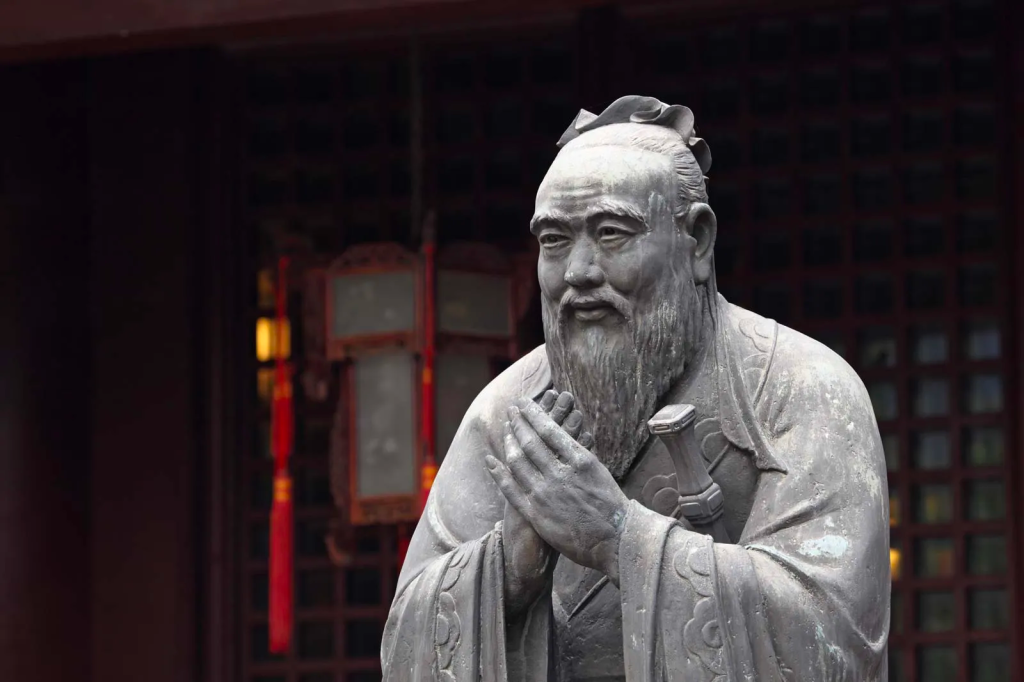

Reference: Confucianism

[NOTE: In color are Vinaire’s comments.]

The first individualists were probably wild mutants, lonely eccentrics who raised strange questions and resisted group identification not out of caprice but from the simple inability to feel themselves completely one with the gang.

For the clue to Confucius’ power and influence, we must see both his life and his teaching against the background of the problem he faced. This was the problem of social anarchy.

Confucius was faced with the problem of social anarchy.

Early China had been neither more nor less turbulent than other lands. The eighth to the third centuries B.C., however, witnessed a collapse of the Chou Dynasty’s ordering power. Rival baronies were left to their own devices, creating a precise parallel to conditions in Palestine in the period of the Judges: “In those days there was no king in Israel; every man did what was right in his own eyes.”

The Chou Dynasty had been collapsing during Confucius’ time. Rival baronies were left to their own devices, creating considerable instability.

The almost continuous warfare of the age began in the pattern of chivalry. The chariot was its weapon, courtesy its code, and acts of generosity were accorded high honor. Confronted with invasion, a baron would send in bravado a convoy of provisions to the invading army. Or to prove that his men were beyond fear and intimidation, he would send, as messengers to his invader, soldiers who would slit their throats in his presence. As in the Homeric age, warriors of opposing armies, recognizing each other, would exchange haughty compliments from their chariots, drink together, and even trade weapons before doing battle.

The almost continuous warfare of the age began in the pattern of chivalry.

By Confucius’ time, however, the interminable warfare had degenerated from chivalry toward the unrestrained horror of the Period of the Warring States. The horror reached its height in the century following Confucius’ death. Contests between charioteers gave way to cavalry, with its surprise attacks and sudden raids. Instead of nobly holding their prisoners for ransom, conquerors put them to death in mass executions. Whole populations unlucky enough to be captured were beheaded, including women, children, and the aged. We read of mass slaughters of 60,000, 80,000, and even 400,000. There are accounts of the conquered being thrown into boiling cauldrons and their relatives forced to drink the human soup.

By Confucius’ time, however, the interminable warfare had degenerated from chivalry toward the unrestrained horror of the Period of the Warring States.

In such an age the question that eclipsed all others was: How can we keep from destroying ourselves? Answers differed, but the question was always the same. With the invention and proliferation of weapons of ever-increasing destructiveness, it is a question that in the twentieth century has come to haunt the entire world.

In such an age the question that eclipsed all others was: How can we keep from destroying ourselves?

As the clue to the power of Confucianism lies in its answer to this problem of social cohesion, we need to see that problem in historical perspective. Confucius lived at a time when social cohesion had deteriorated to a critical point. The glue was no longer holding. What had held society together up to then?

As the clue to the power of Confucianism lies in its answer to this problem of social cohesion, we need to see that problem in historical perspective.

Before life reached the human level, the answer was obvious. The glue that holds the pack, the herd, the hive together is instinct. The cooperation it produces among ants and bees is legendary, but throughout the subhuman world generally it can be counted on to ensure reasonable cooperation. There is plenty of violence in nature, but on the whole it is between species, not within them. Within the species an inbuilt gregariousness, the “herd instinct,” keeps life stable.

There is plenty of violence in nature, but on the whole it is between species, not within them. Within the species an inbuilt gregariousness, the “herd instinct,” keeps life stable.

With the emergence of the human species, this automatic source of social cohesion disappears. Man being “the animal without instincts,” no inbuilt mechanism can be counted on to keep life intact. What is now to hold anarchy in check? In the infancy of the species the answer was spontaneous tradition, or as the anthropologists sometimes say, “the cake of custom.” Through generations of trial and error, certain ways of behaving prove to contribute to the tribe’s well-being. Councils do not sit down to decide what the tribe wants and what behavior patterns will secure those wants; patterns simply take shape over centuries, during which generations fumble their way toward satisfying mores and away from destructive ones. Once the patterns becomes established—societies that fail to evolve viable ones presumably read themselves out of existence, for none have remained for anthropologists to study—they are transmitted from generation to generation unthinkingly. As the Romans would say, they are passed on to the young cum lacte, “with the mother’s milk.”

Man being “the animal without instincts,” no inbuilt mechanism can be counted on to keep life intact. Through generations of trial and error, certain ways of behaving prove to contribute to the tribe’s well-being.

Modern life has moved so far from the tradition-bound life of tribal societies as to make it difficult for us to realize how completely it is possible for mores to be in control. There are not many areas in which custom continues to reach into our lives to dictate our behavior, but dress and attire remains one of them. Guidelines are weakening even here, but it is still pretty much the case that if a corporation executive were to forget his necktie, he would have trouble getting through the day. Indecent exposure would not be the problem; he would simply have transgressed convention—his profession’s assumed (but for the most part not explicitly stated) dress code. This would immediately target him as an outsider; he would be suspected of aberrant, if not subversive, proclivities. His associates would regard him out of the corners of their eyes as—well, different. And this is not a comfortable way to be seen, which is what gives custom its power. Someone has ventured that in a woman’s certitude that she is wearing precisely the right thing for the occasion, there is a peace that religion can neither give nor take away.

There are not many areas in which custom continues to reach into our lives to dictate our behavior, but dress and attire remains one of them.

If we generalize to all areas of life this power of tradition, which we now seldom feel outside matters of attire, we shall have a picture of the tradition-oriented life of tribal societies. Two things about this life are of particular interest here. The first is its phenomenal capacity to keep asocial acts in check. There are tribes among the Eskimos and the Australian aborigines that do not even have words for disobedience. The second impressive thing is the spontaneous, unthinking way socialization by this means proceeds. No laws are formulated with penalties attached; no plans for the moral education of children intentionally devised. Group expectations are so strong and uncompromising that the young internalize them without question or deliberation. The Greenlanders have no conscious program of education, nevertheless anthropologists report that their children are impressively obedient, good-natured, and ready to help. American Indians are still living who remember a time when in their regions’ social controls were entirely internal. “There were no laws then. Everybody did what was right.”

Group expectations are so strong and uncompromising that the young internalize them without question or deliberation.

In early China, custom and tradition probably likewise provided sufficient cohesion to keep the community intact. Vivid evidence of its power has come down to us. There is, for example, the recorded case of a noble lady who was burned to death in a palace fire because she refused to violate convention and leave the house without a chaperon. The historian—a contemporary of Confucius—who reported the incident glosses it in a way that shows that convention had lost some of its force in his thinking but was still very much intact. He suggests that if the lady had been unmarried, her conduct would have been beyond question. But as she was not only a married woman but an elderly one at that, it might not have been “altogether unfitting under the circumstances” for her to have left the burning mansion unaccompanied.

In early China, custom and tradition probably likewise provided sufficient cohesion to keep the community intact.

The historian’s sensitivity to the past is stronger than most; not everyone in Confucius’ day gave even as much ear to tradition as did the reporter just cited. China had reached a new point in its social evolution, a point marked by the emergence of large numbers of individuals in the full sense of that word. Self-conscious rather than group-conscious, these individuals had ceased to think of themselves primarily in the first person plural and were thinking in the first person singular. Reason was replacing social conventions, and self-interest outdistancing the expectations of the group. The fact that others were behaving in a given way or that their ancestors had done so from time immemorial could no longer be relied on as sufficient reason for individuals to follow suit. Proposals for action had now to face peoples’ question, “What’s in it for me?”

In Confucius’ day, reason was replacing social conventions, and self-interest outdistancing the expectations of the group.

The old mortar that had held society together was chipping and flaking. In working their way out of the “cake of custom,” individuals had cracked that cake beyond repair. The rupture did not occur overnight; in history nothing begins or ends on time’s knife-edge, least of all cultural change. The first individualists were probably wild mutants, lonely eccentrics who raised strange questions and resisted group identification not out of caprice but from the simple inability to feel themselves completely one with the gang. But individualism and self-consciousness are contagious. Once they appear, they spread like epidemic and wildfire. Unreflective solidarity is a thing of the past.

The first individualists were probably wild mutants, lonely eccentrics who raised strange questions and resisted group identification not out of caprice but from the simple inability to feel themselves completely one with the gang.

.