Reference: Beginning Physics II

Chapter 12: ELECTROMAGNETIC WAVES

.

KEY WORD LIST

Displacement Current, Maxwell’s Equations, Gauss’ Law, Magnetic Fields, Faraday’s Law, Ampere’s Law, Electromagnetic Waves, Electromagnetic Spectrum, Electromagnetic Wave Equation, Energy And Momentum Flux, Poynting Vector, Radiation Pressure

.

GLOSSARY

For details on the following concepts, please consult Chapter 12.

DISPLACEMENT CURRENT

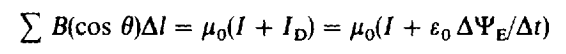

We know that the field within a parallel plate capacitor is uniform and is equal to E = q/ε0A, where q is the charge on the capacitor and A is the area of the capacitor. If the capacitor is being charged, then both q and E are changing, and we can write that ∆E/∆t = (∆q/∆t)/ε0A = ID/ε0A, where ID is the displacement current between the capacitor plates (compared to the conductor current in the wire).

Thus,

ID = ε0A(∆E/∆t) = ε0 (∆E A/∆t) = ε0 (∆ψ/∆t)

where ψ is the electric flux through the area.

MAXWELL’S EQUATIONS

These four equations are relationships between the electric and magnetic fields and their sources, charges and currents. The electric and magnetic fluxes are determined directly from the electric and magnetic fields and are not separate variables. Thus, these equations tell us how to calculate the electric and magnetic fields that are produced by charges, both at rest and moving. The particular form that we have used for these equations is not the most useful for actual calculations but is the easiest to understand conceptually. For purposes of calculations, these equations are expressed more formally in the language of the integral and differential calculus, which can then be solved for specific cases.

(1) GAUSS’ LAW

The electric fields can be established by free charges. All electric field lines start at positive charges and end on negative charges (lines can also go to infinity, such as those of an isolated point charge, where they are presumed to land on opposite charges at that distance). By convention the number of electric field lines per unit area, the electric flux density, at a given point is chosen equal to the magnitude of the electric field at that point. It then equals the electric field at every other point as well. Gauss’ law then relates the total charge within a closed surface to the net number of electric field lines that pass through the surface.

(2) MAGNETIC FIELDS

There are no magnetic monopoles that act as sources for a magnetic field. Therefore, magnetic fields do not have poles where they begin or end. All magnetic field lines must therefore close on themselves. This means that any magnetic field line that passes through a closed surface must necessarily pass through the surface again in the opposite direction, in order to close on itself. This means that the net total magnetic flux which passes through a surface is zero.

(3) FARADAY’S LAW

An electric field can also be produced by a changing magnetic flux.

(4) AMPERE’S LAW

The magnetic fields are created by currents, either conduction current or displacement current.

These four equations constitute Maxwell’s equations, which are the fundamental laws governing the existence of electric and magnetic fields, which are jointly called electromagnetic fields. Electric fields exert forces on any electrical charges, while magnetic fields exert forces on moving charges.

ELECTROMAGNETIC WAVES

Maxwell was able to show that there were solutions to these equations that corresponded to waves propagating in free space, i.e., in regions where there are no charges or currents. These waves, which he called electromagnetic waves (EM) had special properties, which could be derived from these equations.

In the case of electromagnetic waves the time varying quantity is not the displacement but rather the electric and magnetic fields at a point in space.

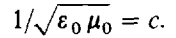

These waves are transverse, and their speed, in free space is equal to

For a wave traveling in the x direction, the electric and magnetic fields associated with this wave are in the y-z plane. These fields are also perpendicular to each other, and that their magnitudes are given by:

E = cB

It is useful to consider electromagnetic waves that are sinusoidal. This means that if we take a picture of the wave at any time, the disturbance will vary sinusoidally in space along the direction of propagation. Furthermore, at any position is space, the disturbance will vary sinusoidally in time.

The disturbance associated with an electromagnetic wave is the electric and magnetic field along the wave. Light consists of electromagnetic waves in a certain frequency range to which the eye is sensitive and can “see”.

ELECTROMAGNETIC SPECTRUM

Electromagnetic waves exist with wavelengths ranging from very small to very large (and corresponding frequencies from very large to very small). The various possible wavelength (and frequency) ranges constitute the electromagnetic spectrum. For small frequencies the wave is usually denoted by its frequency, and for short wavelength it is denoted by its wavelength.

All of these waves travel with a speed of c, all are transverse, and all carry perpendicular electric and magnetic fields with them.

ELECTROMAGNETIC WAVE EQUATION

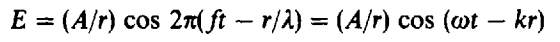

The equation for the disturbance of an electromagnetic sinusoidal plane wave, traveling in the + x direction, is given in terms of its disturbance (an electric field in the y direction) by

Here ω is the angular frequency of the wave, and k is the “wavenumber” of the wave and has units of m-1. E0 is the maximum value of the electric field and is thus the amplitude of the wave.

For spherical waves, since the area of a spherical surface is 4πr2, the intensity falls off as l/r2. The amplitude of the wave, A, is related to the intensity by I α A2, and therefore A falls off as l/r. The formula for the magnitude of E is given by

ENERGY AND MOMENTUM FLUX

The electric and magnetic fields contain energy (substance). The energy density is uE = ε0E2/2 for electric fields and uB = B2/2μ0 for magnetic fields. The electromagnetic energy of an electromagnetic wave is just the sum of the energies of its electric and magnetic fields. The maximum energy is located at those points where the fields are at their maxima, which occurs at the crests of these waves. But these crests move with time at a speed of c, and therefore the energy is transported in the direction that the wave travels at this speed. An electromagnetic wave, therefore, carries energy and momentum with it.

The average energy transported per unit area and time as the wave travels with speed c in the x direction is defined as the intensity:

POYNTING VECTOR

The Poynting vector S depicts the direction and rate of transfer of energy, that is power,due to electromagnetic fields in a region of space. Its magnitude is EB/μ0, and its direction is perpendicular to E and B, and obeying the right-hand rule.

Whenever energy moves in a certain direction, there is also a certain amount of momentum in that direction. This is because energy is substance.

RADIATION PRESSURE

One can use sunlight in space to not only supply power but to exert a force on a spacecraft. The force that is exerted on the surface can best be characterized by the force exerted per unit area, or pressure, P = F/A.

.