Reference: The Story of Philosophy

This paper presents Chapter XI Section 3.2 from the book THE STORY OF PHILOSOPHY by WILL DURANT. The contents are from the 1933 reprint of this book by TIME INCORPORATED by arrangement with Simon and Schuster, Inc.

The paragraphs of the original material (in black) are accompanied by brief comments (in color) based on the present understanding.

.

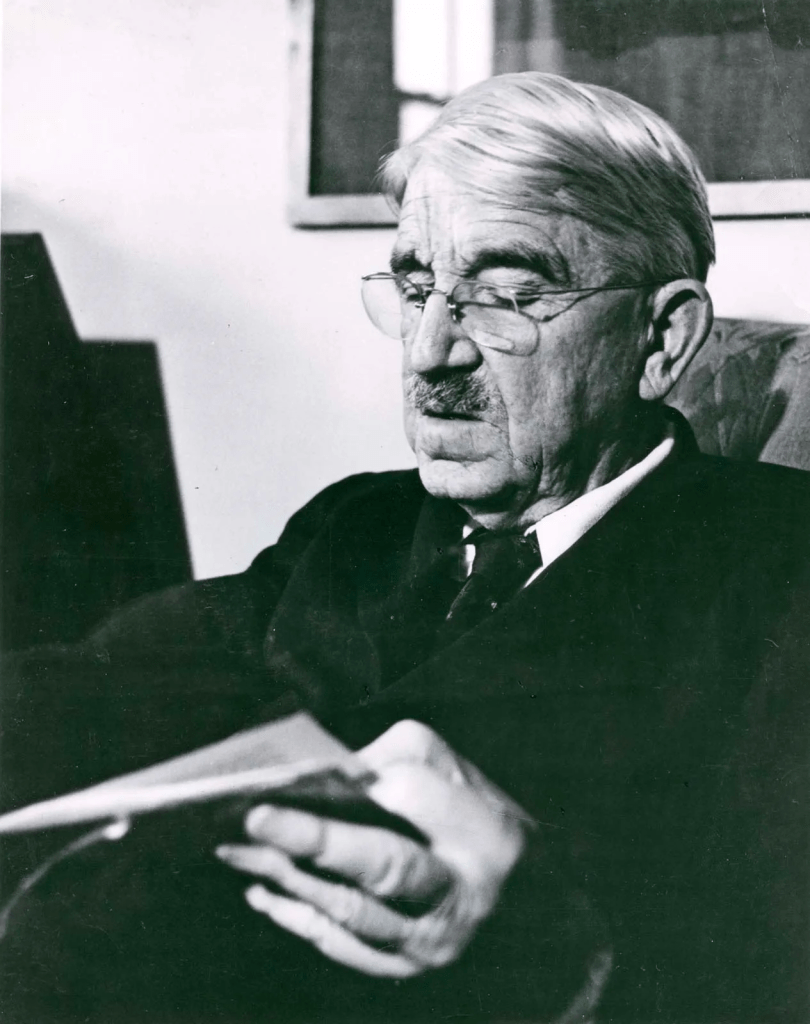

III. JOHN DEWEY

2. Instrumentalism

What distinguishes Dewey is the undisguised completeness with which he accepts the evolution theory. Mind as well as body is to him an organ evolved, in the struggle for existence, from lower forms. His starting-point in every field is Darwinian.

When Descartes said, “The nature of physical things IS much more easily conceived when they are beheld coming gradually into existence, than when they are only considered as produced at once in a finished and perfect state,” the modern world became self-conscious of the logic that was henceforth to control it, the logic of which Darwin’s Origin of Species, is the latest scientific achievement. … When Darwin said of species what Galileo had said of the earth, e pur si muove [and yet it moves], he emancipated, once for all, genetic and experimental ideas as an organon of asking questions and looking for explanations.

What distinguishes Dewey is the undisguised completeness with which he accepts the evolution theory. Mind as well as body is to him an organ evolved, in the struggle for existence, from lower forms. His starting-point in every field is Darwinian.

Things are to be explained, then, not by supernatural causation, but by their place and function in the environment. Dewey is frankly naturalistic; he protests that “to idealize and rationalize the universe at large is a confession of inability to master the courses of things that specifically concern us.” He distrusts, too, the Schopenhauerian Will and the Bergsonian élan; these may exist, but there is no need to worship them; for these world-forces are as often as not destructive of everything that man creates and reverences. Divinity is within us, not in these neutral cosmic powers. “Intelligence has descended from its lonely isolation at the remote edge of things, whence it operated as unmoved mover and ultimate good, to take its seat in the moving affairs of men.” We must be faithful to the earth.

Things are to be explained, then, not by supernatural causation, but by their place and function in the environment. We need to master the courses of things that specifically concern us. Divinity is within us, not in these neutral cosmic powers.

Like a good positivist, scion of the stock of Bacon and Hobbes and Spencer and Mill, Dewey rejects metaphysics as the echo and disguise of theology. The trouble with philosophy has always been that its problems were confused with those of religion. “As I read Plato, philosophy began with some sense of its essentially political basis and mission—a recognition that its problems were those of the organization of a just social order. But it soon got lost in dreams of another world.” In German philosophy the interest in religious problems deflected the course of philosophic development; in English philosophy the social interest outweighed the supernatural. For two centuries the war raged between an idealism that reflected authoritarian religion and feudal aristocracy, and a sensationalism that reflected the liberal faith of a progressive democracy.

The trouble with philosophy has always been that its problems were confused with those of religion. Philosophy began with the problem of the organization of a just social order. But it soon got lost in dreams of another world.

This war is not yet ended; and therefore we have not quite emerged from the Middle Ages. The modern era will begin only when the naturalist point of view shall be adopted in every field. This does not mean that mind is reduced to matter, but only that mind and life are to be understood not in theological but in biological terms, as an organ or an organism in an environment, acted upon and reacting, moulded and moulding. We must study not “states of consciousness” but modes of response. “The brain is primarily an organ of a certain kind of behavior, not of knowing the world.” Thought is an instrument of re-adaptation; it is an organ as much as limbs and teeth. Ideas are imagined contacts, experiments in adjustment. But this is no passive adjustment, no merely Spencerian adaptation. “Complete adaptation to environment means death. The essential point in all response is the desire to control the environment.” The problem of philosophy is not how we can come to know an external world, but how we can learn to control it and remake it, and for what goals. Philosophy is not the analysis of sensation and knowledge (for that is psychology), but the synthesis and coordination of knowledge and desire.

The problem of philosophy is not how we can come to know an external world, but how we can learn to control it and remake it, and for what goals. Philosophy is not the analysis of sensation and knowledge, but the synthesis and coordination of knowledge and desire.

To understand thought we must watch it arise in specific situations. Reasoning, we perceive, begins not with premises, but with difficulties; then it conceives an hypothesis which becomes the conclusion for which it seeks the premises; finally it puts the hypothesis to the test of observation or experiment. “The first distinguishing characteristic of thinking is facing the facts—inquiry, minute and extensive scrutinizing, observation.” There is small comfort for mysticism here.

The first distinguishing characteristic of thinking is facing the facts—inquiry, minute and extensive scrutinizing, observation.

And then again, thinking is social; it occurs not only in specific situations, but in a given cultural milieu. The individual is as much a product of society as society is a product of the individual; a vast network of customs, manners, conventions, language, and traditional ideas lies ready to pounce upon every new-born child, to mould it into the image of the people among whom it has appeared. So rapid and thorough is the operation of this social heredity that it is often mistaken for physical or biological heredity. Even Spencer believed that the Kantian categories, or habits and forms of thought, were native to tne individual, whereas in all probability they are merely the product of the social transmission of mental habits from adults to chlIdren. In general the role of instinct has been exaggerated, and that of early training under-rated; the most powerful instincts, such as sex and pugnacity, have been considerably modified and controlled by social training; and there is no reason why other instincts, like those of acquisition and mastery, should not be similarly modified by social influence and education. We must unlearn our ideas about an unchangeable human nature and an omnipotent environment. There is no knowable limit to change or growth; and perhaps there is nothing impossible but thinking makes it so.

The individual is as much a product of society as society is a product of the individual. So rapid and thorough is the operation of this social heredity that it is often mistaken for physical or biological heredity. We must unlearn our ideas about an unchangeable human nature and an omnipotent environment.

.