Reference: Einstein’s 1920 Book

Section XXVII (Part 2)

The Space-Time Continuum of the General Theory of Relativity Is not a Euclidean Continuum

Please see Section XXVII at the link above.

.

Summary

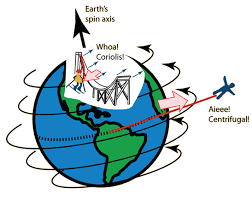

The space time continuum of the special theory can be regarded as four-dimensional Cartesian co-ordinates if we consider the velocity of light to be constant. For a rotating body of reference, a gravitational field is present; and, therefore, the velocity of light will depend on the coordinates. We cannot consider four-dimensional Cartesian co-ordinates in the general theory of relativity.

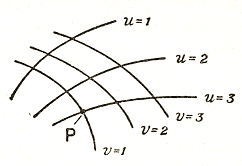

We refer the four-dimensional space-time continuum in an arbitrary manner to Gauss co-ordinates. In themselves these co-ordinates have no significance. A momentary existence of a material point at a location without duration will be represented by a single coordinate point. A permanent existence of a material point with motion shall then be represented by an infinitely large number of coordinate points as in a continuous line. Encounters among material points shall be represented by coincidences among coordinate points.

The motion of a material point relative to a body of reference shall be represented by encounters of that material point with particular points of the reference-body. This will take into account all kind of variations in both space and time in terms of flexibility, inertia or consistency.

All physical descriptions of space-time relationships can then be represented by coincidences among Gaussian coordinates of a body with a reference body. The Gaussian coordinates do not suffer the limitation of absolute rigidity of the Cartesian coordinates.

.

Final Comments

A body in uniform motion may not have acceleration, but it has a constant velocity. This constant velocity differs from body to body due to differences in their inherent structure. This inherent structure appears as the mass, inertia, rigidity or consistency of the body.

Light has near zero consistency and near infinite velocity; whereas, matter has near infinite consistency and extremely low range of velocities. By extrapolating between these data points, the special theory of relativity manages to come up with an approximate method to calculate the relative velocity in uniform motion for matter.

The general theory of relativity accounts for acceleration by relating instantaneous changes in consistency to changes in velocity throughout a continuum. Thus, it accounts for acceleration that manifests in the form of gravitational field.

.