Reference: SC: Psychology

NOTE: Text in color contains Vinaire’s comments.

Divergent Paths and Shared Insights

.

Epistemological Frameworks

The first millennium of the Christian Era witnessed fundamentally different trajectories in Eastern and Western approaches to mental illness, yet certain themes emerged across cultures that suggest universal aspects of human psychological understanding.

Western approaches oscillated between naturalistic and supernatural explanations. The Greco-Roman medical tradition established by Hippocrates, systematized by Celsus, and elaborated by Galen provided a coherent naturalistic framework based on humoral imbalance and brain pathology. However, the rise of Christianity introduced competing supernatural explanations centered on sin, demonic possession, and divine punishment. Byzantine medicine preserved the Greco-Roman naturalistic tradition while existing within a Christian cultural matrix, creating a complex synthesis. The Desert Fathers developed a third approach—neither purely naturalistic nor crudely supernatural—that understood mental afflictions as spiritual-psychological states requiring disciplined cognitive and contemplative interventions.

Eastern approaches generally maintained more consistent naturalistic frameworks while integrating spiritual dimensions without contradiction. Indian Ayurvedic medicine understood mental illness through the lens of dosha imbalance while accommodating supernatural etiologies (the agantuja category of unmada) without allowing them to dominate the medical framework. Buddhist psychology grounded mental suffering in the universal mechanisms of attachment, aversion, and ignorance, locating the problem and the solution entirely within the structure of consciousness itself. Chinese medicine integrated emotional and physiological dimensions seamlessly, viewing mental disorders as disruptions in the flow of qi and imbalances among organ systems. Islamic medicine synthesized Greek, Persian, and Indian knowledge while firmly rejecting supernatural explanations, insisting that mental illness was a medical condition requiring rational treatment.

Western approaches to mental illness oscillated between naturalistic and supernatural explanations; whereas, Eastern approaches generally maintained more consistent naturalistic frameworks while integrating spiritual dimensions without contradiction.

.

Therapeutic Modalities

Despite diverse theoretical frameworks, practical therapeutic interventions showed remarkable convergence across cultures. Pharmacological treatments were universal: Western physicians prescribed various herbal compounds, purgatives, and dietary modifications; Ayurvedic medicine employed extensive materia medica tailored to dosha imbalances; Chinese medicine developed complex herbal formulas; Islamic physicians like Alexander of Tralles and Al-Razi utilized hundreds of pharmaceutical preparations.

Psychotherapeutic interventions emerged independently across traditions. Roman physicians like Asclepiades advocated humane treatment including “light, music, and hydrotherapy”. Galen emphasized “counsel and education”. Ayurvedic texts prescribed treatments through “knowledge, specific knowledge, restraint, memory, and concentration”, using “exposure of the patient to mutually contradictory psychic factors” for emotional disturbances. Buddhist psychology developed systematic cognitive techniques for removing intrusive thoughts that closely parallel modern CBT. The Desert Fathers created contemplative practices for “guarding the heart” and managing the “demon of acedia”. Islamic physicians like Al-Razi pioneered psychotherapy, emphasizing positive therapeutic relationships and using sudden emotional reactions to catalyze healing.

Environmental and occupational therapies appeared across cultures. Greek and Roman physicians recommended travel, exercise, and pleasant environments. Byzantine hospitals provided comprehensive care. Islamic bimaristans employed “occupational therapy, aromatherapy, baths, and music therapy”. Chinese medicine emphasized appropriate environmental conditions for emotional balance. The convergence suggests these approaches addressed genuine therapeutic needs recognized across diverse cultural contexts.

Despite diverse theoretical frameworks, practical therapeutic interventions showed remarkable convergence across cultures. The convergence suggests these approaches addressed genuine therapeutic needs recognized across diverse cultural contexts.

.

The Role of Spirituality and Religion

The relationship between religious/spiritual frameworks and mental health treatment varied significantly. In the Christian West, increasing religious dominance often displaced medical frameworks, though this was neither universal nor uncontested. Byzantine physicians maintained professional medical approaches while practicing Christianity. Monastic psychology, rather than rejecting naturalistic understanding, developed sophisticated introspective techniques grounded in systematic observation of mental states.

In the East, spiritual and medical frameworks achieved greater integration. Ayurvedic medicine embedded treatment within a comprehensive philosophical worldview without the spiritual dimension overwhelming medical observation. Buddhism developed psychological systems that were simultaneously therapeutic practices and paths to enlightenment—the distinction between treating mental illness and achieving awakening was one of degree rather than kind. Chinese medicine integrated spiritual concepts like Shen with physiological observation seamlessly. Islamic medicine, while deeply embedded in Islamic civilization, insisted on the medical nature of mental illness and rational treatment, achieving a synthesis where faith informed ethics without dictating medical theory.

The relationship between religious/spiritual frameworks and mental health treatment varied significantly. In the Christian West, increasing religious dominance often displaced medical frameworks. In the East, spiritual and medical frameworks achieved greater integration.

.

Institutional Developments

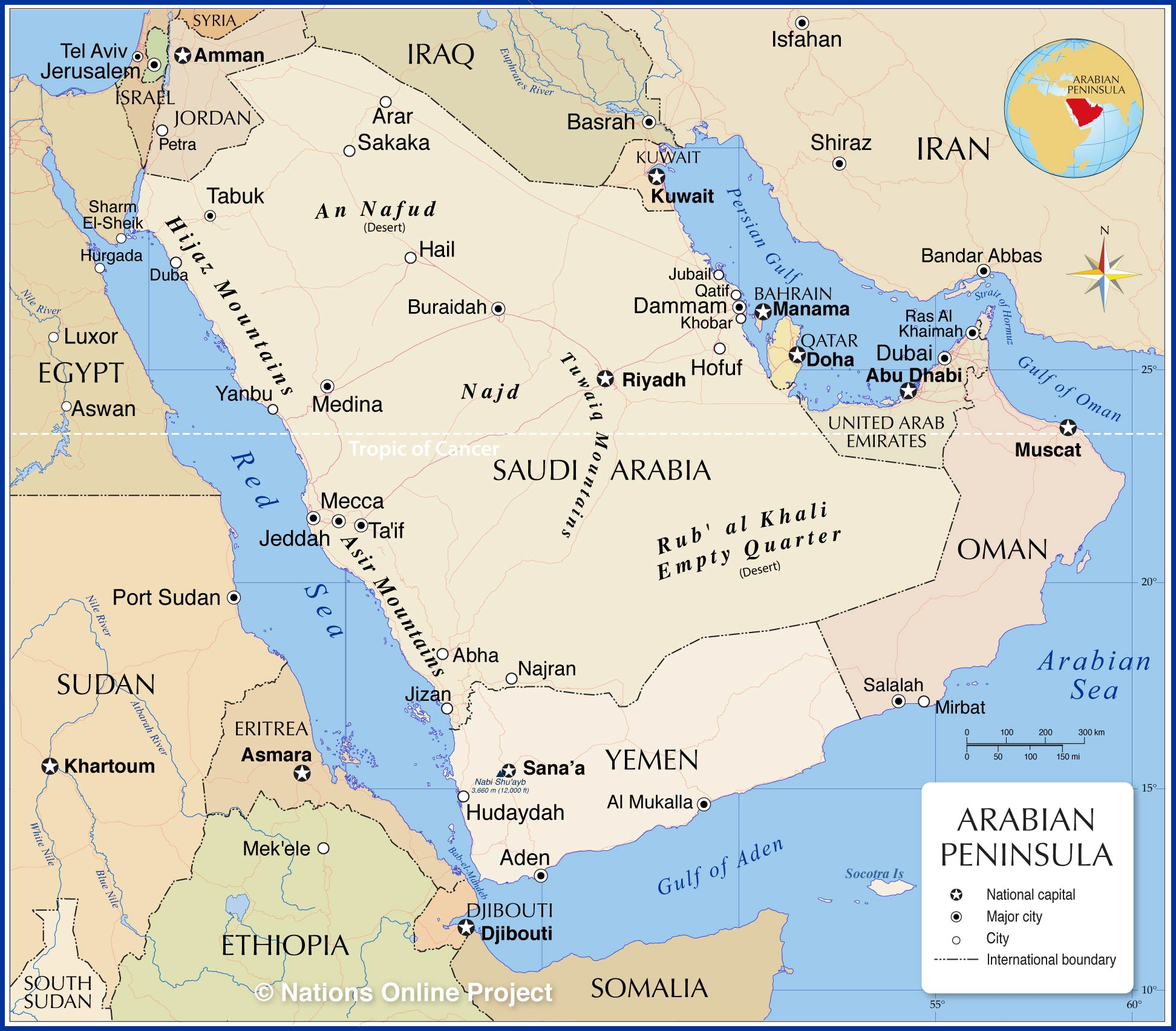

The development of specialized institutions for mental health care emerged most dramatically in the Islamic world with Al-Razi’s psychiatric ward and the bimaristan system. While Byzantine hospitals included medical care and Western monasteries provided refuge for the mentally distressed, these institutions did not develop the specialized, systematic approach to psychiatric treatment seen in Islamic medicine. The bimaristans represented “centers of healing, where monks utilized a combination of herbal remedies, dietary regulations, and spiritual rituals to address physical and mental health issues”, but with explicit medical organization and trained physician staff.

Chinese and Indian contexts developed different institutional patterns. While hospitals existed in ancient India and China, the available evidence from this period does not document specialized psychiatric facilities comparable to the Islamic bimaristans. However, monastic communities in both Buddhist and Hindu contexts provided structured environments for mental cultivation and healing, functioning as therapeutic communities even if not formally organized as medical institutions.

The development of specialized institutions for mental health care emerged most dramatically in the Islamic world. While other places provided refuge for the mentally distressed and medical care, these institutions did not develop the specialized, systematic approach to psychiatric treatment seen in Islamic medicine.

.