Reference: Beginning Physics II

Chapter 18: ATOMIC, NUCLEAR AND SOLID-STATE PHYSICS

.

KEY WORD LIST

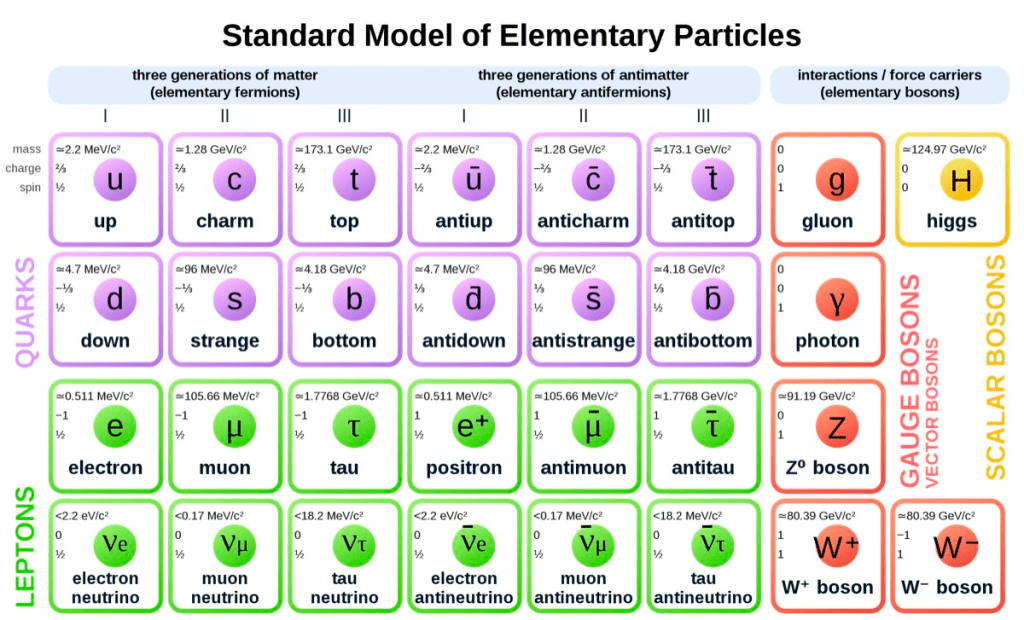

Atom, Bohr Atom, Energy Level Diagram, Quantized Energy Levels, Bohr’s Theory, Quantum Theory of Atom, Principal Quantum Number (n), Electron Shells, Second Quantum Number (l), Third Quantum Number (ml), Fourth Quantum Number (ms), Bohr Radius, Electron Probability Cloud, Pauli Exclusion Principle, Bremsstrahlung radiation, X-Ray Lines, Ground State, Excited State, Spontaneous Emission, Stimulated Emission, Laser, Binding Energy, Mass Defect, Maximum Binding Energy, Radioactivity, Half-Life, Dating, Conservation Laws, Natural Decay Processes, Neutrino, Positron, γ-Decay, Induced Reactions, Fission Reaction, Nuclear Energy, Chain Reaction, Cross-Section, Enrichment, Breeder Reactors, Moderator, Critical Reaction, Control Rods, Fusion Reactions, Elementary Particles, Baryons, Leptons, Anti-Particle, Photon, Virtual Photons, Electrodynamics, Muon, Strong Interaction, Weak Interaction, Tau Particle, Meson, Hadron, Quarks, Strangeness, Gluons, “Color” Charge, Chromodynamics, Standard Model, Solid-State Physics, Crystal, Energy “Band”, Energy Gap And Overlap, Energy Gap And Overlap, Conduction Band, Insulator, Semiconductor, Holes, N-Type Semiconductor, P-Type Semiconductor, Photodetectors.

(From KHTK) Atomic Structure, Electron Shells, Charge, Nuclear Shells, Fundamental Particles

.

GLOSSARY

For details on the following concepts, please consult Chapter 18.

ATOM

An atom is composed of a positively charged nucleus consisting of protons and neutrons and a surrounding shell of negatively charged electrons which have about 2000 times less mass than the protons and neutrons of the nuclei.

BOHR ATOM

Bohr assumed that a wave drawn around the circle representing the path of the electron is an integral multiple of the wavelength. Thus, he asserted that the angular momentum is quantized in multiples of h, and that the only possible allowed orbits for the electron were ones with such an angular momentum. Niels Bohr showed that if one makes certain ad hoc assumptions about quantization, like those suggested by Planck for the black-body radiation, he could indeed explain some detailed phenomena associated with atoms containing a single electron

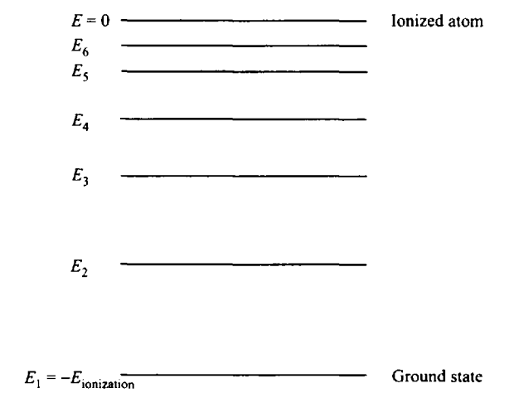

ENERGY LEVEL DIAGRAM

We usually picture the allowed states for the atom in an energy level diagram. Here, the energy is zero if the nucleus and the electrons are not bound to each other (Ionized atom). The ground state is the lowest allowed energy (E1) bound state, and it is negative. The atom can make a transition by moving from one allowed level to another.

QUANTIZED ENERGY LEVELS

The Bohr theory of the atom thus predicts the existence of quantized energy levels, each associated with a distinct label, n, which is called the quantum number of that level. In those levels the atom cannot radiate away any energy unless, after losing an amount of radiant energy, the atom finds itself in another allowed energy level. Thus, only specific frequencies of radiation (and correspondingly, only specific wavelengths) can be radiated by an atom. Some of these transitions are shown in the diagram below.

BOHR’S THEORY

The Bohr theory was successful in giving a rationale for the stability of atoms, and it correctly predicted the wavelengths of radiation from single electron atoms. The theory further showed that the radiation from atoms in general was determined by differences in energy levels of the atoms. However, his theory was unable to be generalized to atoms with more than one electron and was unable to explain why the energy levels of atoms should be quantized in the first place.

QUANTUM THEORY OF ATOM

In the quantum theory, the behavior of electrons is determined by the wavefunction solutions of Schrödinger’s equation, which yield the probability that a particle is at a given point in space at a given time. There are stationary solutions of this equation only for certain energies that can be found for bound states. These solutions require labels n, l, and m in three dimensions. It was experimentally determined from the details of the radiation emitted by these atoms, that a fourth label was required as well. These labels are called “quantum numbers” and the accepted notation for these quantum numbers in a one electron atom are n, 1, ml and ms. This fourth quantum number arises from a purely quantum mechanical concept, the intrinsic spin of the electron.

PRINCIPAL QUANTUM NUMBER (n)

The quantum number n is called the principal quantum number. It corresponds to the energy quantum number in Bohr’s theory. This number takes on integral values beginning with 1 with no upper bound. It is associated with the distance, r, between the nucleus and the electron; but the concept of a circulating electron in an orbit as prescribed by the Bohr theory, has no validity in quantum mechanics and angular momentum cannot be given a simple visual picture as in the Bohr theory.

ELECTRON SHELLS

In the case of multi electron atoms, all electrons with a common principal quantum number n are said to be in the same shell, approximating a single electron atom. All electrons with n = 1 are said to be in the K shell, and all have essentially the same energy. All electrons with the n = 2 are said to be in the L shell, with n = 3 they are in the M shell, with n = 4 in the N shell, etc

SECOND QUANTUM NUMBER (l)

The quantum number l is related to one of the angular coordinates. It is called the angular momentum quantum number, since it determines the magnitude of the orbital angular momentum of the electron about the nucleus. In multi electron atoms, the energy levels of an electron are dependent somewhat on 1 as well. For a given n, the allowed values of l are restricted to integers in the range from zero to (n – 1). All electrons with the same quantum number 1 have the same angular momentum.

Any electron with 1 = 0 is called an s electron and has no angular momentum. When 1 = 1, the electron has certain angular momentum and is called a p electron. When 1 = 2, the electron has a different value of angular momentum and is called a d electron. An electron with 1 = 3 is called an f electron, with 1 = 4 is called a g electron, etc.

THIRD QUANTUM NUMBER (ml)

The third quantum number ml is related to the second angular coordinate. It indicates the allowed directions for the angular momentum. This is called space quantization. For a given l the values of ml are restricted to integer values ranging from -l to +l. If 1 = 1, there are three possible values for ml: -1, 0, and + 1. This quantum number is often called the magnetic quantum number because the energy of an electron depends on ml in the presence of a magnetic field. The magnetic quantum number has only a very small effect on the energy of the quantum state, except when a magnetic field is existent. It is again important to reiterate that although angular momentum remains an important physical quantity in quantum mechanics, one cannot identify this quantity with the concept of a circulating electron! NOTE: See KHTK explanation below.

FOURTH QUANTUM NUMBER (ms)

We need an additional quantum number ms to get agreement between the theory and experiment. This additional quantum number does not arise from the motion of an electron in three dimensions, but rather arises from the intrinsic properties of the electron itself. If one assumes that the electron has an intrinsic spin (an internal spin about its own axis) which is quantized, then the atom has additional angular momentum due to the intrinsic spin. This assumption was an ad hoc assumption until quantum mechanics was made to conform to the theory of relativity and the Schrödinger equation was replaced by the Dirac equation. The relativistic equation predicted the correct value for the electron spin. This spin angular momentum is intrinsic to the electron just as its charge and its mass are. These intrinsic values cannot be increased or decreased.

As in the case of the orbital angular momentum, the spin angular momentum is also quantized in space, with its component restricted to two possible states. We assign two possible spins of ±1/2 to quantum number ms. We now must designate each energy level by four quantum numbers, n, 1, ml and ms. Because the electron is charged, the spinning electron produces a magnetic field which in turn impacts slightly on the energy levels of the electrons. With the addition of this spin, the theory agrees with experiment to a remarkable degree.

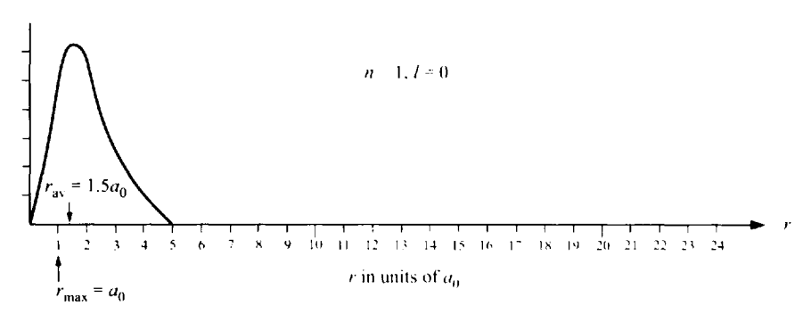

BOHR RADIUS

Bohr radius a0 = 5.29 x 10-l1 m, which is the radius of the lowest level orbit in the Bohr atom.

ELECTRON PROBABILITY CLOUD

We see that the electron cannot be located at any specific position in space, but rather there is an “electron probability cloud” in which the electron is concentrated. For n = 1, the maximum probability location for the electron is r = a0, while the average position of the electron is 1.5a0. The total probability of finding the electron at any radial distance is the area under the curve between r = 0 and r = ∞, and must equal 1 since the electron is definitely somewhere in this range.

PAULI EXCLUSION PRINCIPLE

This principle states that no more than one electron in an atom can have the same quantum numbers n, 1, ml and ms. We now know that this principle applies to any particle that has a spin of 1/2 (or 3/2, 5/2, etc.). In that case, only one electron can have the quantum numbers for the lowest energy level. The next electron will have to go into the next level, and subsequent electrons into ever higher levels.

BREMSSTRAHLUNG RADIATION

X-rays can be produced by taking energetic electrons and letting them strike a metal plate. The energy from a decelerating electron is converted directly to a photon. This is called Bremsstrahlung or braking radiation.

X-RAY LINES

X-ray lines are produced when the incident electron loses energy by a “collision” to one of the bound electrons in the material, resulting in the removal of that electron from the atom. If that removed electron is one of the inner electrons, then one of the outer electrons could transfer to this state. By dropping into the inner state, the electron loses energy, and that energy is radiated away by a photon with a wavelength corresponding to the difference in energy between the two states. These wavelengths are often in the X-ray region, especially for materials with many electrons. These characteristic wavelengths then appear in the X-ray spectrum in addition to the continuous spectrum of the Bremsstrahlung radiation.

GROUND STATE

The electrons in all the atoms would tend to be found in the “ground state”, in which the electrons fill the various levels from the bottom up, and thus has the lowest overall energy.

EXCITED STATE

If the electrons were somehow removed to a higher state, we say that the atom is in an “excited state,” and have a higher overall energy.

SPONTANEOUS EMISSION

In spontaneous emission, an excited state electron rapidly transitions downward emitting a photon of a definite frequency f.

STIMULATED EMISSION

When the atom can stay in the excited state for a relatively long time, and a photon at that definite frequency f, passes by, it can stimulate the electron to make the transition back to the ground state, by emitting a second photon at frequency f, that is in phase with the first photon. Such a process is called “stimulated emission”. The new photon also travels in the same direction as the initial photon.

LASER

When there are many atoms in the excited metastable state then each of the photons can stimulate other emissions which then stimulate even more emissions causing a cascade of photons at the same frequency. This radiation would be especially intense since the radiation from all the independent atoms are in phase with each other. This is the basic concept needed for understanding the operation of the laser.

BINDING ENERGY

Binding energy is the energy required to remove a nucleon from the nucleus. The energy required to separate all the nucleons from each other is the total binding energy (B.E.) of the nucleus. For a nucleus with A nucleons the average energy needed to remove one nucleon is (B.E.)/A, or the binding energy per nucleon. When one separates all the nucleons, one must supply this amount of energy per nucleon. The total binding energy, B.E., is also the amount of energy released when one forms the nucleus from individual nucleons.

MASS DEFECT

The binding energy released when one forms the nucleus from individual nucleons is equivalent to the mass lost. The nucleus will have less mass than the sum of the masses of its constituents. This “lost” mass is called the “mass defect”, and must be equal to the (B.E.)/c2. If we measure the mass of the nucleus, we can calculate the mass defect by comparing this mass to the sum of the masses of its constituents. This will then give us the binding energy of the nucleus.

MAXIMUM BINDING ENERGY

We note that a maximum (B.E.)/A of 8.77 MeV/nucleon occurs for Fe57. This nucleus has nucleons which are more tightly bound than in any other nucleus. If the nucleons in other nuclei would be able to rearrange themselves into Fe57, they would each release more energy until their new binding energy increases to 8.77 MeV/nucleon. This can occur if the light elements (A < 57) fuse together to form nuclei with larger A. One can also release energy by converting very heavy nuclei (such as uranium) into lighter nuclei which have a larger (B.E.)/A, thus releasing energy.

RADIOACTIVITY

Many nuclei, including those occurring naturally, are unstable, and they decay to another nucleus in a characteristic manner. Radioactivity is the emission of ionizing radiation or particles caused by the spontaneous disintegration of atomic nuclei. Highly radioactive means short half-life, weakly radioactive means long half-life.

HALF-LIFE

Each nuclear decay is characterized by a “half-life”, which is the average time that it takes for half of the nuclei to decay. Although one cannot predict which individual atom will have its nucleus decay at any time, only half the original nuclei remain after “half-life.”

DATING

One of the applications of naturally occurring radioactivity is in dating of geological or archeological samples. If one assumes that one knows the initial composition of a material in terms of the nuclei present, then, if some of the nuclei are radioactive, we can determine the age of the sample by measuring the composition at the present time.

This technique would allow us to date organic materials on the basis of the following assumptions: (1) The ratio of C12/C14 in the atmosphere has remained essentially stable over geologic time; (2) As an organic substance grows and absorbs carbon, the ratio absorbed is the same as the ratio in the sea of air above; (3) Once the organic material (e.g. a tree) dies there is no more carbon absorbed or emitted chemically, so that the only change in composition comes from the radioactive decay of the carbon 14. We can usually compensate for uncertainties in these assumptions, and in many cases, we can check the accuracy of age determinations by using additional radioactive decays of other isotopes. This has become a standard technique, although it requires careful measurements as well as thorough analysis to be sure that it is legitimately applied in each case.

CONSERVATION LAWS

From mechanics, we have the laws of conservation of energy, of linear momentum and of angular momentum. From electricity, we have the law of conservation of charge. All of these conservation laws must be satisfied in any decay that occurs in nature. In addition, we find in the naturally occurring decays that the total number of protons and neutrons (nucleons) must be the same before and after a decay.

NATURAL DECAY PROCESSES

There are three naturally occurring decays, which are called α, β and γ. In α -decay the particle emitted from a larger nucleus is the nucleus of a helium atom, in β-decay the particle emitted is an electron and in γ-decay the particle emitted is a photon. A particle will decay by itself only if the decay products have less rest mass than the original particle. The excess mass of the original particle is given as kinetic energy to the decay products.

NEUTRINO

Neutrino is a neutral subatomic particle with a mass close to zero and half-integral spin, rarely reacting with normal matter.

POSITRON

The positron or antielectron is the particle with an electric charge of +1e, a spin of 1/2, and the same mass as an electron. It is the antiparticle of the electron. When a positron collides with an electron, annihilation occurs.

γ-DECAY

Inγ-decay the effect of the emission of a y-ray is merely to carry away energy from the nucleus. We view this in the same manner as for atomic physics where a photon carries away energy as the electrons make transitions between different levels. Similarly, the nucleus has energy levels, and a photon is emitted when the nucleus makes a transition to a lower level.

INDUCED REACTIONS

In addition to the naturally occurring nuclear transformations via radioactivity, it is possible to induce nuclear transformations by bombarding the nucleus with another particle or nucleus. For instance, one can strike the nucleus with a proton, or a neutron, or an α -particle, or a γ -ray, etc. The result of such a collision could be a new nucleus plus the emission of a different particle or particles. In all such collisions, called nuclear reactions, the outcomes are restricted by all the conservation laws.

FISSION REACTION

If a uranium nucleus would “fission”, i.e. break apart into two smaller nuclei, then each nucleon on average would gain binding energy and this additional binding energy would be released in the form of kinetic energy given to the fission products. To help the uranium nucleus to fission, we can send in additional energy via a photon (photofission) or a neutron. Then the nucleus has enough energy to surmount the barrier and it will immediately break apart. Often, the products of fission include, in addition to massive nuclei, other more elemental particles such as neutrons.

NUCLEAR ENERGY

The energy released in a nuclear reaction is huge compared to the energy released in a chemical reaction of two atoms or two molecules, such as the explosion of TNT. In chemical reactions the energy released per molecular interaction is typically a few eV, which is 108 times smaller than the above fission reaction. This is why nuclear energy is much more potent than chemical energy.

CHAIN REACTION

We must arrange to have many nuclei fission to produce a large total amount of energy. This is made possible by using the extra neutrons that are released in each fission to initiate a new fission. The process is known as a “chain reaction”. If the chain is not controlled it could produce a large, nearly instantaneous release of energy as in a bomb. If it is controlled, the energy release can be gradual, as in a reactor.

CROSS-SECTION

The cross-section is the likelihood of fission occurring in a material. Only U235 (and a new nucleus, produced in reactions, plutonium, Pu239) has a sufficiently large cross-section for use in a reactor.

ENRICHMENT

Natural uranium contains mainly U238 (99.3%), with only 0.7% of U235. The cross-section of U238 is too small to use as a practical material. It is very difficult to separate U235 from U238 since both isotopes have the same chemical properties and they differ only slightly in mass. When one has “enriched” the uranium so that it contains about 3% of U235, one can use this mixture as the fuel for a reactor.

BREEDER REACTORS

One can build a reactor that produces more fuel (in the form of Pu239) than it consumes (in the form of U235). These reactors are called “breeder” reactors. The plutonium produced in these reactors can be chemically separated from the uranium and used as fuel for a fission reactor.

MODERATOR

The fission reaction that is induced by the incoming neutron produces extra neutrons, with a large amount of kinetic energy, which we want to use to induce further fissions in a chain reaction. However, only slow neutrons are efficient in inducing fission, so we first must slow down the neutrons. This is done by a “moderator”, which is a material with which the neutrons collide, and to which they transfer their energy. Energy transfer is most efficient if an energetic object collides with another body of roughly the same mass. The closest material in mass to neutron would be hydrogen (a proton), which is plentiful in water. However, water tends to absorb the neutron and form a deuteron (1H2), which removes the neutron from play instead of slowing it down, thus inhibiting the chain reaction tremendously. Therefore, “heavy” water, already made from deuterium is a much better alternative moderator.

CRITICAL REACTION

If the excess neutrons that are produced in a fission induce, on average, less than one new fission, then the reactor is “sub-critical” and will not produce a chain reaction. If more than one fission is induced, on average, then the reaction will increase rapidly in number, possibly leading to an explosion. If the average number of fissions induced by the extra neutrons is just one, the reactor is critical, and a chain reaction will be sustained.

CONTROL RODS

The number of induced fissions produced is controlled using “control rods” made of material that absorbs neutrons. These are automatically adjusted to keep the energy production at the intended level. Another control mechanism that prevents a properly constructed reactor from getting out of control is the fact that as the reactor core overheats, the moderator will boil away, and this will automatically reduce the number of slow neutrons and hence the fission reaction.

FUSION REACTIONS

The binding energy per nucleon of light nuclei is smaller than that of nuclei with mass numbers near 70, and fusing those light nuclei together increases the average binding energy per nucleon, thus releasing energy. This process is known as fusion, and it is the source of energy of the sun and other stars. In the sun, the process used to generate energy fuses four protons. The conservation of charge requires that electrons be emitted in this process. If one could build a controlled fusion reactor, we would be able to generate energy by combining the very abundant hydrogen and/or deuterium found in water, and create helium, a very useful, yet environmentally harmless inert gas. No radioactive byproducts would be produced.

ELEMENTARY PARTICLES

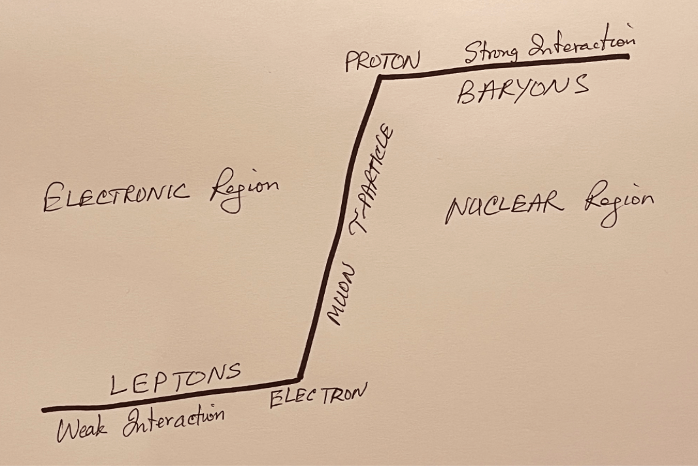

These are the new sub-atomic particles that we have been considering, such as, baryons, leptons and photons.

BARYONS

This is the class of particles that contain protons and neutrons.

KHTK NOTE: Baryons represent the very condensed substance in the nuclear region.

LEPTONS

This is the class of particles that contain the electron, positron and neutrino.

KHTK NOTE: Leptons represent the much less condensed substance in the electronic region.

ANTI-PARTICLE

Positrons were predicted by Dirac after he showed that the correct set of quantum wave equations that are consistent with relativity predicted the existence of an “antiparticle” for each particle. These antiparticles are nearly identical with their particles and have either the same or the opposite properties of their particle. Thus, a positron has the same mass as the electron, but the opposite charge. The properties of particles and antiparticles are always such that they can annihilate each other if they meet, with their entire rest masses being converted into energy (usually γ-rays), without violating any conservation law. Similarly, pairs of particle-antiparticle can be produced directly from the conversion of γ-ray energy into the pair (usually in the presence of some heavy object such as a nucleus) without violating any conservation laws. The γ-ray must, of course, have at least an energy equal to the combined rest mass energy of the created particles.

PHOTON

The photon is a particle that turns out to be its own antiparticle. This means that there is no distinction between particle and antiparticle photons, since both have the same charge (zero), rest mass (zero), baryon number (zero), spin (one), etc.

VIRTUAL PHOTONS

See ELECTROMAGNETIC INTERACTION. Since these photons are not free to travel away, they are called virtual photons to distinguish them from photons that carry energy through space. Thus, virtual photon can be considered the carrier of the electric and magnetic force between charged particles.

KHTK NOTE: Particles of very near consistencies maybe considered to be exchanging virtual photons because charge represents the gradient of consistency (degree of condensation) of the substance.

ELECTROMAGNETIC INTERACTIONElectromagnetic interaction is the interaction between the electrons and nucleus in an atom. These interactions can be described in terms of the “virtual” exchange of photons. By this we mean that the electromagnetic interaction between charged particles can be considered a consequence of a possible continuous creation of photons by one charge and absorption by the other charge.

ELECTRODYNAMICS

The full theory of these interactions with virtual photons is called quantum electrodynamics. The idea that one type of particle is the carrier of the force between other particles can be carried over to other forces as well. The electromagnetic force allows charged particles to exist in both bound states (electrons in an atom) or free states (electrons or protons moving through space).

MUON

Muons make up much of the cosmic radiation reaching the earth’s surface. A muon is an unstable subatomic particle that has spin ½, and a negative charge e, but with a mass around 200 times greater. But in other respects, it behaves essentially the same as an electron. It is sometimes called a heavy electron.

KHTK NOTE: The charge of “-1” means that the particle exists at the electron-nucleus interface. It represents the steep change in the consistency of substance.

STRONG INTERACTION

Strong interaction is the force that that holds nucleons together in the nucleus. In Strong interactions the decay proceeds very fast and they require the conservation of strangeness quantum number. The strong interaction can be considered as arising from the interchange of particles, called “gluons,” among quarks.

KHTK NOTE: Strong interaction represents the gradient of consistency of substance within the nucleus.

WEAK INTERACTION

Weak interaction is the interaction at short distances between subatomic particles called leptons mediated by the weak force. The weak interaction can be considered as arising from the virtual interchange of particles, called “vector bosons.” The weak interaction and the electromagnetic interaction have now been shown to be two aspects of the common “electroweak” interaction.

KHTK NOTE: Weak interaction represents the gradient of consistency of substance within the electron region.

TAU PARTICLE

The tau particle is similar to the electron and muon with a rest mass of 3490 times that of electron. The muons and the tau particle are unstable, and decay to electrons of smaller rest mass.

KHTK NOTE: The electron-muon-tau represent the suddenly increasing consistency of substance at the interface between the electronic and nuclear regions.

MESON

Meson is a subatomic particle which is intermediate in mass between an electron and a proton and transmits the strong interaction that binds nucleons together in the atomic nucleus. The least massive meson is a pion, which is 270 times heavier than the electron. The next massive meson is the kaon, which is 970 times heavier than the electron.

KHTK NOTE: Mesons glue together the baryons just like photons glue together the Leptons.

HADRON

Hadron is a subatomic particle of a type including the baryons and mesons, which can take part in the strong interaction.

QUARKS

The mesons and the baryons are viewed as composites of more fundamental particles, called quarks. We know of six different quarks, and all six have been detected indirectly by identifying the properties of mesons containing these quarks. All mesons are composed of one quark and one antiquark, and all baryons are composed of three quarks. The quarks interact by means of the strong interaction.

STRANGENESS

It is hard to understand why some particles, like the kaon, should have such a long half-life. After all, the kaon participates in the strong interaction, and can decay into pions that also participate in the strong interaction. There is a similar problem with the decay of a massive baryon called the lambda-particle, which is often created together with the kaon. The solution that was conceived is that these particles (as well as some other new particles) have a new quantum number, called “strangeness”, which must be conserved in an interaction involving nuclear forces (strong interaction). Strangeness is a new property that, like electric charge, baryon number and lepton number, can be both positive and negative. Strangeness is conserved in strong interactions but not in weak interactions. Decay through weak interactions have a relatively longer half-life. Conservation of strangeness introduces a new concept insofar as it is not an absolute conservation law. It is required for the strong interaction (and the electromagnetic interaction), but not for the weak interaction.

GLUONS

The particles that are being interchanged among quarks in strong interaction are called “gluons” since they are responsible for “gluing together” the quarks.

“COLOR” CHARGE

Each quark has a three valued index called “color” charge. The color charge is a quantity comparable to electric charge in electrodynamics, except that there are two types of electric charges and three types of color charges.

CHROMODYNAMICS

The theory of the strong interaction is called “chromodynamics” because the label “color” has been commonly used for this index. Neither quarks nor gluons have ever been seen alone. It is now believed that quarks can only exist in bound states so that one will never see a free quark. This is a consequence of the nature of the strong force provided by the gluons to the quarks.

STANDARD MODEL

Much of our present understanding of elementary particles and the world built out of them is explained by a comprehensive theory called the “Standard Model”. Even so, much more needs to be understood, such as the reason the fundamental particles have the rest masses that they do, and whether all the forces of nature can be understood to be different aspects of the same interaction.

KHTK NOTE: The rest masses are a measure of the consistency (degree of condensation) of energy particles. The interactions provide the continuity of substance that is condensing.

SOLID-STATE PHYSICS

Solid-state physics studies how the large-scale properties of solid materials result from their atomic-scale properties. Thus, solid-state physics forms a theoretical basis of materials science. Along with solid-state chemistry, it also has direct applications in the technology of transistors and semiconductors.

CRYSTAL

The simplest case of solid is the situation when the atoms are arranged in a fixed symmetric pattern which is repeated throughout the solid. Such a system is called a crystal. The results of analyzing this special case can be generalized to more complicated cases of solids with varying degrees of disorder (amorphous solids) and even to liquids. Together all the classes of material are called “condensed matter”.

ENERGY “BAND”

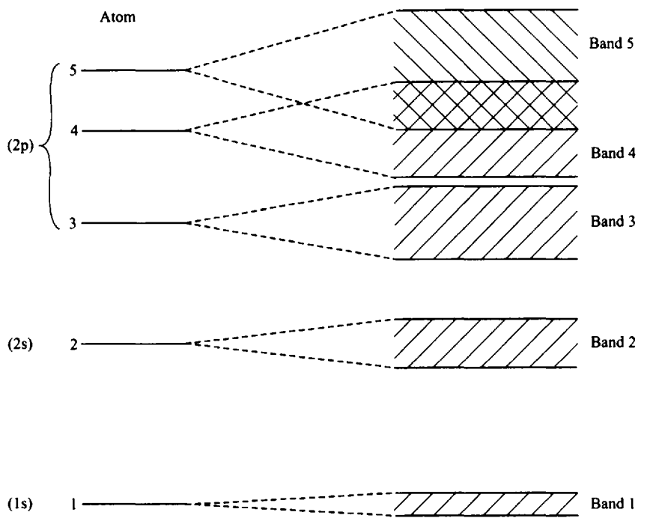

Two or more atoms that are far apart, have their own identical energy level structure. The electrons can be specified as being in a particular level of a particular atom. As one brings two atoms closer together, the wave functions begin to overlap, and the electron can no longer be considered as confined to only one atom. The result is that the individual levels of each of the two overlapping atoms become two closely spaced shared levels in each of which the electron is shared by the two atoms. As one adds more and more atoms, the electrons are shared by more atoms and the energy levels are best described as energy “bands.” Each band will have twice the number of electrons because of the overlapping of the two individual energy levels. Each energy level of the individual atoms become converted to a band able to accommodate two electrons per atom.

ENERGY GAP AND OVERLAP

There is an “energy gap” between some of the bands (see the figure above). This gap is large between bands 1 and 2 and is small between bands 3 and 4. At the energies within these gaps, there cannot be any electrons in the solid.

If there are an even number of electrons per atom, then one expects the highest band to be filled. However, if the bands overlap, as do bands 4 and 5 in the figure above, then the highest band containing electrons may not be filled even for an even number of electrons per atom.

This basic idea permits us to understand why certain solids act as insulators, while others act as conductors, and still others act as “semiconductors”.

ENERGY GAP AND OVERLAP

When one imposes a voltage between the ends of a wire, an electric field tries to accelerate the electrons in the material. The electrons that can move because of the imposed voltage are called “free” electrons.

CONDUCTION BAND

The energy band in which the “free” electrons move is called the conduction band. This is the case if the highest band containing electrons is not filled. The lower bands are called valence bands.

INSULATOR

If the upper valence band is filled, then there are no energy levels available for the highest energy electrons, and they will be unable to accelerate. We will then have an insulator.

SEMICONDUCTOR

If one can excite electrons from this filled valence band to the empty next higher band, that band would constitute a conduction band, and these excited electrons can move in an electric field. This type of excitation can occur if the temperature is sufficiently high that the thermal energy of the electrons allows them to jump to the conduction band. Materials such as these, with small energy gaps, are called semiconductors. They can change from insulators to conductors as the temperature increases.

HOLES

When an electron excites into the conduction band, we say that there is a positive “hole” created in the valence band and that the positive holes act just like positively charged particles and provide conduction in this band.

N-TYPE SEMICONDUCTOR

If one inserts atoms in the base semiconductor material, which have one extra electron, then there will be one more electron per impurity atom than is needed to fill the valence band. These added electrons can partially fill the conduction band and provides conduction appropriate to negative electrons. We call this material an n-type semiconductor.

P-TYPE SEMICONDUCTOR

If one inserts atoms in the base semiconductor material, which have one less electron, then there will be one state in the valence band that may be unfilled. This “hole” acts to provide conduction appropriate to a positive charge, and this material is called p-type semiconductor.

PHOTODETECTORS

It is also possible to excite electrons in an insulator or semiconductor to the conduction band by absorbing a photon. The incident photon that is absorbed will make it possible for the material to conduct electricity. This process is the basis for constructing photodetectors since the absorption of a photon is signaled by a change in the conductivity of the material.

.

The following definitions are from the philosophy of KHTK:

ATOMIC STRUCTURE

An electron cannot be treated as a point particle. The electron has a volume, and, within that volume, the energy substance of electron has the same consistency (degree of condensation) throughout. Multiple electrons come about due to different consistencies. The consistency of the electrons decreases with increasing distance from the nucleus. Therefore, multiple electrons appear as multiple shells around the nucleus of an atom. The quantum numbers simply specify the shells, and a fine structure of sub-shells within those shells.

ELECTRON SHELLS

Each energy level of the atom is associated with the consistency of electrons. The four quantum numbers seem to determine the shape of the electron shells within the atom. This shape is almost spherical close to the nucleus, but it flattens out to a disk-like shape away from the nucleus. This makes the shape of the atom look like the shape of a galaxy as it appears from its side.

CHARGE

The electron charge seems to be due to the sudden change in energy consistency at the electron-nucleus interface. The “attraction” is due to the CONTINUITY of the substance. Strong attraction corresponds to high gradient of continuity. Light attraction corresponds to light gradient of continuity. The “repulsion” occurs when the gradient of this consistency does not match. The electrons inside an atom are arranged by the gradient of their consistency and so they do not repel each other. Two negatively charged surfaces repel each other because there is a complete mismatch of the gradients of energy levels between them.

NUCLEAR SHELLS

Protons and neutrons are bound together in the nucleus because of the continuity of substance. They simply make different layers of the nucleus. These layers get more condensed as they get closer to the center. Protons have charge so they must form the surface of the nucleus to interface with the electrons. Neutrons fill the inside of the nucleus and are more condensed; so, they have slightly greater mass. As the nucleus grows, the number of neutrons get larger more rapidly than the number of protons because they fill the inside of the nucleus.

FUNDAMENTAL PARTICLES

There is a seemingly inexhaustible array of oddball particles, and the conservation laws begin to seem arbitrary and capricious. Most of these particles lie in the high gradient of consistency between the electron and proton at the electronic-nuclear interface. Such particles are unstable and decay into other particles. This indicates dynamic migration of substance across this interface.

.

Comments

Very nice summary. There are many angles here , about which I have no knowledge or only cursory knowledge.