Reference: Christianity

[NOTE: In color are Vinaire’s comments.]

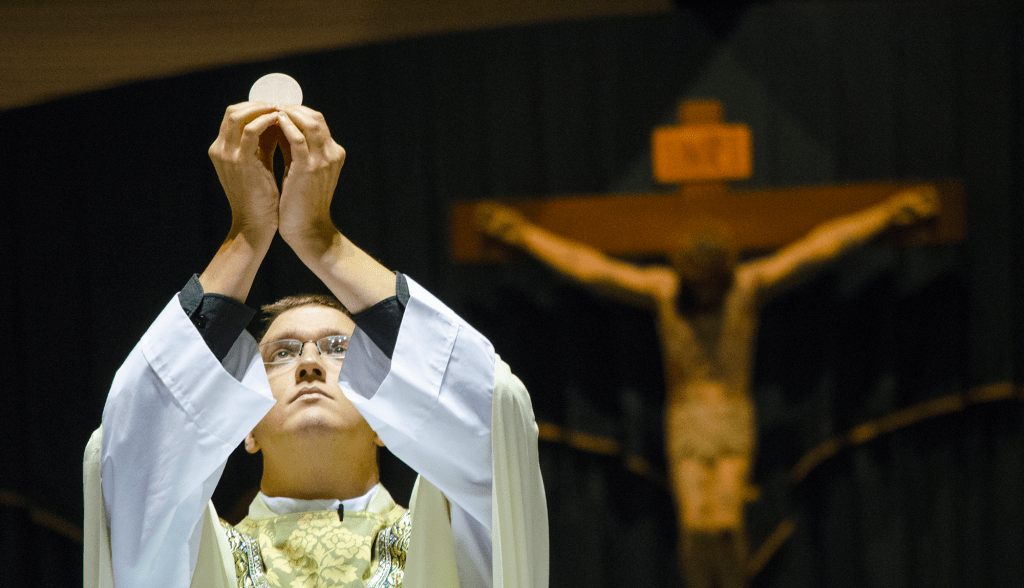

Catholics see Christ as having explicitly joined the sacramental agency of the Church to its teaching authority in his closing commission to his disciples.

We have been speaking of Christianity as a whole. This does not mean that every Christian will agree with all that has been said. Christianity is such a complex phenomenon that it is difficult to say anything significant about it that will carry the assent of all Christians. So it must be stressed that what has gone before is an interpretation. Nevertheless, it has sought to be an interpretation of the points that, substantially at least, Christians hold in common.

Christianity has become very complex with many different interpretations.

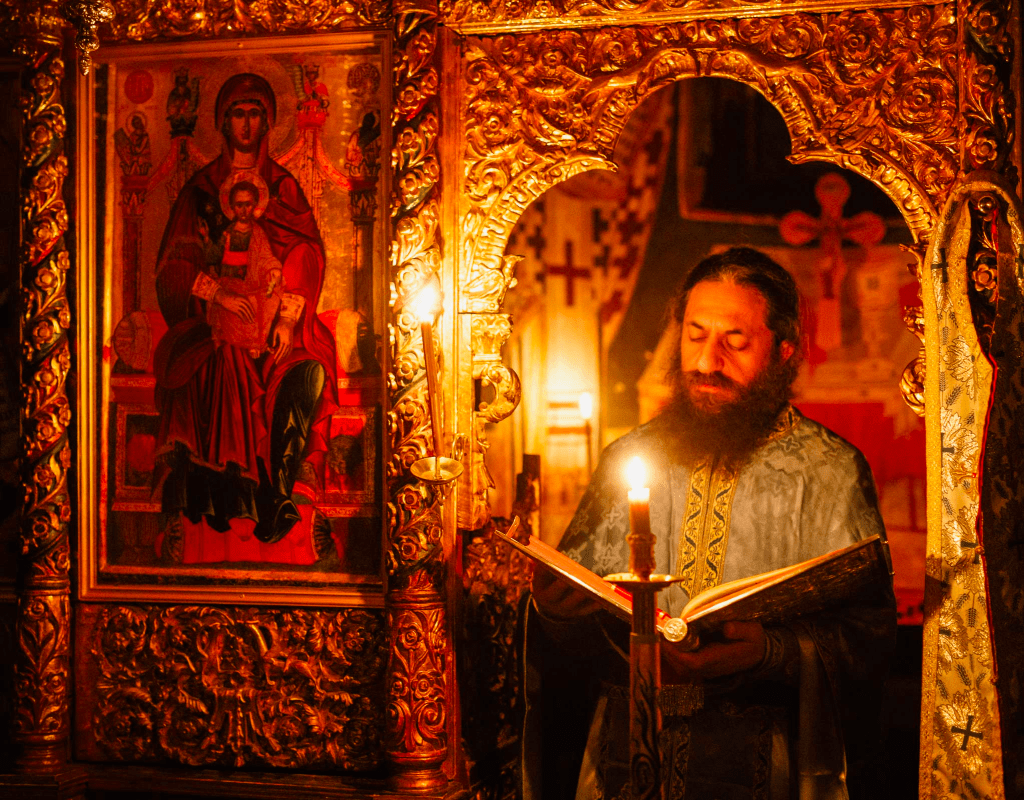

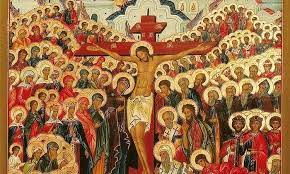

When we turn from the early Christianity we have been considering thus far to Christendom today, we find the Church divided into three great branches. Roman Catholicism focuses in the Vatican in Rome and spreads from there, being dominant, on the whole, through central and southern Europe, Ireland, and South America. Eastern Orthodoxy has its major influence in Greece, the Slavic countries, and the Soviet Union. Protestantism dominates Northern Europe, England, Scotland, and North America.

Today’s Christianity is divided into three main branches: Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Protestantism.

Up to 313 the Church struggled in the face of official Roman persecution. In that year it became legally recognized and enjoyed equal rights with other religions of the empire. Before the century was out, in 380, it became the official religion of the Roman Empire. With a few minor splinterings, such as the Nestorians, it continued as a united body up to 1054. This means that for roughly half its history the Church remained substantially one institution. In 1054, however, its first great division occurred, between the Eastern Orthodox Church in the East and the Roman Catholic Church in the West. The reasons for the break were complex—geography, culture, language, and politics as well as religion were involved—but it is not our concern to detail them here. Instead we move to the next great division, which occurred in the Western Church with the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century. Protestantism follows four main courses—Baptist, Lutheran, Calvinists, and Anglican—which themselves subdivide until the current census lists over 900 denominations in the United States alone. Currently, the ecumenical movement is bringing some of these denominations back together again. With these minimum facts at our disposal, we can proceed to our real concern, which is to try to understand the central perspectives of Christendom’s three great branches. Beginning with the Roman Catholic Church, we shall confine ourselves to what are perhaps the two most important concepts for the understanding of this branch of Christendom: the Church as teaching authority, and the Church as sacramental agent.

First Christianity came to be recognized as one of the religions. Then it became THE religion under one administration. Then it split into Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy based on cultural and geographical factors. In the West, Protestantism splintered off Roman Catholicism in big way. Then Protestantism came to be divided into four main courses and over 900 denominations.

The Church as Teaching Authority. First, the Church as teaching authority. This concept begins with the premise that God came to earth in the person of Jesus Christ to teach people the way to salvation—how they should live in this world so as to inherit eternal life in the next. If this is true, if his teachings really are the door to salvation and if the opening of this door was one of the prime reasons why he came to earth, it seems unlikely that he would have held this door ajar for his generation only. Would he not want his saving teachings to continue to be available to the world?

An important aspect of the Roman Catholic Church is being a teaching authority. It teaches how to achieve eternal life in the next world. The anomaly is that why God has not appeared again and again in other generations and other places to bring his teachings to the whole world.

The reader might agree but add, “Do we not have his teachings—in the Bible?” This, however, raises the question of interpretation. The Constitution of the United States is a reasonably unambiguous document, but our social life would be chaos without an authority, the Supreme Court, to interpret it. Equally with the Bible. Leave it to private interpretation and whirlwind is the sure harvest. Unguided by the Church as teaching authority, Bible study is certain to lead different students to different conclusions, even on subjects of the highest moment. And since the net effect of proposing alternative answers to the same question is to make it impossible to believe any answer confidently, this approach would reduce the Christian faith to hesitation and stammer.

The Roman Catholic Church acts to interpret the teachings in the Bible. Otherwise, there will be different interpretations and chaos in the Christian world.

Let us take a specific issue for illustration. Is divorce moral? Surely, on a question as important as this, any religion that proposes to guide the conscience of its members may be expected to have a definite view. But suppose we try to draw that view directly from the Bible? Mark 10:11 tells us that “Whoever divorces his wife and marries another commits adultery.” Luke 16:18 concurs. But Matthew 5:32 enters a reservation: “except on the ground of unchastity.” What is the Christian to think? What are the probabilities that the Matthew text has been tampered with? May an unwronged party remarry or not?

There are different teachings in the Bible that give rise to doubt in important matters; for example, on the subject of divorce being moral. It makes one wonder if certain texts in the Bible has been tampered with.

The question is only a sample of the many that must remain forever in doubt if our only guides are the Bible and private conscience. Was Christ born of a virgin? Did his body ascend after death? Is the fourth Gospel authentic? Without a sure court of appeal, moral and theological disintegration seem inevitable. It was precisely to avert such disintegration that Christ established the Church to be his continuing representative on earth, that there might be one completely competent authority to adjudicate between truth and error on life-and-death matters. Only so could the “dead letter” of scripture be continually revivified by the living instinct of God’s own person. This is the meaning of the words, attributed to Jesus, “I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my Church…. I will give you the keys of the Kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven” (Matthew 16:18–19).

Christ established the Church to be his continuing representative on earth, that there might be one completely competent authority to adjudicate between truth and error on life-and-death matters.

Ultimately, this idea of the Church as teaching authority shapes the idea of papal infallibility. Every nation has its ruler, be he emperor, king, or president. The earthly head of the Church is the pope, successor to St. Peter in the bishopric of Rome. The doctrine of papal infallibility asserts that when the pope speaks officially on matters of faith or morals, God stays him against error.

Ultimately, this idea of the Church as teaching authority shapes the idea of papal infallibility. God stays the pope against error.

This doctrine is so often misunderstood that we must emphasize that infallibility is a strictly limited gift. It does not assert that the pope is endowed with extraordinary intelligence. It does not mean that God helps him to know the answer to every conceivable question. Emphatically, it does not mean that Catholics have to accept the pope’s view on politics. The pope can make mistakes. He can fall into sin. The scientific or historical opinions he holds may be mistaken. He may write books that contain errors. Only in two limited spheres, faith and morals, is he infallible, and in these only when he speaks officially as the supreme teacher and lawgiver of the Church, defining a doctrine that should be held by all its members. When, after studying a problem that relates to faith or morals as carefully as possible and with all available help from expert consultants, he emerges with the Church’s answer—on these rare occasions it is not strictly speaking an answer, it is the answer. For on such occasions the Holy Spirit protects him from the possibility of error. These answers constitute the infallible teachings of the Church and as such are binding on Roman Catholics.

But pope’s infallibility is limited to the spheres of faith and morals, only when he speaks officially as the supreme teacher and lawgiver of the Church, defining a doctrine that should be held by all its members. The Holy Spirit protects the pope from the possibility of error.

The Church as Sacramental Agent. The second idea central to Roman Catholicism is the idea of the Church as sacramental agent. This supplements the idea of the Church as teaching authority. It is one thing to know what we should do; it is quite another to be able to do it, which is why there is a need for the Sacraments. The Church helps with both problems. It points the way in which we should live, and empowers us to live accordingly.

The second idea central to Roman Catholicism is the idea of the Church as sacramental agent.

The second gift is as important as the first. Christ called his followers to live lives far above the average in charity and service. No one would claim that this is easy. The Catholic, however, insists that we have not faced our situation squarely until we realize that without help such a life is impossible. For the life to which Christ called people is supernatural in the exact sense of being contrary to the pull of natural human instincts. By their own efforts people can no more live above human nature than an elephant can live a life of reason. Help, therefore, is needed. The Church, as God’s representative on earth, is the agency to provide it, and the Sacraments its means for doing so.

Sacraments are the means through which the Church enables its members to live a life of charity and service as called for by Christ.

Since the twelfth century the number of Sacraments in the Roman Catholic Church has been fixed at seven. In a striking way these parallel the great moments and needs of human life. People are born, they come of age, they marry or dedicate themselves completely to some life-purpose, and they die. Meanwhile, they must be reintegrated into society when they deviate, and they must eat. The Sacraments provide the spiritual counterparts of these natural events. As birth brings a child into the natural world, Baptism (by planting God’s first special grace in its soul) draws the infant into the supernatural order of existence. When the child reaches the age of reason and needs to be strengthened for mature reflection and responsible action, it is Confirmed. Usually, there comes a solemn moment during which an adult is joined to a human companion in Holy Matrimony, or dedicates his or her life entirely to God in Holy Orders. At life’s close the Sacrament of the Sick (extreme unction) closes earthly eyes and prepares the soul for its last passage.

People are born, they come of age, they marry or dedicate themselves completely to some life-purpose, and they die. The Sacraments provide the spiritual counterparts of these natural events of human life.

Meanwhile two Sacraments need to be repeated frequently. One of these is Reconciliation (confession). Being what we are, people cannot live without falling into error and straying from the right. These aberrations make necessary definite steps by which they may be restored to the human community and divine fellowship. The Church teaches that if one confesses one’s sin to God in the presence of one of God’s delegates, a priest, and truly repents of the sin committed and honestly resolves (whether or not this resolve proves effective) to avoid it in the future, one will be forgiven. God’s forgiveness depends on the sinner’s penitence and resolve being genuine, but the priest has no infallible means for determining whether they are or not. If the penitent deceives himself or herself and the priest, the absolution pronounced is inoperative.

Reconciliation (confession) is a Sacrament that needs to be repeated frequently to restore a person to the human community and divine fellowship.

The central Sacrament of the Catholic Church is the Mass, known also as the Holy Eucharist, Holy Communion, or the Lord’s Supper. The word Mass derives from the Latin missa, which is a form of the verb “to send.” The ancient liturgy contained two dismissals, one for people interested in Christianity but not yet baptized, which preceded the sacrament of the Eucharist, and a second for fully initiated Christians after it had been celebrated. Coming as it did between these two dismissals, the rite came first to be called missa and then, by transliteration, the Mass.

The central Sacrament of the Catholic Church is the Mass, known also as the Holy Eucharist, Holy Communion, or the Lord’s Supper.

The central feature of the Mass is the reenactment of Christ’s Last Supper in which, as he gave his disciples bread and wine, he said, “This is my blood that is shed for you.” It is false to the Catholic concept of this Sacrament to think of it as a commemoration through which priest and communicants elevate their spirits by symbolic remembrance of Christ’s example. The Mass provides an actual transfusion of spiritual energy from God to human souls. In a general way this holds for all the Sacraments, but for the Mass it holds uniquely. For the Catholic Church teaches that in the host and the chalice, the consecrated bread and wine, Christ’s human body and blood are actually present. They consider his words, “This is my body…. This is my blood,” explicit on this point. When a priest utters these words of consecration, therefore, the change that they effect in the elements is not one of significance only. The elements may not appear different afterward; analysis would register no chemical change. In technical language this means that their “accidents” remain as they were, but their “substance” is transubstantiated. We might say the Eucharist conveys God’s grace as a boat conveys its passengers, whereas the other sacraments convey grace as a letter conveys meaning. For the letter to have meaning, intelligence is required in addition to the paper and ink marks; so too in Sacraments other than the Eucharist God’s power is necessary in addition to the instruments of the sacrament. But in the Mass spiritual nourishment is literally to be had from the elements themselves. It is exactly as important for the Christians’ spiritual life to feast upon them as it is for their bodily lives to partake of food. Opening your mouth for the Bread of Life, writes Saint Francis de Sales,

full of faith, hope and charity, receive Him, in whom, by whom, and for whom, you believe, hope and love…. Represent to yourself that as the bee, after gathering from the flowers the dew of heaven and the choicest juice of the earth, reduces them into honey and carries it into her hive, so the priest, having taken from the altar the Savior of the world, the true Son of God, who, as the dew, is descended from heaven, and the true Son of the Virgin, who, as a flower is sprung from the earth of our humanity, puts him as delicious food into your mouth and into your body.

The central feature of the Mass is the reenactment of Christ’s Last Supper in which, as he gave his disciples bread and wine, he said, “This is my blood that is shed for you.” It is not a commemoration through which priest and communicants elevate their spirits by symbolic remembrance of Christ’s example. The Mass provides an actual transfusion of spiritual energy from God to human souls. In the Mass spiritual nourishment is literally to be had from the elements themselves.

This personal presence of God in the elements of the Mass distinguishes it significantly from the other Sacraments, but it does not vitiate the common bond that unites them all. Each is a means by which God, through Christ’s mystical body, literally infuses into human souls the supernatural power that enables them so to live in this world that in the world to come they may have life everlasting.

All Sacraments infuse into human souls the supernatural power that enables them so to live in this world that in the world to come they may have life everlasting.

Catholics see Christ as having explicitly joined the sacramental agency of the Church to its teaching authority in his closing commission to his disciples. “Go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, to the close of the age” (Matthew 28:19–20).

Catholics see Christ as having explicitly joined the sacramental agency of the Church to its teaching authority in his closing commission to his disciples.

.