus, inane, vacansque

Quod si non esset, nulla ratione moveri

Res possent; namque, officium quod corporis exstat,

Officere atque obstare, id in omni tempore adesset

Omnibus : haud igitur quicquam procedere posset,

Principium quoniam cedendi nulla daret res.”—De Rerum Natura, i. 335.

The opposite school maintained then, as they have always done, that there is no vacuum that every part of space is full of matter, that there is a universal plenum, and that all motion is like that of a fish in the water, which yields in front of the fish because the fish leaves room for it behind.

“Cedere squamigeris latices nitentibus aiunt Lt liquidas aperire vias, quia post loca pisces Linquant, quo possint cedentes Cedere squamigeris latices nitentibus aiunt Lt liquidas aperire vias, quia post loca pisces Linquant, quo possint cedentes confluere undcc.” i. 373.

In modern times Descartes held that, as it is of the essence of matter to be extended in length, breadth, and thickness, so it is of the essence of extension to be occupied by matter, for extension cannot be an extension of nothing.

“Ac proinde si quceratur quid fiet, si Dcus auferat omne corpus quod in aliquo vase continetur, et nullum aliud in ablati locum venire pernuttat ? respondendum est, vasis latera sibi invicem hoc ipso fore contigua. Cum eiiini inter duo corpora nihil interjacet, necesse est ut se inutuo tangant, ac manifesto repugnat ut distent, sive ut inter ipsa sit distantia, et tamen ut ista distantia sit nibil ; quia omnis distantia est modus extensionis, et ideo sine substantia extensa esse non potest.” Principia, ii. 18.

This identification of extension with substance rung through the whole of Descartcs’s works, and it forms one of the ultimate foundations of the system of Spinoza. Descartes, consistently with this doctrine, denied the existence of atoms as parts of matter, which by their own nature are indivisible. He seems to admit, however, that the Deity might make certain particles of matter indivisible in this sense, that no creature should be able to divide them. These particles, however, would be still divisible by their own nature, because the Deity cannot diminish his own power, and therefore must retain his power of dividing them. Leibnitz, on the other hand, regarded his monad as the ultimate element of everything.

Space denotes the extent of substance. Time denotes the duration of substance. These definitions and the idea of the spectrum of substance of increasing consistency resolves all contradictions. Substance of high consistency appears as a discrete particle in the substance of low consistency, though the substance remains continuous at the boundary and throughout.

.

[Addition 1]

.

There are thus two modes of thinking about the constitution of bodies, which have had their adherents both in ancient and in modern times. They correspond to the two methods of regarding quantity the arithmetical and the geometrical. To the atomist the true method of estimating the quantity of matter in a body is to count the atoms in it. The void spaces between the atoms count for nothing. To those who identify matter with extension, the volume of space occupied by a body is the only measure of the quantity of matter in it.

Of the different forms of the atomic theory, that of Boscovich may be taken as an example of the purest monadism. According to Boscovich matter is made up of atoms. Each atom is an indivisible point, having position in space, capable of motion in a continuous path, and possessing a certain mass, whereby a certain amount of force is required to produce a given change of motion. Besides this the atom is endowed with potential force, that is to say, that any two atoms attract or repel each other with a force depending on their distance apart. The law of this force, for all distances greater than say the thousandth of an inch, is an attraction varying as the inverse square of the distance. For smaller distances the force is an attraction for one distance and a repulsion for another, according to some law not yet discovered. Boscovich himself, in order to obviate the possibility of two atoms ever being in the same place, asserts that the ultimate force is a repulsion which increases without limit as the distance diminishes without limit, so that two atoms can never coincide. But this seems an unwarrantable concession to the vulgar opinion that two bodies cannot co-exist in the same place. This opinion is deduced from our experience of the behaviour of bodies of sensible size, but we have no experimental evidence that two atoms may not sometimes coincide. For instance, if oxygen and hydrogen combine to form water, we have no experimental evidence that the molecule of oxygen is not in the very same place with the two molecules of hydrogen. Many persons cannot get rid of the opinion that all matter is extended in length, breadth, and depth. This is a prejudice of the same kind with the last, arising from our experience of bodies consisting of immense multitudes of atoms. The system of atoms, according to Boscovich, occupies a certain region of space in virtue of the forces acting between the component atoms of the system and any other atoms when brought near them. No other system of atoms can occupy the same region of space at the same time, because, before it could do so, the mutual action of the atoms would have caused a repulsion between the two systems insuperable by any force which we can command. Thus, a number of soldiers with firearms may occupy an extensive region to the exclusion of the enemy’s armies, though the space filled by their bodies is but small. In this way Boscovich explained the apparent extension of bodies consisting of atoms, each of which is devoid of extension. According to Boscovich’s theory, all action between bodies is action at a distance. There is no such thing in nature as actual contact between two bodies. When two bodies are said in ordinary language to be in contact, all that is meant is that they are so near together that the repulsion between the nearest pairs of atoms belonging to the two bodies is very great.

The above explanation of “contact” between two bodies essentially shows that force is the essential nature of matter. The experience of solidity is simply the experience of this force of repulsion at the contact. The explanation may also apply to two heavenly bodies. For example, the earth and moon definitely attract each other; but they arrive at a distance when they cannot approach any closer. There is a force of repulsion between them that keeps them sliding against each other at that distance.

Thus, in Boscovich’s theory, the atom has continuity of existence in time and space. At any instant of time it is at some point of space, and it is never in more than one place at a time. It passes from one place to another along a continuous path. It has a definite mass which cannot be increased or diminished. Atoms are endowed with the power of acting on one another by attraction or repulsion, the amount of the force depending on the distance between them. On the other hand, the atom itself has no parts or dimensions. In its geometrical aspect it is a mere geometrical point. It has no extension in space. It has not the so-called property of Impenetrability, for two atoms may exist in the same place. This we may regard as one extreme of the various opinions about the constitution of bodies.

An atom is more than a point because it is basically force that is centered at a point. This tells us that the atom of matter is basically a concentrated force that has a certain dimension. Mass denotes the concentration of this force. The atom maintains a stable form; and it cannot be penetrated beyond a certain point.

The opposite extreme, that of Anaxagoras the theory that bodies apparently homogeneous and continuous are so in reality is, in its extreme form, a theory incapable of development. To explain the properties of any substance by this theory is impossible. We can only admit the observed properties of such substance as ultimate facts. There is a certain stage, however, of scientific progress in which a method corresponding to this theory is of service. In hydrostatics, for instance, we define a fluid by means of one of its known properties, and from this definition we make the system of deductions which constitutes the science of hydrostatics. In this way the science of hydrostatics may be built upon an experimental basis, without any consideration of the constitution of a fluid as to whether it is molecular or continuous. In like manner, after the French mathematicians had attempted, with more or less ingenuity, to construct a theory of elastic solids from the hypothesis that they consist of atoms in equilibrium under the action of their mutual forces, Stokes and others showed that all the results of this hypothesis, so far at least as they agreed with facts, might be deduced from the postulate that elastic bodies exist, and from the hypothesis that the smallest portions into which we can divide them are sensibly homogeneous. In this way the principle of continuity, which is the basis of the method of Fluxions and the whole of modern mathematics, may bo applied to the analysis of problems connected with material bodies by assuming them, for the purpose of this analysis, to be homogeneous. All that is required to make the results applicable to the real case is that the smallest portions of the substance of which we take any notice shall be sensibly of the same kind. Thus, if a railway contractor has to make a tunnel through a hill of gravel, and if one cubic yard of the gravel is so like another cubic yard that for the purposes of the contract they may be taken as equivalent, then, in estimating the work required to remove the gravel from the tunnel, he may, without fear of error, make his calculations as if the gravel were a continuous substance. But if a worm has to make his way through the gravel, it makes the greatest possible difference to him whether he tries to push right against a piece of gravel, or directs his course through one of the intervals between the pieces; to him, therefore, the gravel is by no means a homogeneous and continuous substance.

In the same way, a theory that some particular substance, say water, is homogeneous and continuous may be a good, working theory up to a certain point, but may fail when we come to deal with quantities so minute or so attenuated that their heterogeneity of structure comes into prominence. Whether this heterogeneity of structure is or is not consistent with homogeneity and continuity of substance is another question.

The extreme form of the doctrine of continuity is that stated by Descartes, who maintains that the whole universe is equally full of matter, and that this matter is all of one kind, having no essential property besides that of extension. All the properties which we perceive in matter he reduces to its parts being movable among one another, and so capable of all the varieties which we can perceive to follow from the motion of its parts (Principia, ii. 23). Descartes’s own attempts to deduce the different qualities and actions of bodies in this way are not of much value. More than a century was required to invent methods of investigating the conditions of the motion of systems of bodies such as Descartes imagined. But the hydrodynamical discovery of Helmholtz that a vortex in a perfect liquid possesses certain permanent characteristics, has been applied by Sir W. Thomson to form a theory of vortex atoms in a homogeneous, incompressible, and frictionless liquid, to which we shall return at the proper time.

[To be continued…]

.