Reference: Islam

[NOTE: In color are Vinaire’s comments.]

The distinctive thing about Islam is not its ideal but the detailed prescriptions it sets forth for achieving it. In addition to being a spiritual guide, Islam is a legal compendium. Islam joins faith to politics, religion to society, inseparably. Westerners who define religion in terms of personal experience would never be understood by Muslims.

“O men! listen to my words and take them to heart! Know ye that every Muslim is a brother to every other Muslim, and that you are now one brotherhood.” These notable words, spoken by the Prophet during his “farewell pilgrimage” to Mecca shortly before his death, epitomize one of Islam’s loftiest ideals and strongest emphases. The intrusion of nationalism in the last two centuries has played havoc with this ideal on the political level, but on the communal level it has remained discernibly intact. “There is something in the religious culture of Islam which inspired, in even the humblest peasant or peddler, a dignity and a courtesy toward others never exceeded and rarely equalled in other civilizations,” a leading Islamicist has written.

A sense of brotherhood epitomize one of Islam’s loftiest ideals and strongest emphases, that has remained discernibly intact on the communal level if not political.

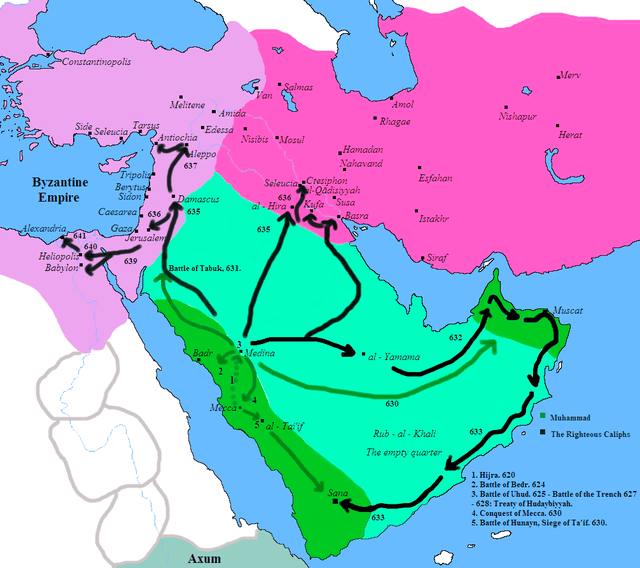

Looking at the difference between pre-and post-Islamic Arabia, we are forced to ask whether history has ever witnessed a comparable moral advance among so many people in so short a time. Before Muhammad there was virtually no restraint on intertribal violence. Glaring inequities in wealth and possession were accepted as the natural order of things. Women were regarded more as possessions than as human beings. Rather than say that a man could marry an unlimited number of wives, it would be more accurate to say that his relations with women were so casual that beyond the first wife or two they scarcely approximated marriage at all. Infanticide was common, especially of girls. Drunkenness and large-scale gambling have already been remarked upon. Within a half-century there was effected a remarkable change in the moral climate on all of these counts.

Looking at the difference between pre-and post-Islamic Arabia, we are forced to ask whether history has ever witnessed a comparable moral advance among so many people in so short a time.

Something that helped it to accomplish this near-miracle is a feature of Islam that we have already alluded to, namely its explicitness. Its basic objective in interpersonal relations, Muslims will say, is precisely that of Jesus and the other prophets: brotherly and sisterly love. The distinctive thing about Islam is not its ideal but the detailed prescriptions it sets forth for achieving it. We have already encountered its theory on this point. If Jesus had had a longer career, or if the Jews had not been so socially powerless at the time, Jesus might have systematized his teachings more. As it was, his work “was left unfinished. It was reserved for another Teacher to systematize the laws of morality.” The Koran is this later teacher. In addition to being a spiritual guide, it is a legal compendium. When its innumerable prescriptions are supplemented by the only slightly less authoritative hadith—traditions based on what Muhammad did or said on his own initiative—we are not surprised to find Islam the most socially explicit of the Semitic religions. Westerners who define religion in terms of personal experience would never be understood by Muslims, whose religion calls them to establish a specific kind of social order. Islam joins faith to politics, religion to society, inseparably.

The distinctive thing about Islam is not its ideal but the detailed prescriptions it sets forth for achieving it. In addition to being a spiritual guide, Islam is a legal compendium. Islam joins faith to politics, religion to society, inseparably. Westerners who define religion in terms of personal experience would never be understood by Muslims.

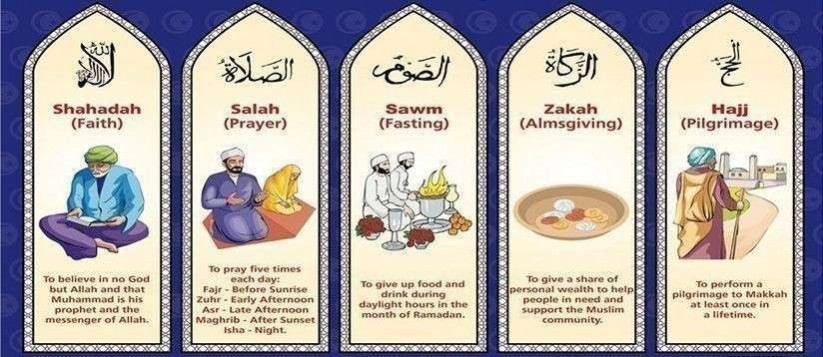

Islamic law is of enormous scope. It will be enough for our purposes if we summarize its provisions in four areas of collective life.

1. Economics. Islam is acutely aware of the physical foundations of life. Until bodily needs are met, higher concerns cannot flower. When one of Muhammad’s followers ran up to him crying, “My Mother is dead; what is the best alms I can give away for the good of her soul?” the Prophet, thinking of the heat of the desert, answered instantly, “Water! Dig a well for her, and give water to the thirsty.”

Islam is acutely aware of the physical foundations of life. Until bodily needs are met, higher concerns cannot flower.

Just as the health of an organism requires that nourishment be fed to its every segment, so too a society’s health requires that material goods be widely and appropriately distributed. These are the basic principles of Islamic economics, and nowhere do Islam’s democratic impulses speak with greater force and clarity. The Koran, supplemented by hadith, propounded measures that broke the barriers of economic caste and enormously reduced the injustices of special interest groups.

The Koran, supplemented by hadith, propounded measures that broke the barriers of economic caste and enormously reduced the injustices of special interest groups.

The model that animates Muslim economics is the body’s circulatory system. Health requires that blood flow freely and vigorously; sluggishness can bring on illness, blood clots occasion death. It is not different with the body politic, in which wealth takes the place of blood as the life-giving substance. As long as this analogy is honored and laws are in place to insure that wealth is in vigorous circulation, Islam does not object to the profit motive, economic competition, or entrepreneurial ventures—the more imaginative the latter, the better. So freely are these allowed that some have gone so far as to characterize the Koran as “a businessman’s book.” It does not discourage people from working harder than their neighbors, nor object to such people being rewarded with larger returns. It simply insists that acquisitiveness and competition be balanced by the fair play that “keeps arteries open,” and by compassion that is strong enough to pump life-giving blood—material resources—into the circulatory system’s smallest capillaries. These “capillaries” are fed by the Poor Due, which (as has been noted) stipulates that annually a portion of one’s holdings be distributed to the poor.

The model that animates Muslim economics is the body’s circulatory system. Just as the health of an organism requires that nourishment be fed to its every segment, so too a society’s health requires that material goods be widely and appropriately distributed.

As for the way to prevent “clotting,” the Koran went after the severest economic curse of the day—primogeniture—and flatly outlawed it. By restricting inheritance to the oldest son, this institution had concentrated wealth in a limited number of enormous estates. In banning the practice, the Koran sees to it that inheritance is shared by all heirs, daughters as well as sons. F. S. C. Northrop describes the settlement of a Muslim’s estate that he chanced to witness. The application of Islamic law that afternoon resulted in the division of some $53,000 among no less than seventy heirs.

In banning the practice of primogeniture, the Koran sees to it that inheritance is shared by all heirs, daughters as well as sons.

One verse in the Koran prohibits the taking of interest. At the time this was not only humane but eminently just, for loans were used then to tide the unfortunate over in times of disaster. With the rise of capitalism, however, money has taken on a new meaning. It now functions importantly as venture capital, and in this setting borrowed money multiplies. This benefits the borrower, and it is patently unjust to exclude the lender from his or her gain. The way Muslims have accommodated to this change is by making lenders in some way partners in the venture for which their monies are used. When capitalism is approached in this manner, Muslims find no incompatibility between its central feature, venture capital, and Islam. Capitalism’s excesses—which Muslims consider to be glaringly exhibited in the secular West—are another matter. The equalizing provisos of the Koran would, if duly applied, offset them.

Koran prohibits the taking of interest when loans are taken to tide the unfortunate over in times of disaster. When money is borrowed as venture capital then lenders are made partners in the venture in some way.

2. The Status of Women. Chiefly because it permits a plurality of wives, the West has accused Islam of degrading women.

If we approach the question historically, comparing the status of Arabian women before and after Muhammad, the charge is patently false. In the pre-Islamic “days of ignorance,” marriage arrangements were so loose as to be scarcely recognizable. Women were regarded as little more than chattel, to be done with as fathers or husbands pleased. Daughters had no inheritance rights and were often buried alive in their infancy.

Addressing conditions in which the very birth of a daughter was regarded as a calamity, the koranic reforms improved woman’s status incalculably. They forbade infanticide. They required that daughters be included in inheritance—not equally, it is true, but to half the proportion of sons, which seems just, in view of the fact that unlike sons, daughters would not assume financial responsibility for their households. In her rights as citizen—education, suffrage, and vocation—the Koran leaves open the possibility of woman’s full equality with man, an equality that is being approximated as the customs of Muslim nations become modernized. If in another century women under Islam do not attain the social position of their Western sisters, a position to which the latter have been brought by industrialism and democracy rather than religion, it will then be time, Muslims say, to hold Islam accountable.

Addressing conditions in which the very birth of a daughter was regarded as a calamity, the koranic reforms improved woman’s status incalculably. In her rights as citizen—education, suffrage, and vocation—the Koran leaves open the possibility of woman’s full equality with man.

It was in the institution of marriage, however, that Islam made its greatest contribution to women. It sanctified marriage, first, by making it the sole lawful locus of the sexual act. To the adherents of a religion in which the punishment for adultery is death by stoning and social dancing is proscribed, Western indictments of Islam as a lascivious religion sound ill-directed.

Islam sanctifies marriage by making it the sole lawful locus of the sexual act. The punishment for adultery is death by stoning.

Second, the Koran requires that a woman give her free consent before she may be wed; not even a sultan may marry without his bride’s express approval. Third, Islam tightened the wedding bond enormously. Though Muhammad did not forbid divorce, he countenanced it only as a last resort. Asserting repeatedly that nothing displeased God more than the disruption of marital vows, he instituted legal provisions to keep marriages intact. At the time of marriage husbands are required to provide the wife with a sum on which both agree and which she retains in its entirety should a divorce ensue. Divorce proceedings call for three distinct and separate periods, in each of which arbiters drawn from both families try to reconcile the two parties. Though such devices are intended to keep divorces to a minimum, wives no less than husbands are permitted to instigate them.

Koran requires that a woman give her free consent before she may be wed. It instituted legal provisions to keep marriages intact.

There remains, however, the issue of polygamy, or more precisely polygyny. It is true that the Koran permits a man to have up to four wives simultaneously, but there is a growing consensus that a careful reading of its regulations on the matter point toward monogamy as the ideal. Supporting this view is the Koran’s statement that “if you cannot deal equitably and justly with [more than one wife], you shall marry only one.” Other passages make it clear that “equality” here refers not only to material perquisites but to love and esteem. In physical arrangements each wife must have private quarters, and this in itself is a limiting factor. It is the second proviso, though—equality of love and esteem—that leads jurists to argue that the Koran virtually enjoins monogamy, for it is almost impossible to distribute affection and regard with exact equality. This interpretation has been in the Muslim picture since the third century of the Hijrah, and it is gaining increasing acceptance. To avoid any possible misunderstanding, many Muslims now insert in the marriage deed a clause by which the husband formally renounces his supposed right to a second concurrent spouse, and in point of fact—with the exception of African tribes where polygyny is customary—multiple wives are seldom found in Islam today.

It is true that the Koran permits a man to have up to four wives simultaneously, but there is a growing consensus that a careful reading of its regulations on the matter point toward monogamy as the ideal.

Nevertheless, the fact remains that the Koran does permit polygyny: “You may marry two, three, or four wives, but not more.” And what are we to make of Muhammad’s own multiple marriages? Muslims take both items as instances of Islam’s versatility in addressing diverse circumstances. There are circumstances in the imperfect condition we know as human existence when polygyny is morally preferable to its alternative. Individually, such a condition might arise if, early in marriage, the wife were to contract paralysis or another disability that would prevent sexual union. Collectively, a war that decimated the male population could provide an example, forcing (as this would) the option between polygyny and depriving a large proportion of women of motherhood and a nuclear family of any sort. Idealists may call for the exercise of heroic continence in such circumstances, but heroism is never a mass option. The actual choice is between a legalized polygyny in which sex is tightly joined to responsibility, and alternatively monogamy, which, being unrealistic, fosters prostitution, where men disclaim responsibility for their sexual partners and their progeny. Pressing their case, Muslims point out that multiple marriages are at least as common in the West; the difference is that they are successive. Is “serial polygyny,” the Western version, self-evidently superior to its coeval form, when women have the right to opt out of the arrangement (through divorce) if they want to? Finally, Muslims, though they have spoken frankly from the first of female sexual fulfillment as a marital right, do not skirt the volatile question of whether the male sexual drive is stronger than the female’s. “Hoggledy higamous, men are polygamous; /Higgledy hogamus, women monogamous,” Dorothy Parker wrote flippantly. If there is biological truth in her limerick, “rather than allowing this sensuality in the male to run riot, obeying nothing but its own impulses, the Law of Islam sets down a polygynous framework that provides a modicum of control. [It] confers a conscious mold on the formless instinct of man in order to keep him within the structures of religion.”

The actual choice is between a legalized polygyny in which sex is tightly joined to responsibility, and alternatively monogamy, which, being unrealistic, fosters prostitution, where men disclaim responsibility for their sexual partners and their progeny.

As for the veiling of women and their seclusion generally, the koranic injunction is restrained. It says only to “Tell your wives and your daughters and the women of the believers to draw their cloaks closely round them (when they go abroad). That will be better, so that they may be recognized and not annoyed” (33:59). Extremes that have evolved from this ruling are matters of local custom and are not religiously binding.

The veiling of women and their seclusion generally, the koranic injunction is restrained. Extremes that have evolved are matters of local custom and are not religiously binding.

Somewhere in this section on social issues the subject of penalties should be mentioned, for the impression is widespread that Islamic law imposes ones that are excessively harsh. This is a reasonable place to address this issue, for one of the most frequently cited examples is the punishment for adultery, which repeats the Jewish law of death by stoning—two others that are typically mentioned are severance of the thief’s hand, and flogging for a number of offenses. These stipulations are indeed severe, but (as Muslims see matters) this is to make the point that the injuries that occasion these penalties are likewise severe and will not be tolerated. Once this juridical point is in place, mercy moves in to temper the decrees. “Avert penalties by doubt,” Muhammad told his people, and Islamic jurisprudence legitimizes any stratagem that averts the penalty without outright impugning the Law. Stoning for adultery is made almost impossible by the proviso that four unimpeachable witnesses must have observed the act in detail. “Flogging” can be technically fulfilled by using a light sandal or even the hem of a garment, and thieves may retain their hands if the theft was from genuine need.

Islamic law imposes penalties that are excessively harsh; but this is to make the point that the injuries that occasion these penalties are likewise severe and will not be tolerated. Islamic jurisprudence legitimizes any stratagem that averts the penalty without outright impugning the Law.

3. Race Relations. Islam stresses racial equality and “has achieved a remarkable degree of interracial coexistence.” The ultimate test in this area is willingness to intermarry, and Muslims see Abraham as modeling this willingness in marrying Hagar, a black woman whom they regard as his second wife rather than a concubine. Under Elijah Muhammad the Black Muslim movement in America—it has had various names—was militant toward the whites; but when Malcolm X made his 1964 pilgrimage to Mecca, he discovered that racism had no precedent in Islam and could not be accommodated to it. Muslims like to recall that the first muezzin, Bilal, was an Ethiopian who prayed regularly for the conversion of the Koreish—“whites” who were persecuting the early believers, many of whom were black. The advances that Islam continues to make in Africa is not unrelated to this religion’s principled record on this issue.

Islam stresses racial equality and “has achieved a remarkable degree of interracial coexistence.”

4. The Use of Force. Muslims report that the standard Western stereotype that they encounter is that of a man marching with sword outstretched, followed by a long train of wives. Not surprisingly, inasmuch as from the beginning (a historian reports) Christians have believed that “the two most important aspects of Muhammad’s life…are his sexual licence and his use of force to establish religion.” Muslims feel that both Muhammad and the Koran have been maligned on these counts. License was discussed above. Here we turn to force.

Christians have believed that “the two most important aspects of Muhammad’s life…are his sexual licence and his use of force to establish religion.”

Admit, they say, that the Koran does not counsel turning the other cheek, or pacifism. It teaches forgiveness and the return of good for evil when the circumstances warrant—“turn away evil with that which is better” (42:37)—but this is different from not resisting evil. Far from requiring the Muslim to turn himself into a doormat for the ruthless, the Koran allows punishment of wanton wrongdoers to the full extent of the injury they impart (22:39–40). Justice requires this, they believe; abrogate reciprocity, which the principle of fair play requires, and morality descends to impractical idealism if not sheer sentimentality. Extend this principle of justice to collective life and we have as one instance jihad, the Muslim concept of a holy war, in which the martyrs who die are assured of heaven. All this the Muslim will affirm as integral to Islam, but we are still a far cry from the familiar charge that Islam spread primarily by the sword and was upheld by the sword.

The Koran does not counsel turning the other cheek. It allows punishment of wanton wrongdoers to the full extent of the injury they impart. The downside of this is that this becomes dangerous when one’s judgment is incorrect.

As an outstanding general, Muhammad left many traditions regarding the decent conduct of war. Agreements are to be honored and treachery avoided; the wounded are not to be mutilated, nor the dead disfigured. Women, children, and the old are to be spared, as are orchards, crops, and sacred objects. These, however, are not the point. The important question is the definition of a righteous war. According to prevailing interpretations of the Koran, a righteous war must either be defensive or to right a wrong. “Defend yourself against your enemies, but do not attack them first: God hates the aggressor” (2:190). The aggressive and unrelenting hostility of the idolaters forced Muhammad to seize the sword in self-defense, or, together with his entire community and his God-entrusted faith, be wiped from the face of the earth. That other teachers succumbed under force and became martyrs was to Muhammad no reason that he should do the same. Having seized the sword in self-defense he held onto it to the end. This much Muslims acknowledge; but they insist that while Islam has at times spread by the sword, it has mostly spread by persuasion and example.

The important question is the definition of a righteous war. According to prevailing interpretations of the Koran, a righteous war must either be defensive or to right a wrong. Again, the correctness of judgment becomes crucial.

The crucial verses in the Koran bearing on conversion read as follows:

Let there be no compulsion in religion (2:257).

To every one have We given a law and a way…. And if God had pleased, he would have made [all humankind] one people [people of one religion]. But he hath done otherwise, that He might try you in that which He hath severally given unto you: wherefore press forward in good works. Unto God shall ye return, and He will tell you that concerning which ye disagree (5:48).

There should be no compulsion in religion.

Muslims point out that Muhammad incorporated into his charter for Medina the principle of religious toleration that these verses announce. They regard that document as the first charter of freedom of conscience in human history and the authoritative model for those of every subsequent Muslim state. It decreed that “the Jews who attach themselves to our commonwealth [similar rights were later mentioned for Christians, these two being the only non-Muslim religions on the scene] shall be protected from all insults and vexations; they shall have an equal right with our own people to our assistance and good offices: the Jews…and all others domiciled in Yathrib, shall…practice their religion as freely as the Muslims.” Even conquered nations were permitted freedom of worship contingent only on the payment of a special tax in lieu of the Poor Due, from which they were exempt; thereafter every interference with their liberty of conscience was regarded as a direct contravention of Islamic law. If clearer indication than this of Islam’s stand on religious tolerance be asked, we have the direct words of Muhammad: “Will you then force men to believe when belief can come only from God?” Once, when a deputy of Christians visited him, Muhammad invited them to conduct their service in his mosque, adding, “It is a place consecrated to God.”

Muhammad incorporated into his charter for Medina the principle of religious toleration that these verses announce.

This much for theory and Muhammad’s personal example. How well Muslims have lived up to his principles of toleration is a question of history that is far too complex to admit of a simple, objective, and definitive answer. On the positive side Muslims point to the long centuries during which, in India, Spain, and the Near East, Christians, Jews, and Hindus lived quietly and in freedom under Muslim rule. Even under the worst rulers Christians and Jews held positions of influence and in general retained their religious freedom. It was Christians, not Muslims, we are reminded, who in the fifteenth century expelled the Jews from Spain where, under Islamic rule, they had enjoyed one of their golden ages. To press this example, Spain and Anatolia changed hands at about the same time—Christians expelled the Moors from Spain, while Muslims conquered what is now Turkey. Every Muslim was driven from Spain, put to the sword, or forced to convert, whereas the seat of the Eastern Orthodox church remains in Istanbul to this day. Indeed, if comparisons are what we want, Muslims consider Christianity’s record as the darker of the two. Who was it, they ask, who preached the Crusades in the name of the Prince of Peace? Who instituted the Inquisition, invented the rack and the stake as instruments of religion, and plunged Europe into its devastating wars of religion? Objective historians are of one mind in their verdict that, to put the matter minimally, Islam’s record on the use of force is no darker than that of Christianity.

It is a matter of history that Muslims and Christians have not lived up to the principles of their religions. Objective historians are of one mind in their verdict that, to put the matter minimally, Islam’s record on the use of force is no darker than that of Christianity.

Laying aside comparisons, Muslims admit that their own record respecting force is not exemplary. Every religion at some stages in its career has been used by its professed adherents to mask aggression, and Islam is no exception. Time and again it has provided designing chieftains, caliphs, and now heads of state with pretexts for gratifying their ambitions. What Muslims deny can be summarized in three points.

First, they deny that Islam’s record of intolerance and aggression is greater than that of the other major religions. (Buddhism may be an exception here.)

Second, they deny that Western histories are fair to Islam in their accounts of its use of force. Jihad, they say, is a case in point. To Westerners it conjures scenes of screaming fanatics being egged into war by promises that they will be instantly transported to heaven if they are slain. In actuality: (a) jihad literally means exertion, though because war requires exertion in exceptional degree the word is often, by extension, attached thereto. (b) The definition of a holy war in Islam is virtually identical with that of a just war in Christianity, where too it is sometimes called a holy war. (c) Christianity, too, considers those who die in such wars to be martyrs, and promises them salvation. (d) A hadith (canonical saying) of Muhammad ranks the battle against evil within one’s own heart above battles against external enemies. “We have returned from the lesser jihad,” the Prophet observed, following an encounter with the Meccans, “to face the greater jihad,” the battle with the enemy within oneself.

Third, Muslims deny that the blots in their record should be charged against their religion whose presiding ideal they affirm in their standard greeting, as-salamu ’alaykum (“Peace be upon you”).

Most followers do not adhere to their religion exactly. They always find excuses and loopholes for their errant behavior. This applies to Islam too.

.