Reference: Hinduism

Note: The original Text is provided below.

Previous / Next

The universe is like the Kalpataru tree. It grants all wishes, but together with consequences. It wises the soul up as it passes through it.

.

Summary

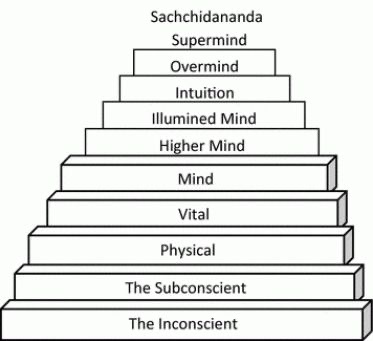

God in Hinduism appears to be total consciousness. Compared to God the human beings are limited in their consciousness as their attention is fixated in many ways.

Individual souls, or jivas, begin as the souls of the simplest forms of life, but they do not vanish with the death of their original bodies. They pass through a sequence of bodies. This process is known as reincarnation or transmigration of the soul. On the subhuman level the passage through a series of increasingly complex bodies is automatic until at last a human one is attained. With the soul’s graduation into a human body, this automatic, escalator-like mode of ascent comes to an end and self-consciousness begins.

With self-consciousness come freedom, responsibility, effort, and the law of karma. The law of karma is the moral law of cause and effect that brooks no exceptions. The present condition of each interior life is an exact product of what it has wanted and done in the past. Equally, its present thoughts and decisions are determining its future experiences. Each individual is wholly responsible for his or her present condition. The idea of a moral universe closes the door on chance or accident.

The law of karma does not mean fatalism. The consequences of one’s past decisions may create a certain condition, but one is free to decide how to handle that condition. This means that the career of a soul as it threads its course through innumerable human bodies is guided by its choices, which are controlled by what the soul wants and wills at each stage of the journey. Eventually, however, this entire program of personal ambition is seen for what it is: a game. The soul discovers that it is going round and round. The only good that can satisfy is one that is infinite and eternal.

The soul may fumble and zigzag its way toward what it really needs. In the long run, there is a gradual relaxation of attachment to physical objects and stimuli, accompanied by a progressive release from self-interest. Underlying its whirlpool of transient feelings, emotions, and delusions is the self-luminous, abiding point of Atman, the God within. Atman is the sole ground of human existence and awareness. Ultimately, the soul realizes that the universe is like the Kalpataru tree. It grants all wishes, but together with consequences. It wises the soul up as it passes through it.

.

Comments

The soul journeys through the universe to ultimately become fully conscious of the nature of the universe. With this comes the realization as to who or what it is.

.

Original Text

With God in pivotal position in the Hindu scheme, we can return to human beings to draw together systematically the Hindu concept of their nature and destiny.

Individual souls, or jivas, enter the world mysteriously; by God’s power we may be sure, but how or for what reason we are unable fully to explain. Like bubbles that form on the bottom of a boiling teakettle, they make their way through the water (universe) until they break free into the limitless atmosphere of illumination (liberation). They begin as the souls of the simplest forms of life, but they do not vanish with the death of their original bodies. In the Hindu view spirit no more depends on the body it inhabits than body depends on the clothes it wears or the house it lives in. When we outgrow a suit or find our house too cramped, we exchange these for roomier ones that offer our bodies freer play. Souls do the same.

Worn-out garments

Are shed by the body:

Worn-out bodies

Are shed by the dweller. (Bhagavad-Gita, II:22)

This process by which an individual jiva passes through a sequence of bodies is known as reincarnation or transmigration of the soul—in Sanskrit samsara, a word that signifies endless passage through cycles of life, death, and rebirth. On the subhuman level the passage is through a series of increasingly complex bodies until at last a human one is attained. Up to this point the soul’s growth is virtually automatic. It is as if the soul were growing as steadily and normally as a plant and receiving at each successive embodiment a body that, being more complex, provides the needed largess for its new capabilities.

With the soul’s graduation into a human body, this automatic, escalator-like mode of ascent comes to an end. Its entry into this exalted habitation is evidence that the soul has reached self-consciousness, and with this estate come freedom, responsibility, and effort.

The mechanism that ties these new acquisitions together is the law of karma. The literal meaning of karma (as we encountered it in karma yoga) is work, but as a doctrine it means, roughly, the moral law of cause and effect. Science has alerted the West to the importance of causal relationships in the physical world. Every physical event, we are inclined to believe, has its cause, and every cause will have its determinate effects. India extends this concept of causation to include moral and spiritual life as well. To some extent the West has as well. “As a man sows, so shall he reap”; or again, “Sow a thought and reap an act, sow an act and reap a habit, sow a habit and reap a character; sow a character and reap a destiny”—these are ways the West has put the point. The difference is that India tightens up and extends its concept of moral law to see it as absolute; it brooks no exceptions. The present condition of each interior life—how happy it is, how confused or serene, how much it sees—is an exact product of what it has wanted and done in the past. Equally, its present thoughts and decisions are determining its future experiences. Each act that is directed upon the world has its equal and opposite reaction on oneself. Each thought and deed delivers an unseen chisel blow that sculpts one’s destiny.

This idea of karma and the completely moral universe it implies carries two important psychological corollaries. First, it commits the Hindu who understands it to complete personal responsibility. Each individual is wholly responsible for his or her present condition and will have exactly the future he or she is now creating. Most people are not willing to admit this. They prefer, as the psychologists say, to project—to locate the source of their difficulties outside themselves. They want excuses, someone to blame so that they may be exonerated. This, say the Hindus, is immature. Everybody gets exactly what is deserved—we have made our beds and must lie in them. Conversely, the idea of a moral universe closes the door on chance or accident. Most people have little idea how much they secretly bank on luck—hard luck to justify past failures, good luck to bring future successes. How many people drift through life simply waiting for the breaks, for that moment when a lucky lottery number brings riches and a dizzying spell of fame. If you approach life this way, says Hinduism, you misjudge your position pathetically. Breaks have nothing to do with protracted levels of happiness, nor do they happen by chance. We live in a world in which there is no chance or accident. Those words are simply covers for ignorance.

Because karma implies a lawful world, it has often been interpreted as fatalism. However often Hindus may have succumbed to this interpretation, it is untrue to the doctrine itself. Karma decrees that every decision must have its determinate consequences, but the decisions themselves are, in the last analysis, freely arrived at. To approach the matter from the other direction, the consequences of one’s past decisions condition one’s present lot, as a card player finds himself dealt a particular hand while remaining free to play that hand in a variety of ways. This means that the career of a soul as it threads its course through innumerable human bodies is guided by its choices, which are controlled by what the soul wants and wills at each stage of the journey.

What its wants are, and the order in which they appear, can be summarized quickly here, for previous sections have considered them at length. When it first enters a human body, a jiva (soul) wants nothing more than to taste widely of the sense delights its new physical equipment makes possible. With repetition, however, even the most ecstatic of these falls prey to habituation and grows monotonous, whereupon the jiva turns to social conquests to escape boredom. These conquests—the various modes of wealth, fame, and power—can hold the individual’s interest for a considerable time. The stakes are high and their attainment richly gratifying. Eventually, however, this entire program of personal ambition is seen for what it is: a game—a fabulous, exciting, history-making game, but a game all the same.

As long as it holds one’s interest, it satisfies. But when novelty wears off, when a winner has acknowledged with the same bow and pretty little speech the accolades that have come so many times before, he or she begins to yearn for something new and more deeply satisfying. Duty, the total dedication of one’s life to one’s community, can fill the need for a while, but the ironies and anomalies of history make this object too a revolving door. Lean on it and it gives, but in time one discovers that it is going round and round. After social dedication the only good that can satisfy is one that is infinite and eternal, whose realization can turn all experience, even the experience of time and apparent defeat, into splendor, as storm clouds drifting through a valley look different viewed from a peak that is bathed in sunshine. The bubble is approaching the water’s surface and is demanding final release.

The soul’s progress through these ascending strata of human wants does not take the form of a straight line with an acute upward angle. It fumbles and zigzags its way toward what it really needs. In the long run, however, the trend of attachments will be upward—everyone finally gets the point. By “upward” here is meant a gradual relaxation of attachment to physical objects and stimuli, accompanied by a progressive release from self-interest. We can almost visualize the action of karma as it delivers the consequences of what the soul reaches out for. It is as if each desire that aims at the ego’s gratification adds a grain of concrete to the wall that surrounds the individual self and insulates it from the infinite sea of being that surrounds it; while, conversely, each compassionate or disinterested act dislodges a grain from the confining dike. Detachment cannot be overtly assessed, however; it has no public index. The fact that someone withdraws to a monastery is no proof of triumph over self and craving, for these may continue to abound in the imaginations of the heart. Conversely, an executive may be heavily involved in worldly responsibilities; but if he or she manages them detachedly—living in the world as a mudfish lives in the mud, without the mud’s sticking to it—the world becomes a ladder to ascend.

Never during its pilgrimage is the human spirit completely adrift and alone. From start to finish its nucleus is the Atman, the God within, exerting pressure to “out” like a jack-in-the-box. Underlying its whirlpool of transient feelings, emotions, and delusions is the self-luminous, abiding point of the transpersonal God. Though it is buried too deep in the soul to be normally noticed, it is the sole ground of human existence and awareness. As the sun lights the world even when cloud-covered, “the Immutable is never seen but is the Witness; It is never heard but is the Hearer; it is never thought, but is the Thinker; is never known, but is the Knower. There is no other witness but This, no other knower but This.” But God is not only the empowering agent in the soul’s every action. In the end it is God’s radiating warmth that melts the soul’s icecap, turning it into a pure capacity for God.

What happens then? Some say the individual soul passes into complete identification with God and loses every trace of its former separateness. Others, wishing to taste sugar, not be sugar, cherish the hope that some slight differentiation between the soul and God will still remain—a thin line upon the ocean that provides nevertheless a remnant of personal identity that some consider indispensable for the beatific vision.

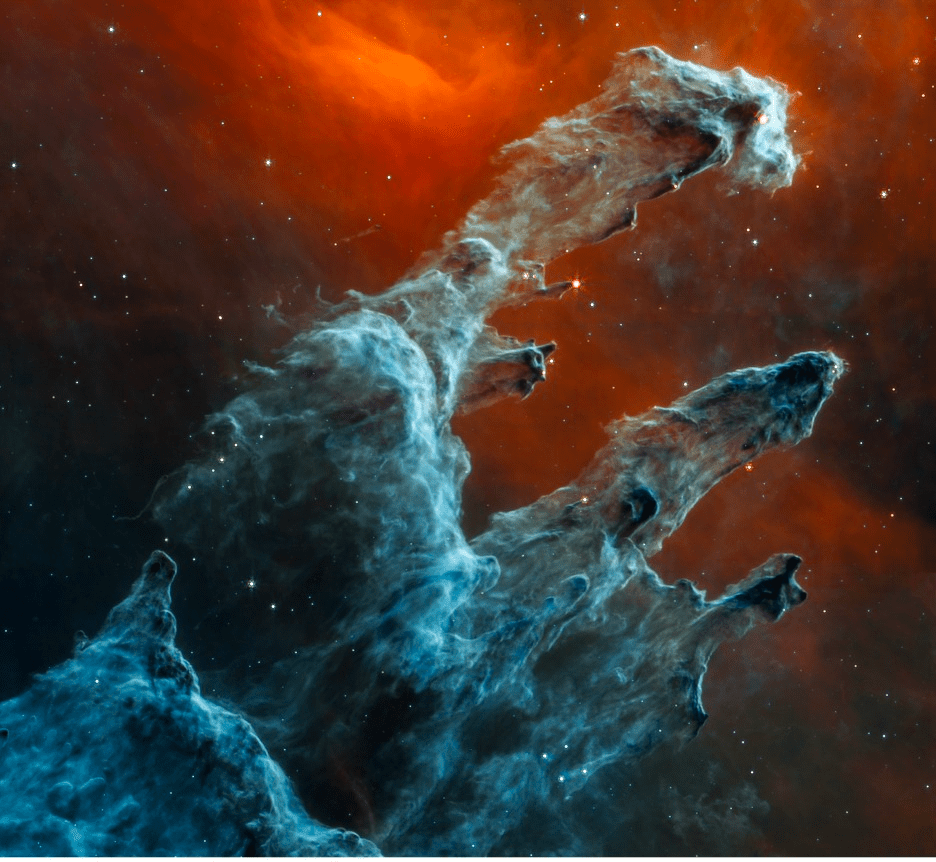

Christopher Isherwood has written a story based on an Indian fable that summarizes the soul’s coming of age in the universe. An old man seated on a lawn with a group of children around him tells them of the magic Kalpataru tree that fulfills all wishes. “If you speak to it and tell it a wish; or if you lie down under it and think, or even dream, a wish, then that wish will be granted.” The old man proceeds to tell them that he once obtained such a tree and planted it in his garden. “In fact,” he tells them, “that is a Kalpataru over there”.

With that the children rush to the tree and begin to shower it with requests. Most of these turn out to be unwise, ending in either indigestion or tears. But the Kalpataru grants them indiscriminately. It has no interest in giving advice.

Years pass, and the Kalpataru is forgotten. The children have now grown into men and women and are trying to fulfill new wishes that they have found. At first they want their wishes to be fulfilled instantly, but later they search for wishes that can be fulfilled only with ever-increasing difficulty.

The point of the story is that the universe is one gigantic Wishing Tree, with branches that reach into every heart. The cosmic process decrees that sometime or other, in this life or another, each of these wishes will be granted—together, of course, with consequences. There was one child from the original group, however, so the story concludes, who did not spend his years skipping from desire to desire, from one gratification to another. For from the first he had understood the real nature of the Wishing Tree. “For him, the Kalpataru was not the pretty magic tree of his uncle’s story—it did not exist to grant the foolish wishes of children—it was unspeakably terrible and grand. It was his father and his mother. Its roots held the world together, and its branches reached beyond the stars. Before the beginning it had been—and would be, always.”

.