Reference: The Book of Physics

Note: The original text is provided below.

Previous / Next

Summary

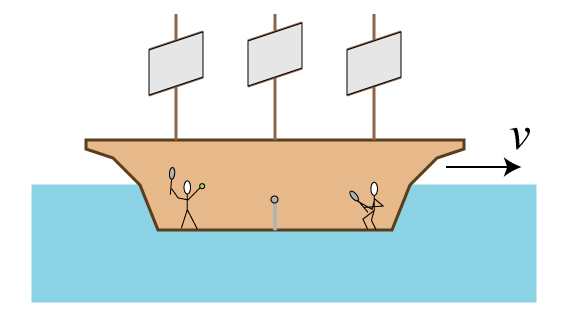

We are confronted by the fact that we do not know the absolute motion of bodies in space by comparing it to a body at complete rest. We only know their relative motions. Each body has its own frame of space within which perception occurs and measurements are made. The measurements are consistent within each frame of reference, but they do not have an absolute basis just like the motion of the body has no absolute basis.

We may accept all measurements to be relative. But then we do not have an absolute view of the universe. We run into mystery about cosmic phenomenon, such as, gravity.

.

Comments

The solution to the problem of relativity requires a universal invariant such as a body at complete rest. Einstein used the velocity of light to be invariant. But, this is not fully verified. The velocity of light appears as an invariant only because it is so large compared to the motion in material realm, and for no other reason. It does fully resolve the problem of gravity.

.

Original Text

Let us take a last glance back before we plunge into four dimensions. We have been confronted with something not contemplated in classical physics—a multiplicity of frames of space, each one as good as any other. And in place of a distance, magnetic force, acceleration, etc., which according to classical ideas must necessarily be definite and unique, we are confronted with different distances, etc., corresponding to the different frames, with no ground for making a choice between them. Our simple solution has been to give up the idea that one of these is right and that the others are spurious imitations, and to accept them en bloc; so that distance, magnetic force, acceleration, etc., are relative quantities, comparable with other relative quantities already known to us such as direction or velocity. In the main this leaves the structure of our physical knowledge unaltered; only we must give up certain expectations as to the behaviour of these quantities, and certain tacit assumptions which were based on the belief that they are absolute. In particular a law of Nature which seemed simple and appropriate for absolute quantities may be quite inapplicable to relative quantities and therefore require some tinkering. Whilst the structure of our physical knowledge is not much affected, the change in the underlying conceptions is radical. We have travelled far from the old standpoint which demanded mechanical models of everything in Nature, seeing that we do not now admit even a definite unique distance between two points. The relativity of the current scheme of physics invites us to search deeper and find the absolute scheme underlying it, so that we may see the world in a truer perspective.

.