Reference: Beginning Physics II

Chapter 15: INTERFERENCE. DIFFRACTION AND POLARIZATION

.

KEY WORD LIST

Phase, In Phase, Out of Phase, Interference, Constructive Interference, Destructive Interference, Interference versus Diffraction, Huygens’ Wavelets, Double Slit, Michelson Interferometer, Thin Film Interference, Non-Reflecting Coating, Wedge, Newton’s Rings, Diffraction, Single Slit, Single Hole, Diffraction Grating, Polarization Of Light, Absorption (Dichroism), Reflection, Birefringence, Scattering.

.

GLOSSARY

For details on the following concepts, please consult Chapter 15.

PHASE

Phase is the fraction of a period that a point completes after last passing through the reference, or zero, position. Phase is the ratio of elapsed time t to the period T, or t/T—and is equal to the ratio of the phase angle to the angle of the complete cycle, 360°, or 2π radians.

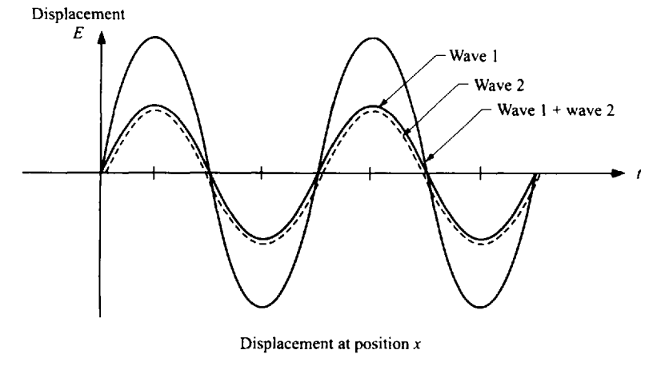

IN PHASE

When comparing the phases of two or more periodic motions, such as waves, the motions are said to be in phase when corresponding points reach maximum or minimum displacements simultaneously. The actual displacement is given at any time by the sum of these two displacements, using the principle of superposition.

The two waves are in phase not only if they take the same time to reach the new point, but also if one of them takes exactly one period longer than the other (or any integral multiple of the period longer).

OUT OF PHASE

If the crest of one and the trough of the other pass at the same time, the phase angles differ by 180°, or π radians, and the waves are said to be out of phase.

Here the time delay is of half a period, ∆t = T/2, or any half integral multiple of T, ∆t =

(m+ ½)T, between the two waves. The two waves are said to be “180° out of phase”, or “out of phase by π (radians)” or simply “out of phase.”

INTERFERENCE

Interference is the net effect of the combination of two or more waves moving on intersecting or coincident paths. The effect is that of the addition of the amplitudes of the individual waves at each point affected by more than one wave.

CONSTRUCTIVE INTERFERENCE

If two of the components are of the same frequency and phase, the wave amplitudes are reinforced, producing constructive interference.

∆t = mT or ∆l = mλ → constructive interference with m integer

DESTRUCTIVE INTERFERENCE

If the two waves are out of phase by 1/2 period (i.e., one is minimum when the other is maximum), the result is destructive interference, producing complete annulment if they are of equal amplitude.

∆t = (m +½) T or ∆l = (m +½) λ → destructive interference with m integer

INTERFERENCE VERSUS DIFFRACTION

If we have more than two waves then we must add together all the waves to get the resultant wave. This will clearly result in a more complicated calculation in practice, although the underlying principle is still the same. Typically, when we consider waves traveling through openings in different barriers arriving at a common point, we use the term interference to characterize the results of their addition. This often involves the addition of a relatively small number of waves. If we add together waves coming from different parts of a single aperture and arriving at a common point, we usually refer to the effect as diffraction, and the addition can involve, in principle, large numbers of waves. Nonetheless, the basic principle for diffraction is the same as for interference.

HUYGEN’S WAVELETS

The Huygens–Fresnel principle states that every point on a wavefront is itself the source of spherical wavelets, and the secondary wavelets emanating from different points mutually interfere. The sum of these spherical wavelets forms a new wavefront.

DOUBLE SLIT

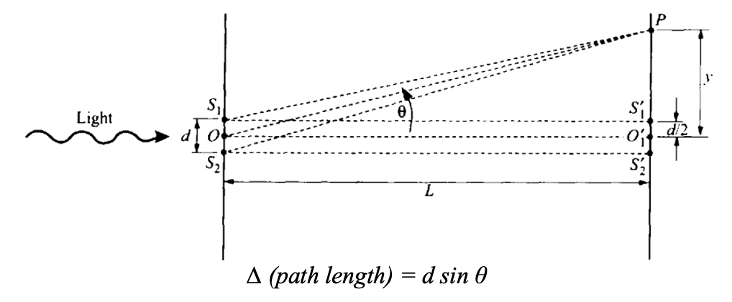

The double slit is an example of interference. From the geometry, the following result can be derived mathematically.

We can now determine the angles at which we have destructive and constructive interference by equating this difference in path length to the appropriate multiples of λ. The angle at which the first maximum occurs depends on λ/d. When λ/d is small, then sin θ is small, as is θ. If the ratio is not too small, one can see these interference effects. For wavelengths that are very short compared to the geometric dimensions of slits and apertures, there is little ability of the light to bend and there will be neither diffraction nor interference that is detectable. To see fringes, one needs this ratio to be much less than 1, but still not minuscule. One could use the double slit to measure the wavelength of some unknown radiation by measuring the angle at which interference occurs. In practice, one gets greater experimental accuracy if one uses a diffraction grating that contains thousands of slits rather than just two slits.

MICHELSON INTERFEROMETER

Here, light from a source, S, gets split and travels two different paths to reach the detector as shown. The criterion for constructive interference remains that the difference in path length, 2∆D, equals an integral multiple of the wavelength.

As we change the distance to one of the mirrors, the detector will alternately record a large intensity and zero intensity as the interferometer changes from constructive to destructive interference and back again. This can be used to measure very small distances accurately.

THIN FILM INTERFERENCE

The bright colors seen in an oil slick floating on water or in a sunlit soap bubble are caused by interference. The brightest colors are those that interfere constructively. This interference is between light reflected from different surfaces of a thin film; thus, the effect is known as thin film interference.

NON-REFLECTING COATING

One can coat a surface with a specific thickness of film to produce destructive interference for a particular wavelength. In that case there will be no reflection from the surface at that wavelength. This is then called a non-reflecting coating.

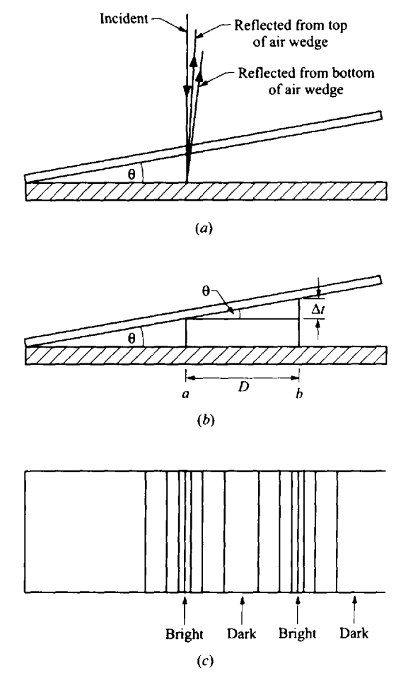

WEDGE

A wedgeconsistsof two smooth glass plates that make a very small angle with each other. The air between the plates forms a “thin film” whose thickness increases as we move away from the corner. For the wavelength of the incident light there will be a point along the bottom plate where the thickness of the film is just right to give constructive interference. The result is a series of “fringes,” or alternating bright and dark fringes along the glass plate.

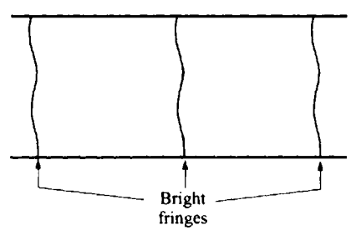

If the glass is not exactly smooth, the bright fringes will be somewhat distorted. The wavy line traces out points where the distance between the top and bottom plates is constant. This can be used to measure the smoothness of a plate. If the lines are distorted, one knows where one has to remove a small amount of glass and can grind the glass there to achieve better smoothness. Since these fringes are sensitive to distances of fractions of a wavelength, this can assure smoothness to that order of distance.

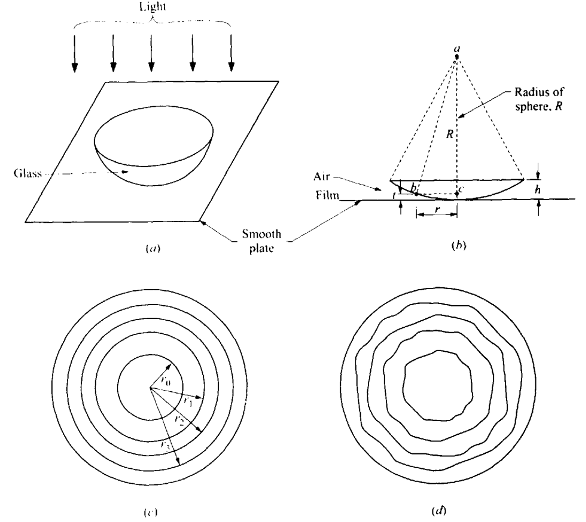

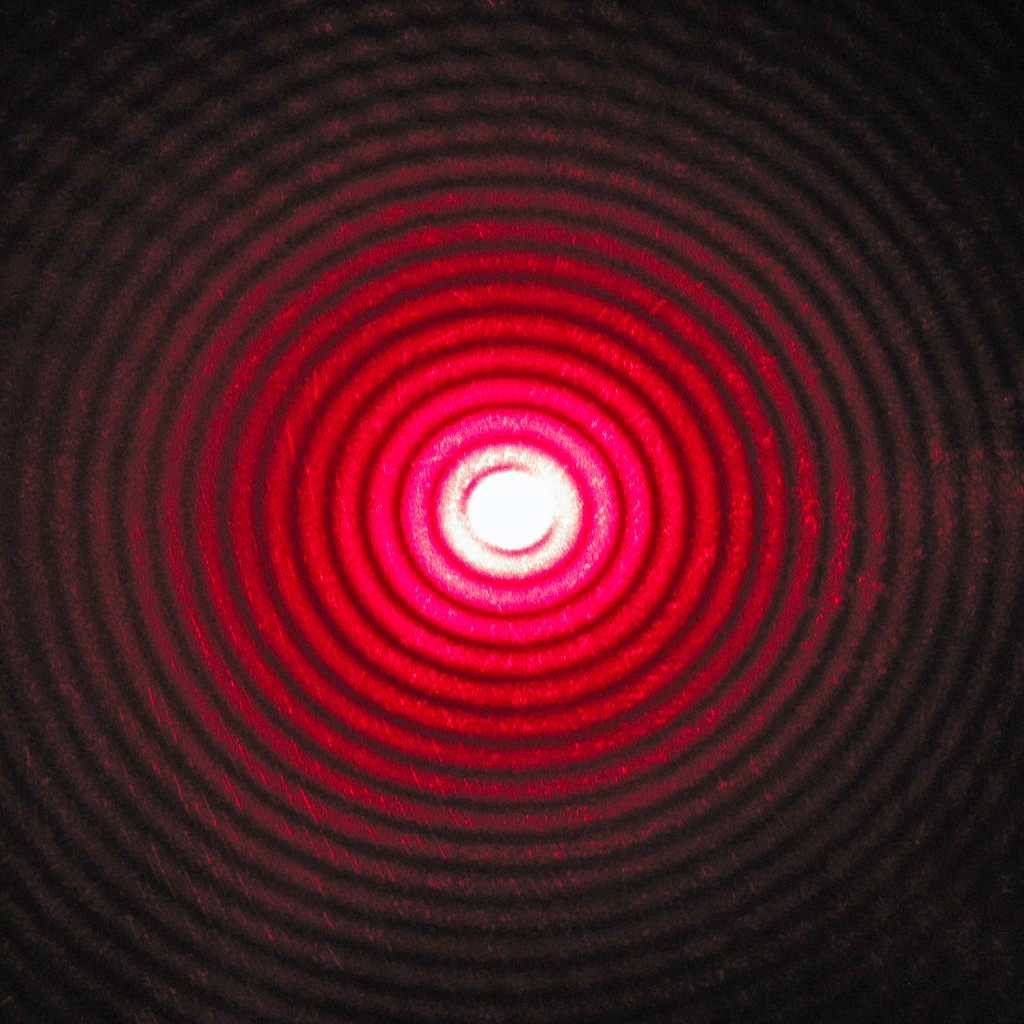

NEWTON’S RINGS

When a sector of a glass sphere is placed on a smooth glass plane, there is an air film between the lower surface of the sector and the plane. The height of this film increases as one moves out from the center. Points of equal height form circles around the center. Therefore, circular fringes appear because of the wedge principle above.

The circles seen are called Newton’s rings. This technique is used as standard procedure to test and adjust the smoothness and symmetry of spherical glass surfaces.

DIFFRACTION

Diffraction is the process by which a beam of light or other system of waves is spread out as a result of passing through a narrow aperture or across an edge, typically accompanied by interference between the wave forms produced.

SINGLE SLIT

For a single slit we get the following mathematical relationship.

w sin θ = mλ, m = 1, 2, 3 . . . (destructive interference)

The intensities at these maxima decrease as θ increases. The intensity at the center is far greater than the intensity at any of the secondary maxima. Additionally, the central maximum is wider than any of the other maxima, and it has a width of

δcent = 2Lλ/w

The secondary fringes have width half as wide.

δ = Lλ/w

The angle of diffraction (the angle for the first minimum) increases with λ/w. The wave spreads out into a central bright fringe between (this angle). As w gets smaller, approaching λ, the central bright fringe gets bigger, and the light spreads out more widely. We therefore see that one cannot consider the light as moving in a straight line if there are apertures comparable to the wavelength of the light.

SINGLE HOLE

For a small circular aperture, the light would bend into a larger circle, with the angle of diffraction increasing as the diameter, D, of the hole decreases. The result is a bright central circular area (called the Airy disk), in which most of the energy of the light is concentrated, with secondary rings at larger angles containing smaller amounts of light energy. A small object viewed through a circular aperture expands into a larger circle, with the angle for the edge of the Airy disk given by:

sin θ = 1.22(λ/D)

As (λ/D) becomes larger, the image size increases. If we view two neighboring tiny objects through the hole, we can no longer “resolve” them from each other. Thus, diffraction imposes a limit on our ability to resolve closely spaced objects as through telescope. For the best resolution, we must have large aperture D and/or small wavelength λ. In order to increase our resolving power we must use waves of shorter wavelength, such as ultraviolet light or X-rays, or “electron waves.” Furthermore, this is one of the reasons that telescopes are built with the largest practical diameter objective lens or mirror.

DIFFRACTION GRATING

When there are very many, closely spaced slits on a plate, we call the arrangement a “diffraction grating.” Gratings can easily have 10,000 lines per cm, giving a spacing of d = 10-6 m. The angles at which we get multiple slit maxima (the angle through which the light is “diffracted”), is given by:

d sin θ = mλ

The angle at which maxima occur clearly depends on the wavelength, and for multi-frequency light, for each value of m, there will be a spectrum of colors, from blue to red, as the angle θ increases. We can use this multiple slit arrangement to measure wavelengths very accurately, and to separate out different wavelengths in the source of light.

POLARIZATION OF LIGHT

The electric field lies in the plane perpendicular to the direction of motion. We call the direction of the electric field in this plane the direction of “polarization”. Most light that is produced by sources such as incandescent bulbs is unpolarized, meaning the electric field has no preferred direction. The simplest, and most common, case of polarization is one in which the electric field always points along one direction. This case is called linearly polarized light, or plane polarized light.

ABSORPTION (DICHROISM)

Dichroism is the property of some crystals and solutions of absorbing one of two plane-polarized components of transmitted light more strongly than the other. An example of such a material is a sheet of “polaroid”, which produces light polarized in one linear direction.

REFLECTION

Brewster’s angle is an angle of incidence at which light with a particular polarization is perfectly transmitted through a transparent dielectric surface, with no reflection. When unpolarized light is incident at this angle, the light that is reflected from the surface is therefore perfectly polarized.

BIREFRINGENCE

Birefringence is the phenomenon exhibited by certain materials in which an incident ray of light is split into two rays, called an ordinary ray and an extraordinary ray, which are plane-polarized in mutually orthogonal planes, or circular-polarized in opposite directions (left and right).

SCATTERING

Scattering offers another means of producing polarized light. In fact, the light from the sun scattered by the atmosphere (the light we see during the day if we don’t look at the sun), will be polarized, and we can selectively remove that light by using a polarizer that does not transmit that polarization.

.